The Neuroscientist Who Says You're Hallucinating Reality Right Now

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

Karl Friston doesn't look like a revolutionary.

The British neuroscientist, based at University College London, speaks in the measured tones of academic caution. His papers are dense with equations. His Wikipedia page reads like a CV from a particularly productive dream.

But the idea at the center of his work is radical enough to restructure everything we think we know about brains, minds, and what it means to be alive: You are not perceiving reality. You are generating it.

What you experience as the world—the colors, sounds, textures, objects, people—is not a direct readout of sensory data. It's a construction. A best guess. A controlled hallucination that your brain produces and your senses merely edit.

Friston didn't invent this idea. But he gave it mathematical form. And in doing so, he may have uncovered the operating principle that governs everything from bacterial navigation to human consciousness.

The Most Cited Neuroscientist Alive

By some measures, Karl Friston is the most influential neuroscientist in history. His statistical methods for analyzing brain imaging data—developed in the 1990s—are used in virtually every fMRI study. His software package, SPM, is the standard tool in the field.

But that's just the engineering. The theory is bigger.

Starting in the 2000s, Friston began developing a framework called the free energy principle—a mathematical account of how self-organizing systems maintain their existence. The claim is audacious: the same principle that explains how a bacterium navigates a chemical gradient explains how you decide what to have for breakfast.

The principle is simple to state, hard to fully grasp: any system that persists over time must minimize the difference between what it expects and what it encounters.

That's it. Minimize surprise. Stay aligned with your predictions. Or dissolve.

Prediction as Existence

Here's the core insight: living systems are prediction systems.

To remain organized—to continue existing as the particular pattern of matter that you are—you must occupy states that are consistent with your continued existence. You must stay within certain temperature ranges, maintain certain chemical balances, avoid certain physical configurations (like "digested by predator" or "spread across highway").

These are the states you expect to occupy. And you maintain them not by passively reacting to the world but by actively predicting it and shaping your behavior to fulfill those predictions.

Your body predicts that it will have sufficient blood glucose and acts to make that prediction true (by seeking food). Your brain predicts that the world will continue making sense and acts to maintain that prediction (by building coherent models and avoiding information that would shatter them).

Existence is self-fulfilling prophecy. You exist because you predict that you'll continue to exist—and then act to make that prediction true.

The Controlled Hallucination

So what is perception, in this framework?

It's not the passive reception of sensory information. It's the active construction of a model that generates sensory predictions, then updates that model based on prediction errors.

Friston calls this active inference. Others call it the predictive brain or predictive processing. The philosopher Andy Clark calls it the "prediction machine."

The upshot is strange and profound: what you experience as seeing the world is actually your brain's best guess about what's causing the patterns of light hitting your retina. What you experience as hearing is your brain's best guess about what's causing the patterns of pressure waves in your ear. All the way down.

You're not looking at reality. You're looking at a simulation of reality that your brain is running—a simulation that happens to be very, very good because it's constantly being corrected by sensory error signals.

This is why optical illusions work. They exploit the seams in your predictive model—places where the brain's assumptions about the world don't quite match the incoming data. The illusion reveals the construction. It shows you the hallucination.

But you're hallucinating all the time. The illusions just make it obvious.

Why This Matters

This isn't just philosophical wordplay. The predictive brain framework has concrete implications for understanding minds.

Attention becomes precision-weighting—the process of deciding which prediction errors to take seriously. You attend to what your brain decides is informative.

Learning becomes model-updating—the process of revising predictions to reduce future error. You learn when reality surprises you in ways that matter.

Action becomes prediction-fulfillment—the process of moving your body to make your predictions come true. You act not to respond to the world but to create the sensory states you expect.

Emotion becomes the felt sense of prediction error across the body. When predictions hold, you feel calm, coherent, at home in the world. When predictions fail, you feel anxious, confused, destabilized.

And psychopathology becomes prediction failure in specific domains. Depression may involve overly rigid models that can't update in response to positive information. Anxiety may involve models that over-predict threat. Psychosis may involve failures in distinguishing self-generated predictions from external reality.

The framework doesn't explain everything. But it provides a unified language for talking about phenomena that previously seemed unrelated.

The Markov Blanket

One of Friston's key concepts is the Markov blanket—the boundary between a system and its environment.

Every living thing has a Markov blanket. It's the statistical surface that separates inside from outside—the membrane through which the organism interacts with the world.

Your skin is part of your Markov blanket. So are your sensory surfaces—eyes, ears, touch receptors. These are the channels through which you receive information about the world. And your motor systems—muscles, vocal cords—are the channels through which you act on the world.

But the Markov blanket is not just physical. It's informational. It defines what you can know about the world (only through your senses) and what you can do to the world (only through your actions). Everything else—your internal states, your models, your predictions—lives behind the blanket, forever separated from direct access to reality.

This is why you hallucinate. You can never perceive reality directly. You can only infer it through the patterns that cross your Markov blanket.

Blankets All the Way Up

Here's where it scales.

Markov blankets don't just apply to individual organisms. They apply to any self-organizing system—any pattern that maintains itself against entropy.

A cell has a Markov blanket (its membrane). An organ has a Markov blanket (the boundaries that distinguish it from other organs). A person has a Markov blanket (the sensorimotor interface). A couple has a Markov blanket (the communication channels that constitute their relationship). An organization has a Markov blanket (its interfaces with customers, suppliers, regulators).

At each level, the same logic applies: the system must minimize prediction error across its blanket to maintain its organization. The system must predict its environment and act to fulfill those predictions. The system must exist by expecting to exist.

This gives Friston's framework extraordinary scope. It's not just a theory of brains. It's a theory of life—of what it means for any pattern to persist in a universe trending toward disorder.

The Critics

Not everyone is convinced.

Some philosophers argue that the free energy principle is too broad—that it's true of any self-organizing system by definition, and therefore explains nothing specific about minds or brains. It's a framework, not a theory. It tells you that systems minimize free energy, not how any particular system does it.

Some neuroscientists argue that the predictive processing story is too simple—that the brain does many things that don't fit neatly into prediction and error-correction. Creativity, play, exploration—how do these fit into a system optimized for minimizing surprise?

Friston has responses to these objections. On breadth: the framework's generality is a feature, not a bug. It provides a unified language that can then be instantiated in specific models for specific systems. On exploration: the system isn't just minimizing current surprise—it's also minimizing expected future surprise, which sometimes requires exploring, learning, and tolerating short-term uncertainty for long-term prediction accuracy.

The debates continue. But what's not debatable is that Friston's work has shifted the conversation. Even critics now frame their objections in the language he provided.

Hallucination as Home

If you're hallucinating reality, what does that mean for truth? For knowledge? For the feeling that you're in contact with a real world outside your head?

Friston's answer is deflationary. You're not cut off from reality—you're in constant contact with it, through the error signals that correct your predictions. Your hallucination is controlled precisely because it's constrained by reality. The simulation works because it's continuously updated by data.

But this changes the meaning of "knowing." You don't know the world by mirroring it. You know the world by modeling it—by building internal structures that can predict it well enough to navigate it. Truth becomes accuracy of prediction. Knowledge becomes coherence between model and reality.

And meaning? Meaning becomes the felt sense of that coherence holding. The experience of things making sense—of predictions aligning with outcomes, of the model fitting the world, of the hallucination matching the reality it represents.

Meaning is coherence under constraint. The constraint is the stream of prediction errors that reality sends your way. The coherence is your model's ability to accommodate those errors without breaking.

When coherence holds, you feel present, oriented, at home. When it breaks, you feel confused, dissociated, lost. The world doesn't change. Your predictions do.

The Quiet Revolution

Friston works in a small office in London, surrounded by equations and doctoral students. He's not on social media. He doesn't give TED talks. His papers require graduate-level mathematics to fully understand.

And yet his ideas are spreading—into philosophy of mind, into artificial intelligence, into clinical psychology, into our understanding of what life itself is.

If he's right, then every living thing is a prediction machine, generating its experience moment by moment, constantly hallucinating a world that it then uses action to make real.

You're not watching reality. You're dreaming it—and using your senses to keep the dream honest.

That's the revolution. It doesn't feel revolutionary because you've been doing it your whole life. The hallucination is seamless. The prediction is invisible.

Until, like now, someone points at it.

Explore the lattice →

M=T/C Theory Neurodiversity Science Active Inference Trauma & Attachment

Read next

Ten Testable Predictions from the Free Energy Principle

The Hydrogen Anchor Revisited: From Atoms to Coherence in One Geometric Principle

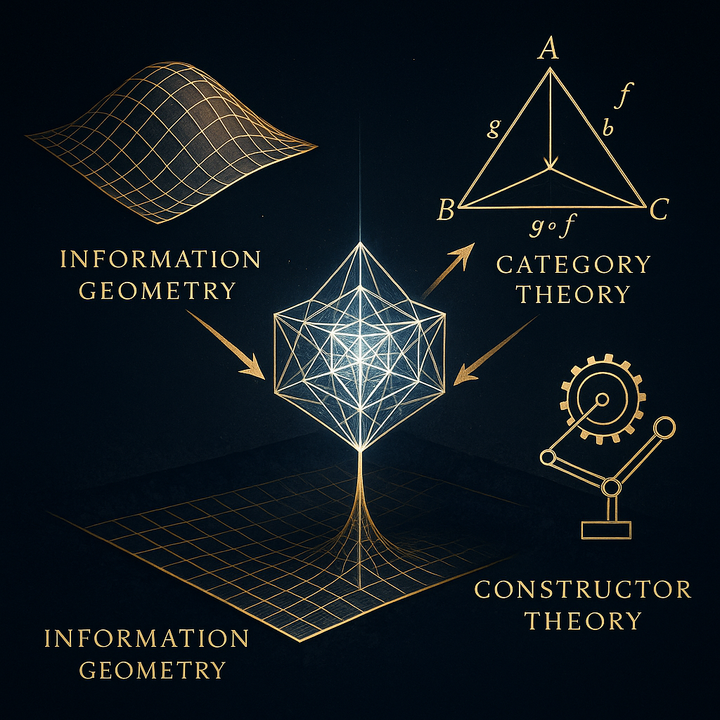

Why This Isn't Metaphor: The Mathematical Architecture Beneath Meaning

Comments ()