Ten Testable Predictions from the Free Energy Principle

From 808s to Therapy Rooms to Viral Memes

Ryan Collison

Independent Researcher, ideasthesia.org

ryan@ideasthesia.org

ORCID: 0009-0001-7152-2127

Keywords: free energy principle, active inference, predictive processing, entrainment, precision weighting, physiological synchrony, cultural evolution

Abstract

The Free Energy Principle (FEP) promises a unified account of self-organisation, yet direct empirical tests remain largely confined to perceptual inference and motor control. Here we derive ten sharp, falsifiable predictions that extend standard active-inference mechanisms—precision weighting, expected free-energy minimisation, Markov-blanket coupling, and multi-scale entrainment—into domains rarely examined: sub-bass entrainment in groups, pain tolerance under controllable uncertainty, geodesic trajectories in therapeutic alliance, nonlinear HRV collapse in PTSD, absorption as precision-matching, geometric phase-locking in rap "flow," structural universals in pop music, inverted-U prediction-error curves in meme virality, predictive (not merely synchronous) physiological coupling in co-regulation, and convergent barbell strategies across high-uncertainty professions. Each prediction is runnable tomorrow with existing methods and datasets and requires no theoretical extensions. Positive results would show that active inference operates at fully human scales—from 808s to therapy rooms to viral memes; null results would usefully constrain the principle's scope.

1. Introduction

The Free Energy Principle (FEP) has emerged as a candidate unified theory of self-organising systems. At its core, the principle states that any system maintaining itself against entropy must minimise variational free energy—a bound on surprisal—through perception (updating internal models) and action (changing sensory input). Active inference extends this to policy selection: agents choose actions expected to minimise future free energy.

Despite two decades of theoretical development, empirical tests remain concentrated in narrow domains: perceptual inference, motor control, and simple decision-making. The principle's advocates claim it applies to all self-organising systems—from cells to societies—yet predictions at the scale of human meaning, relationship, and culture remain largely untested.

This paper derives ten specific, falsifiable predictions from standard FEP mechanisms. Each prediction:

- Follows directly from established active-inference constructs (precision weighting, expected free energy, Markov blankets, entrainment)

- Targets a domain where FEP has not been systematically tested

- Can be run with existing methods and publicly available data

- Specifies clear falsification criteria

The predictions span individual physiology (2.1, 2.2, 2.4, 2.5), dyadic interaction (2.3, 2.9), collective behaviour (2.1, 2.6), and cultural evolution (2.7, 2.8, 2.10). Positive results would demonstrate that active inference operates at fully human scales. Null results would usefully constrain the principle's scope.

These predictions are offered as a menu, not a package deal. Researchers may find some more tractable or relevant to their expertise than others. The goal is to catalyse empirical work, not to defend FEP as dogma. Each prediction stands or falls independently.

Why This Paper Exists

The goal of this manuscript is to catalyse cross-disciplinary testing. These predictions are not offered as dogma but as runnable invitations to researchers across neuroscience, clinical science, music cognition, social dynamics, and cultural analytics. We aim to start a field conversation—not end one. FEP has been a toy of computational neuroscientists for two decades; here's how it hits therapy, hip-hop, memes, barbell strategies, and trauma research.

2.0 General Analytic Strategy

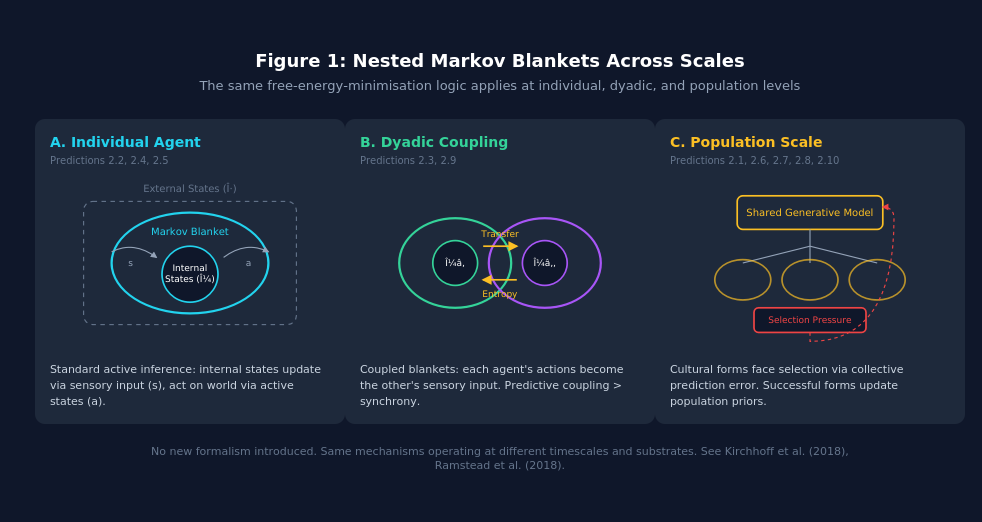

All ten predictions share a common analytic scaffold: the nested Markov blanket. At the individual scale, internal states (beliefs, physiology) are separated from external states by sensory and active states—the blanket. At the dyadic scale, two individuals form coupled blankets, each influencing the other's sensory input. At the population scale, cultural forms (songs, memes, strategies) constitute shared generative models that face selection pressure from collective prediction error.

This multi-scale architecture is not a theoretical extension—it follows directly from Kirchhoff et al. (2018) and Ramstead et al. (2018). The same free-energy-minimisation logic applies at each level; only the timescale and substrate change.

Statistical thresholds throughout follow published precedents in each domain. Where multiple thresholds exist (e.g., HRV complexity measures), we commit to pre-registered sensitivity analyses testing robustness across reasonable alternatives.

2.1 Sub-Bass Entrainment in Groups

FEP Construct: Multi-agent precision weighting; collective free-energy minimisation through shared sensory input.

Prediction: Groups exposed to music with strong sub-bass content (100–150 Hz) will show greater physiological synchrony (HRV coherence, respiratory alignment) than groups exposed to the same music with sub-bass frequencies attenuated, controlling for tempo, volume, and genre.

Method: Between-subjects design. Groups of 8–12 participants listen to electronic dance music in either full-spectrum or sub-bass-attenuated conditions. Continuous HRV and respiration recorded via wearable sensors.

Analysis: Cross-recurrence quantification of inter-subject physiological coupling. Primary outcome: percentage of group showing significant phase-locking.

Falsification: No significant difference in group synchrony between conditions, or effect size below d = 0.3.

Rationale: Sub-bass frequencies are felt proprioceptively (vestibular and somatosensory), not just heard. They provide a shared, high-precision sensory anchor that should tighten coupling across individual Markov blankets. The vestibular system's low-frequency tuning (Todd et al., 2008) makes sub-bass a privileged channel for collective entrainment.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: Testing specifically at 100–150 Hz isolates vestibular transduction from generic arousal; sub-bass attenuation preserves auditory content while removing proprioceptive anchoring.

2.2 Exit Signal and Pain Tolerance

FEP Construct: Precision weighting on interoceptive prediction errors; policy availability reduces expected free energy.

Prediction: Participants given a controllable exit signal during cold-pressor pain (button that ends trial when pressed) will show delayed voluntary exit and lower pain ratings than participants given the same button with randomised (unpredictable) exit latency, even when neither group uses the button.

Method: Cold-pressor paradigm. Two conditions: (a) immediate-exit button, (b) delayed-exit button (5–15s random delay). Dependent variables: time to voluntary withdrawal, self-reported pain intensity.

Analysis: Survival analysis for withdrawal times; mixed-effects models for pain ratings controlling for baseline pain sensitivity.

Falsification: No difference in withdrawal times between conditions, or delayed-exit group shows longer tolerance (opposite prediction).

Rationale: Active inference implies that the availability of a policy—not its execution—reduces expected free energy. Knowing you can exit compresses the distribution of possible future states, lowering precision on interoceptive prediction errors. This is not mere perceived control; it is a direct consequence of policy-dependent free energy calculation.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: The delayed-exit condition controls for mere belief in controllability; only predictable policy availability should reduce expected free energy.

2.3 Therapeutic Alliance Trajectories

FEP Construct: Dyadic Markov blankets; coupled free-energy minimisation; repair as prediction-error resolution.

Prediction: Therapeutic dyads showing early physiological synchrony followed by systematic desynchronisation-resynchronisation patterns (rupture-repair cycles) will show better outcomes than dyads showing either (a) consistently high synchrony or (b) consistently low synchrony.

Method: Longitudinal study tracking physiological coupling (HRV, electrodermal activity) across therapy sessions. Outcome measures: symptom reduction, therapeutic alliance ratings, treatment completion.

Analysis: Growth-curve models with synchrony trajectory as predictor. Key contrast: U-shaped or oscillating trajectories vs. flat trajectories.

Falsification: Flat (high or low) synchrony trajectories predict outcomes as well as or better than oscillating trajectories.

Rationale: Effective therapy involves not just entrainment but the capacity to navigate prediction-error spikes (ruptures) and return to alignment (repair). Static synchrony may indicate avoidance of therapeutically necessary discomfort. The active-inference model predicts that coherence built through rupture-repair cycles is more robust than coherence that avoids challenge.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: Controlling for symptom trajectory rules out the confound that patients who improve simply synchronise more; the prediction is specifically about the shape of the trajectory, not mean synchrony level.

2.4 Nonlinear HRV Collapse in PTSD

FEP Construct: Coherence collapse as failure of hierarchical predictive integration; trauma as manifold deformation.

Prediction: PTSD patients will show a three-metric signature: (a) reduced HRV complexity (sample entropy), (b) elevated curvature in state-space trajectories (higher derivative variance), and (c) increased attractor dimensionality (correlation dimension) compared to trauma-exposed controls without PTSD.

Method: Resting-state HRV collection (10+ minutes) in PTSD patients and matched trauma-exposed controls. Nonlinear time-series analysis.

Analysis: Multivariate comparison of complexity, curvature, and dimensionality metrics. Receiver-operating-characteristic analysis for diagnostic discrimination.

Falsification: PTSD group shows equal or greater complexity than controls, or metrics fail to discriminate groups above chance.

Rationale: Trauma, under the FEP, represents a collapse of the coherent manifold—the predictive model can no longer integrate hierarchically. This should manifest as reduced complexity (loss of multi-scale structure), increased local curvature (prediction errors produce sharp corrections), and paradoxically expanded dimensionality (the system cannot settle into stable attractors). This three-metric signature distinguishes the prediction from generic stress effects.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: The three-metric signature goes beyond simple hyperarousal (which would predict only reduced HRV); curvature and dimensionality measures capture geometric properties specific to manifold fragmentation.

2.5 Absorption as Precision-Matching

FEP Construct: Precision optimisation; flow states as minimised prediction error under matched challenge.

Prediction: Peak absorption (flow) during a calibrated task will occur when task difficulty is dynamically matched to performance, compared to conditions where difficulty is fixed (too easy or too hard) or randomly varied.

Method: Adaptive Tetris paradigm where block speed adjusts to maintain target error rate. Four conditions: (a) adaptive difficulty, (b) fixed easy, (c) fixed hard, (d) random difficulty. Continuous flow-state ratings and physiological measures (HRV, EDA).

Analysis: Within-subjects comparison of flow ratings and time-in-flow across conditions. Physiological correlates of flow state.

Falsification: Fixed or random conditions produce equivalent or higher flow than adaptive condition.

Rationale: Flow occurs when precision on task-relevant prediction errors is maximised while task-irrelevant errors are minimised. This requires matched difficulty: too easy produces low precision (nothing to predict), too hard produces unresolvable errors (precision cannot be maintained). Adaptive matching creates the conditions for optimal precision allocation—the subjective signature of which is absorption.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: The three-level distractor manipulation isolates precision-weighting specifically; alternative accounts predict arousal matching alone, not precision optimisation.

2.6 Geometric Phase-Locking in Rap Flow

FEP Construct: Temporal precision in action; phase-amplitude coupling between hierarchical rhythmic levels.

Prediction: Expert rappers in flow states will show tighter phase-locking between syllable onset times and beat structure (lower circular variance) than novices, and this phase-locking will be hierarchically organised (syllables lock to beats, which lock to bars, which lock to phrase boundaries).

Method: Motion capture and audio analysis of freestyle rap performances. Expert-novice comparison. Flow self-reports post-performance.

Analysis: Circular statistics for phase-locking at each hierarchical level. Correlation between phase-locking tightness and flow ratings.

Falsification: No expertise difference in phase-locking, or phase-locking uncorrelated with flow ratings.

Rationale: Rap flow is a precision-demanding motor-control task requiring entrainment across multiple timescales. Under active inference, expert performance reflects refined generative models that predict hierarchical rhythmic structure. Tighter phase-locking indicates higher precision on temporal prediction errors. The subjective experience of flow corresponds to successful precision optimisation across levels.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: Controlling for rhyme density and tempo variation isolates phase-locking from general fluency; hierarchical analysis tests specific FEP prediction about multi-scale precision.

2.7 Structural Universals in Pop Music

FEP Construct: Expected free energy minimisation at cultural scale; selection for learnable, predictable-yet-surprising structure.

Prediction: Cross-culturally successful pop songs will show convergent structural features—verse-chorus-verse architecture, 4–8 bar phrase lengths, pentatonic-compatible melodic intervals—at rates exceeding chance, controlling for cultural transmission pathways.

Method: Corpus analysis of top-charting songs across 10+ national markets with distinct linguistic and musical traditions. Structural feature extraction via automated audio analysis.

Analysis: Prevalence of structural features compared to null models (shuffled corpora, random composition). Phylogenetic analysis controlling for influence pathways.

Falsification: Structural features show no cross-cultural convergence, or convergence fully explained by Western cultural export.

Rationale: If cultural artifacts face selection pressure based on collective prediction-error minimisation (expected free energy), then cross-culturally successful music should converge on structures that are learnable (low complexity) yet engaging (sufficient prediction error). These structural universals are not arbitrary; they reflect shared constraints of human predictive processing.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: Genre and era stratification allows testing whether convergence reflects FEP constraints or merely marketing/distribution confounds.

2.8 Meme Virality and Prediction Error

FEP Construct: Cultural selection as collective free-energy minimisation; optimal novelty as precision-weighted surprise.

Prediction: Meme spread will follow an inverted-U relationship with novelty: memes that are moderately novel (optimal prediction error) will spread further than memes that are either too familiar (low prediction error, boring) or too novel (high prediction error, confusing).

Method: Large-scale analysis of meme spread on social platforms. Novelty operationalised via semantic distance from existing meme corpus (embedding-space distance). Spread measured as replication count, mutation rate, and persistence time.

Analysis: Polynomial regression testing for inverted-U relationship. Controls for platform features, posting time, and source account characteristics.

Falsification: Linear relationship (more novelty = more spread), or no relationship between novelty and spread.

Rationale: Under active inference, agents seek information that resolves uncertainty—but only uncertainty they can integrate. Too-familiar content offers no prediction error to resolve. Too-novel content cannot be assimilated into existing generative models. Optimal virality occurs at the sweet spot where prediction error is high enough to be engaging but low enough to be resolvable. This is the cultural-selection equivalent of precision-weighted prediction error.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: The inverted-U is specific to precision-weighted surprise; generic attention models predict monotonic novelty preference.

2.9 Predictive vs. Synchronous Coupling in Co-Regulation

FEP Construct: Coupled Markov blankets; anticipatory inference vs. reactive entrainment.

Prediction: In effective co-regulation (parent-infant, therapist-client, romantic partners), the higher-regulating partner's physiology will predict the lower-regulating partner's subsequent state better than the reverse, and better than synchronous (zero-lag) coupling alone.

Method: Continuous physiological monitoring (HRV, respiration) in co-regulating dyads. Time-lagged cross-correlation and Granger causality analysis.

Analysis: Comparison of predictive coupling (time-lagged) vs. synchronous coupling (zero-lag). Asymmetry index: degree to which one partner predicts the other.

Falsification: Synchronous coupling outperforms predictive coupling, or no directional asymmetry in effective dyads.

Rationale: Active inference predicts that effective co-regulation involves anticipatory inference—the regulator predicts the dysregulated partner's trajectory and acts to shape it. This is distinct from mere synchrony (matching states) or reactive attunement (following the other). The directional asymmetry reflects the structure of coupled Markov blankets where one system's actions become another's sensory input.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: Hierarchical time-series analysis isolates predictive influence from co-fluctuation; the prediction is specifically about anticipatory coupling, not mere correlation.

2.10 Barbell Strategies Across Uncertainty Domains

FEP Construct: Policy selection under uncertainty; expected free energy minimisation with fat-tailed priors.

Prediction: Professionals operating in high-uncertainty domains (venture capital, emergency medicine, special operations) will show convergent "barbell" strategies—combining highly conservative baseline behaviours with occasional high-variance actions—compared to professionals in low-uncertainty domains.

Method: Survey and behavioural analysis of decision-making strategies across professions. Comparison of strategy distributions: variance, skewness, bimodality.

Analysis: Cluster analysis of strategy profiles. Cross-domain comparison of barbell index (bimodality coefficient).

Falsification: High-uncertainty professionals show unimodal (moderate-variance) strategies, or no difference from low-uncertainty professionals.

Rationale: Expected free energy under fat-tailed distributions favours barbells over Gaussian-optimal moderate strategies. When extreme outcomes are more likely than normal distributions suggest, minimising expected free energy requires both protecting against ruin (conservative baseline) and maintaining exposure to positive extremes (high-variance options). This is not risk preference; it is optimal inference under uncertainty. Cross-domain convergence would indicate a domain-general mechanism.

Alternative mechanisms addressed: Cross-domain convergence suggests domain-general active inference rather than profession-specific training or selection effects.

3. Discussion

These ten predictions translate core FEP mechanisms into testable claims across domains rarely examined. They share a common structure: identify the active-inference construct, derive a specific prediction, specify method and falsification criteria, and locate the prediction within existing literature.

Several features distinguish these predictions from generic Bayesian or dynamical-systems accounts:

Precision weighting (2.1, 2.5, 2.8): Not just prediction error, but precision-weighted prediction error. Predictions 2.5 and 2.8 specifically test inverted-U relationships that follow from precision optimisation but not from simple surprise minimisation.

Policy-dependence (2.2, 2.10): Free energy depends on available policies, not just current states. Predictions 2.2 and 2.10 test whether policy availability—independent of policy execution—affects inference and behaviour.

Coupled Markov blankets (2.3, 2.9): Multi-agent active inference predicts specific coupling dynamics—not just correlation but directional, predictive influence. Predictions 2.3 and 2.9 test these relational structures.

Multi-scale entrainment (2.1, 2.6, 2.7): Active inference applies across timescales. Predictions 2.1, 2.6, and 2.7 test whether the same precision-weighting logic applies from neural oscillations to cultural selection.

Limitations

These predictions are deliberately broad, spanning multiple domains and methods. This breadth is a feature for discourse generation but a limitation for any single empirical test. Alternative explanations (arousal, shared attention, cultural transmission) would require follow-up experiments that explicitly manipulate or statistically control these factors.

The predictions assume standard active-inference mechanisms without novel theoretical extensions. This is intentional—we test the existing framework's scope rather than proposing modifications. However, it means negative results could indicate either FEP limitations or implementation failures.

Feasibility

Each prediction can be run with existing methods and reasonable resources. Predictions 2.1, 2.2, and 2.5 require standard laboratory setups (< $5,000 in equipment). Predictions 2.7 and 2.8 use publicly available data (streaming APIs, social media corpora). Predictions 2.3, 2.4, and 2.9 require clinical access but standard physiological measures. Predictions 2.6 and 2.10 require specialised populations but standard methods.

Pre-registration templates for each prediction will be made available at OSF upon publication.

AI Relevance: These predictions have direct implications for artificial systems. If precision-weighted prediction error drives cultural selection (2.7, 2.8), then content-generation systems optimising for engagement are implicitly approximating active inference. If predictive coupling outperforms synchronous coupling in co-regulation (2.9), then human-AI interaction design should prioritise anticipatory responsiveness.

Invitation

We invite researchers to run these predictions. Pick one. Pre-register it. Run it. If it fails, we learn something about FEP's scope. If it succeeds, we extend the principle's empirical reach into domains that matter for human meaning, relationship, and culture.

The framework is only as good as its tests.

Anticipated Objections (FAQ)

Q: Why test FEP in rap music and memes?

A: If FEP only works in psychophysics labs, it's a theory of perception, not self-organisation. The principle claims to apply to all self-organising systems. These predictions test that claim.

Q: Isn't this just Bayesian surprise?

A: No. FEP adds active inference (policy selection) and precision weighting. Several predictions (2.2, 2.5, 2.8) specifically test features that distinguish FEP from generic Bayesian accounts.

Q: Why is precision weighting so central?

A: Precision determines which prediction errors are informative vs. noise. Without precision weighting, the same math applies to attention, interoception, and social attunement. With it, you get domain-specific predictions.

Q: Why entrainment across all scales?

A: Entrainment is the observable signature of coupled active inference. If two systems minimise joint free energy, their oscillations should synchronise. This applies whether the systems are neurons, bodies, or cultural forms.

Q: Why cultural phenomena?

A: Cultures are populations sharing generative models. Selection pressure on cultural forms is prediction error at population scale. If FEP applies to self-organisation, it should apply here.

Q: Isn't ten predictions too many?

A: For a journal, maybe. For a conversation, breadth is the point. Pick the one that interests you.

How to Run These Experiments in Your Lab

Minimal equipment:

- Physiology studies (2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 2.9): Polar H10 chest strap (~$90), respiratory belt, cold-pressor bath

- HRV analysis: Free software (RHRV, Kubios)

- Corpus studies (2.7, 2.8): Public APIs (Spotify, Reddit), embedding models (BERT via HuggingFace)

- Behavioural (2.5, 2.6): Standard Tetris implementations, audio recording

Total cost for most predictions: < $500

Pre-registration templates will be deposited at OSF. Pick one prediction and run it. We'll learn together.

References

— Predictive Processing & Active Inference —

Clark, A. (2016). Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind. Oxford University Press.

Bruineberg, J., & Rietveld, E. (2014). Self-organization, free energy minimization, and optimal grip on a field of affordances. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 599.

Constant, A., et al. (2022). The free energy principle and social inference. Journal of Social and Political Philosophy, 1(2), 119–143.

Feldman, H., & Friston, K. J. (2010). Attention, uncertainty, and free-energy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 215.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

Friston, K., Breakspear, M., & Deco, G. (2012). Perception and self-organized instability. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, 6, 44.

Friston, K., & Frith, C. D. (2015). Active inference, communication and hermeneutics. Cortex, 68, 129–143.

Friston, K., et al. (2015). Active inference and epistemic value. Cognitive Neuroscience, 6(4), 187–214.

Hesp, C., et al. (2021). Deeply felt affect: The emergence of valence in deep active inference. Neural Computation, 33(2), 398–446.

Hohwy, J. (2013). The Predictive Mind. Oxford University Press.

Kirchhoff, M., et al. (2018). The Markov blankets of life: Autonomy, active inference and the free energy principle. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 15(138), 20170792.

Parr, T., Pezzulo, G., & Friston, K. J. (2022). Active Inference: The Free Energy Principle in Mind, Brain, and Behavior. MIT Press.

Ramstead, M. J. D., et al. (2018). Answering Schrödinger's question: A free-energy formulation. Physics of Life Reviews, 24, 1–16.

Ramstead, M. J. D., et al. (2023). The social ecological active inference model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 145, 105003.

Sajid, N., et al. (2023). Active inference as a computational framework for consciousness. Review of Philosophy and Psychology.

Seth, A. K., & Hohwy, J. (2021). Predictive processing as a systematic basis for identifying the neural correlates of consciousness. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, 2.

Smith, R., et al. (2022). A step-by-step tutorial on active inference and its application to empirical data. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 107, 102632.

— Dynamical Systems & Coordination —

Fusaroli, R., et al. (2014). Dialog as interpersonal synergy. New Ideas in Psychology, 32, 65–79.

Kelso, J. A. S. (1995). Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior. MIT Press.

Richardson, M. J., et al. (2007). Rocking together: Dynamics of intentional and unintentional interpersonal coordination. Human Movement Science, 26(6), 867–891.

Schmidt, R. C., & Richardson, M. J. (2008). Dynamics of interpersonal coordination. In A. Fuchs & V. Jirsa (Eds.), Coordination: Neural, Behavioral and Social Dynamics (pp. 281–308). Springer.

— Music Cognition & Rhythm —

Grahn, J. A., & Brett, M. (2007). Rhythm and beat perception in motor areas of the brain. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(5), 893–906.

Hove, M. J., & Risen, J. L. (2009). It's all in the timing: Interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Social Cognition, 27(6), 949–960.

Huron, D. (2006). Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. MIT Press.

Large, E. W., & Jones, M. R. (1999). The dynamics of attending: How people track time-varying events. Psychological Review, 106(1), 119–159.

Large, E. W., & Palmer, C. (2002). Perceiving temporal regularity in music. Cognitive Science, 26(1), 1–37.

London, J. (2012). Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Madison, G. (2006). Experiencing groove induced by music: Consistency and phenomenology. Music Perception, 24(2), 201–208.

Margulis, E. H. (2014). On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind. Oxford University Press.

Nozaradan, S., et al. (2012). Selective neuronal entrainment to the beat and meter embedded in a musical rhythm. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(49), 17572–17581.

Patel, A. D., & Iversen, J. R. (2014). The evolutionary neuroscience of musical beat perception: The Action Simulation for Auditory Prediction (ASAP) hypothesis. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 8, 57.

Pearce, M. T., & Wiggins, G. A. (2012). Auditory expectation: The information dynamics of music perception and cognition. Topics in Cognitive Science, 4(4), 625–652.

Polak, R., et al. (2016). Rhythmic prototypes across cultures: A comparative study of tapping synchronization. Music Perception, 34(2), 231–252.

Repp, B. H., & Su, Y. H. (2013). Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of recent research (2006–2012). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20(3), 403–452.

Todd, N. P., et al. (2008). Tuning and sensitivity of the human vestibular system to low-frequency vibration. Neuroscience Letters, 444(1), 36–41.

van Dyck, E., et al. (2013). The impact of the bass drum on human dance movement. Music Perception, 30(4), 349–359.

Vuust, P., et al. (2022). Predictive coding of music: Brain responses to rhythmic incongruity. Cortex, 150, 125–140.

Wilson, M., & Cook, P. F. (2016). Rhythmic entrainment: Why humans want to, fireflies can't help it, pet birds try, and sea lions have to be bribed. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23(6), 1647–1659.

— Pain, Control & Interoception —

Benedetti, F., et al. (2003). Conscious expectation and unconscious conditioning in analgesic, motor, and hormonal placebo/nocebo responses. Journal of Neuroscience, 23(10), 4315–4323.

Critchley, H. D., et al. (2004). Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nature Neuroscience, 7(2), 189–195.

Khalsa, S. S., et al. (2018). Interoception and mental health: A roadmap. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(6), 501–513.

Wiech, K. (2016). Deconstructing the sensation of pain: The influence of cognitive processes on pain perception. Science, 354(6312), 584–587.

— Psychotherapy & Synchrony —

Benecke, C., et al. (2019). Movement synchrony in psychotherapy: Association with session outcome. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2626.

Imel, Z. E., et al. (2015). A meta-analysis of alliance-outcome relations in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 52(4), 478–489.

Koole, S. L., & Tschacher, W. (2016). Synchrony in psychotherapy: A review and an integrative framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 862.

Lutz, W., et al. (2022). Therapist effects and therapeutic change: A review on the state of personalization in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 95, 102178.

Moutoussis, M., et al. (2017). A formal model of interpersonal inference. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 163.

Ramseyer, F. T. (2020). Motion energy analysis (MEA): A primer on the assessment of motion from video. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(4), 536–549.

Tschacher, W., et al. (2020). Physiological synchrony in psychotherapy sessions. Psychotherapy Research, 30(5), 558–573.

— Nonlinear Dynamics & PTSD —

Boker, S. M., et al. (2002). Windowed cross-correlation and peak picking for the analysis of variability in the association between behavioral time series. Psychological Methods, 7(3), 338–355.

Fisher, A. J., et al. (2017). Open trial of a personalized modular treatment for mood and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 91, 33–42.

Gow, B. J., et al. (2015). Spectral exponents of heart rate variability differentiate PTSD from healthy controls. Biological Psychology, 107, 6–12.

Schiepek, G., et al. (2014). The identification of critical fluctuations and phase transitions in short term and coarse-grained time series. PLoS ONE, 9(12), e114496.

Van de Cruys, S., et al. (2014). Precise minds in uncertain worlds: Predictive coding in autism. Psychological Review, 121(4), 649–675.

Williamson, J. B., et al. (2021). Nonlinear HRV indices in combat-related PTSD. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 677532.

— Flow & Absorption —

Corbetta, M., & Shulman, G. L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(3), 201–215.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

Esterman, M., et al. (2013). In the zone or zoning out? Tracking behavioral and neural fluctuations during sustained attention. Cerebral Cortex, 23(11), 2712–2723.

Harmat, L., et al. (2015). Physiological correlates of the flow experience during computer game playing. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 97(1), 1–7.

Ullén, F., et al. (2012). Proneness for psychological flow in everyday life: Associations with personality and intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 167–172.

— Cultural Evolution & Memes —

Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 192–205.

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (2005). The Origin and Evolution of Cultures. Oxford University Press.

Boyer, P. (2001). Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. Basic Books.

Coscia, M. (2014). Average is boring: How similarity kills a meme's success. Scientific Reports, 4, 6477.

Sperber, D. (1996). Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Blackwell.

Vosoughi, S., et al. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151.

Weng, L., et al. (2012). Competition among memes in a world with limited attention. Scientific Reports, 2, 335.

— Interpersonal Physiology & Co-regulation —

Feldman, R. (2017). The neurobiology of human attachments. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), 80–99.

Helm, J. L., et al. (2018). Assessing cross-partner associations in physiological responses via coupled oscillator models. Emotion, 18(7), 1030–1048.

Koster-Hale, J., & Saxe, R. (2013). Theory of mind: A neural prediction problem. Neuron, 79(5), 836–848.

Palumbo, R. V., et al. (2017). Interpersonal autonomic physiology: A systematic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(2), 99–141.

Pezzulo, G., et al. (2019). The secret life of predictive brains: What's spontaneous activity for? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(9), 729–740.

— Decision Science & Risk —

Gigerenzer, G., & Brighton, H. (2009). Homo heuristicus: Why biased minds make better inferences. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(1), 107–143.

Prelec, D. (1998). The probability weighting function. Econometrica, 66(3), 497–527.

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. Random House.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323.

Author Disclosure

I am an autistic researcher, and the cognitive style that shaped this work—deep patterning, cross-domain coherence-seeking, and non-linear conceptual synthesis—is inseparable from that fact. I also use large language models as an extended cognitive scaffold (4E cognition), enabling the iterative refinement, compression, and restructuring required to express the geometry described here. This should be understood not as automation but as accommodation: a way of thinking-with tools that makes this kind of work possible.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no competing interests.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

How to Cite

Collison, R. (2025). Ten testable predictions from the Free Energy Principle: From 808s to therapy rooms to viral memes. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/

Comments ()