The Autistic Brain Isn't Broken—It's Tuned Differently

There's a way of experiencing the world that notices everything.

Every hum of a fluorescent light. Every flicker at the edge of vision. Every shift in someone's tone of voice. Every inconsistency in what they say versus what they do. Every pattern in the data. Every error in the logic. Everything.

For decades, this way of experiencing was called a disorder. A failure to filter. A deficit in social understanding. Something wrong that needed fixing.

The emerging science tells a different story. The autistic brain isn't broken—it's tuned differently. And that tuning, which creates real challenges in certain environments, also creates capacities that neurotypical processing lacks.

Understanding this requires understanding prediction. And understanding prediction reveals that autism isn't a deficit—it's an alternative architecture.

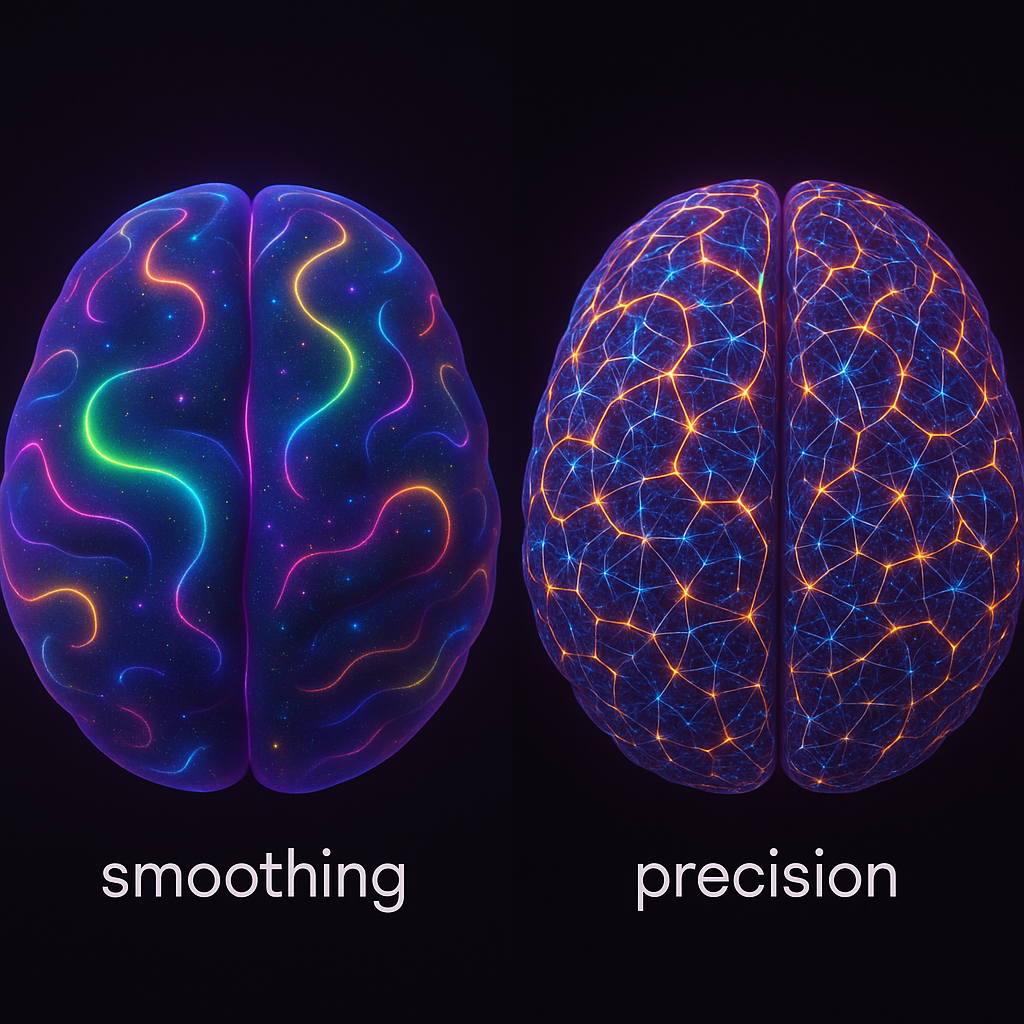

Precision and Smoothing

Remember: the brain is a prediction machine. It constantly generates expectations and compares them to incoming data. When predictions match, the world makes sense. When predictions fail, prediction error arises, demanding attention and update.

But prediction involves a choice: how much to trust the predictions versus how much to trust the data.

High precision means trusting the data heavily. Every signal gets taken seriously. Deviations from expectation register as significant and demand attention. Nothing gets smoothed over.

Low precision (or heavy smoothing) means trusting the predictions heavily. Small deviations get ignored. The system interpolates, filling gaps, maintaining stable expectations despite noisy input. The world looks more uniform than it actually is.

Most neurotypical processing leans toward smoothing. Social life works better when you're not tracking every micro-expression. Sensory processing is more efficient when you filter out irrelevant variation. Communication is easier when you assume shared context and don't flag every ambiguity.

Autistic processing often leans toward high precision. The signals don't get smoothed over. Every deviation from expectation registers. The world is experienced in higher resolution—not filtered into comfortable categories but encountered in its full, unsmoothed complexity.

What High Precision Feels Like

High precision is a gift and a burden.

The gift: you notice things others miss. The pattern in the data that everyone overlooked. The inconsistency in the argument that passed unquestioned. The subtle shift in someone's mood before they've said anything. The early warning signs of a system starting to fail.

The burden: you notice everything. The fluorescent buzz that everyone else has tuned out. The texture of fabric against skin. The too-loud ambient noise that makes concentration impossible. The cognitive dissonance when someone says "I'm fine" and their face says they're not.

High precision means less buffer between you and the raw world. What neurotypical processing smooths into a manageable stream arrives as an unfiltered flood. The prediction error budget fills fast.

This isn't hypersensitivity in the pathological sense—it's accurate sensitivity. The autistic person isn't imagining that the light is buzzing. The light is buzzing. Everyone else is just filtering it out.

Social Prediction Challenges

Social reality is especially challenging for high-precision systems.

Social interaction is ambiguous by design. Much of what's communicated is unstated. Tone, context, shared assumptions—all do heavy lifting. Neurotypical processing smooths over this ambiguity, filling in the gaps with learned heuristics, maintaining the illusion of clear communication.

High-precision processing doesn't smooth. It flags the ambiguity. It notices that the words don't quite match the tone. That the stated reason doesn't quite explain the behavior. That the social script has unstated exceptions that everyone else seems to know but nobody has explicitly mentioned.

This isn't lack of empathy. Many autistic people experience intense empathy—sometimes too intense, overwhelming empathy that floods them with others' emotions. It's not lack of theory of mind. It's that social reality is genuinely ambiguous, and high-precision processing doesn't paper over that ambiguity the way neurotypical processing does.

The "social deficit" is partly an artifact of measurement. When you test social understanding using tasks designed for neurotypical processing—tasks that reward smoothing, that punish precision—autistic people perform worse. But this says more about the test than about social understanding itself.

The Double Empathy Problem

For years, autism was framed as a failure to understand neurotypical minds.

But here's the flip: neurotypical people are equally bad at understanding autistic minds.

This is the "double empathy problem," identified by the autistic researcher Damian Milton. The difficulty isn't one-sided. It's a mutual failure to predict across different cognitive architectures.

Autistic people often understand each other just fine. Neurotypical people understand each other just fine. The challenge is at the interface—where two different prediction systems, tuned differently, try to coordinate and keep generating errors about each other.

This reframes everything. Autism isn't a social deficit within autistic people. It's a mismatch between cognitive architectures. The problem lives in the relationship, not in either party alone.

And this means the solution isn't just to train autistic people to mimic neurotypical processing. It's to build bridges—to help both sides predict each other better.

Environmental Fit

Autistic challenges are often environmental misfits.

A high-precision system in a low-precision environment is going to suffer. Offices with flickering lights, open floor plans with constant noise, meetings with unstated agendas, cultures that communicate indirectly—these are sensory and cognitive assaults on systems that don't smooth.

But a high-precision system in a matching environment thrives. Clear communication. Explicit expectations. Controlled sensory input. Logical structure. Consistency between what's said and what's meant.

The "deficit" is contextual. Put an autistic person in an environment designed for their architecture, and many of the supposed symptoms disappear. What looked like pathology was actually mismatch.

This is why autism presents so differently across individuals and across contexts. The underlying architecture may be similar, but the environments vary enormously. Some environments activate the challenges; others activate the gifts.

What High Precision Enables

High-precision processing has genuine advantages.

Pattern detection. When you're not smoothing over variation, you see patterns others miss. The anomaly in the dataset. The regularity hidden in the noise. The deep structure beneath the surface.

Quality assurance. When small deviations register, errors get caught. The typo. The inconsistency. The flaw that passed everyone else's inspection. High precision is natural quality control.

Logical consistency. When your predictions are tightly constrained by evidence, you're less susceptible to motivated reasoning. You notice when arguments don't hold. You flag the contradiction.

Systematizing. Many autistic people excel at building and maintaining complex systems—code, mathematics, collections, procedures. This makes sense: systematizing is precision-dependent. It requires tracking details that smoothing would obscure.

Deep focus. High precision can produce intense engagement with narrow domains. When the domain is well-matched, this focus enables extraordinary expertise. The "special interest" is precision applied productively.

These aren't consolation prizes. They're capabilities that neurotypical processing genuinely lacks. In complex, volatile, or high-stakes environments, high-precision sensing is essential.

Masking and Its Costs

Many autistic people learn to mask—to perform neurotypical behavior patterns that don't match their internal experience.

Masking is cognitively exhausting. It requires continuous monitoring of what's expected, continuous suppression of natural responses, continuous generation of performed responses. It's running a translation layer in real time, all the time.

The costs are severe. Chronic fatigue. Burnout. Loss of access to authentic preferences and responses. A sense of not knowing who you really are because who you've been performing isn't who you actually are.

Masking often develops in childhood as a survival strategy. The autistic child learns that authentic expression produces negative responses—confusion, rejection, punishment. They learn to hide. By adulthood, the mask can be so integrated that dropping it feels like losing identity.

But the mask is a prediction distortion. It teaches others to predict the mask, not the person. It creates relationships based on false models. When the mask eventually fails—as it tends to during burnout—the relationships that were built on it may fail too.

Unmasking and Authentic Coherence

Healing, for many autistic people, involves unmasking—rediscovering and expressing the authentic cognitive architecture that masking suppressed.

This isn't easy. The mask is often so thorough that the person doesn't know what's underneath. They've been performing so long that authentic preferences and responses are inaccessible. Unmasking requires excavation.

And it's risky. The world that required the mask still exists. Authentic expression may still produce negative responses from those who expect the performance.

But unmasking is also coherence restoration. When internal experience and external expression align, prediction errors between self-model and actual self decrease. The constant energy drain of translation ends. Authenticity feels like relief—like finally operating in native mode instead of constant translation.

From an active inference perspective, masking is maintaining a false generative model. You're generating outputs from a model that doesn't match your actual internal states. This is inherently unstable, metabolically expensive, and prone to collapse.

Authenticity is alignment between model and reality. It's easier. It's more sustainable. It costs less.

Neurodiversity as Cognitive Diversity

The broader point: cognitive diversity is real.

Autistic processing is one variant. ADHD is another. Other conditions represent other variations. Neurotypical processing is the most common—but "common" doesn't mean "correct" or "only valid."

Different cognitive architectures are suited to different environments and tasks. High-precision systems detect what smoothing systems miss. Novelty-seeking systems explore what stable systems ignore. Detail-focused systems catch what big-picture systems overlook.

A population with cognitive diversity has more collective capacity than a homogeneous population. Different nodes in the network contribute different functions. The system as a whole is more robust, more adaptive, more capable.

This isn't just tolerance. It's functional recognition. Neurodivergent contributions aren't charity cases—they're essential inputs that homogeneous systems can't provide.

Implications

If autism is alternative architecture rather than deficit, implications follow.

Accommodation isn't special treatment. It's removing environmental mismatches that disable a different architecture. Providing a quiet workspace isn't coddling—it's removing barriers.

Communication differences go both ways. Autistic people can learn to communicate with neurotypical people, and neurotypical people can learn to communicate with autistic people. The burden shouldn't fall entirely on one side.

Autistic perspectives have value. In fields requiring precision—science, technology, quality control, logical analysis—autistic contributions may be not just acceptable but essential.

Masking has costs. Expecting autistic people to perform neurotypicality indefinitely is expecting unsustainable self-injury.

The environment is part of the disability. Much of what disables autistic people is not their architecture but environments designed to exclude that architecture.

The autistic brain isn't broken. It's tuned to detect what others don't. In a world that's increasingly complex, increasingly volatile, increasingly dependent on catching errors early—that tuning may be exactly what's needed.

Explore the lattice →

M=T/C Theory Neurodiversity Science Active Inference Trauma & Attachment Computation & Physics Future Biology

Comments ()