What Physics and Anxiety Have in Common: A New Theory of Mind

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

There's an equation that describes black holes, chemical reactions, and your panic attacks.

It sounds absurd. What could the mathematics of thermodynamics possibly have to do with the racing heart and spiraling thoughts of anxiety? What does entropy—the physicist's measure of disorder—have to do with whether you can get through a social gathering without falling apart?

More than you'd think.

The same principles that govern how energy dissipates in physical systems govern how information dissipates in cognitive systems. And the same drive that keeps matter organized against the universal tendency toward chaos keeps you organized against the pressures threatening to fragment your experience.

This is the deep insight behind the free energy principle: life and mind are not separate from physics. They're what physics looks like when matter gets organized enough to resist its own dissolution.

Energy Wants to Spread

Here's the second law of thermodynamics in plain English: energy spreads out.

A hot cup of coffee cools. A dropped egg splatters. A sandcastle erodes. In every case, organized energy becomes disorganized. Order decays into disorder. Gradients flatten.

This is entropy—the tendency of the universe toward equilibrium, toward the most probable distribution of matter and energy. The most probable state is almost always the most disordered state, because there are so many more ways to be disordered than ordered. There's one way to arrange a deck of cards in perfect sequence; there are billions of ways to arrange it randomly.

Left alone, physical systems drift toward disorder. This is the arrow of time. This is the universe's default mode.

And yet here you are—a fantastically organized system, maintaining your structure day after day, decade after decade. Your trillions of cells coordinate. Your organs function. Your thoughts cohere. You are deeply, improbably ordered.

How?

Swimming Against Entropy

Living systems are eddies in the entropic flow.

They're not exempt from the second law. They're exploiting it—using energy gradients to maintain their organization. A plant captures sunlight to build complex molecules. An animal eats other organisms to fuel its metabolism. Life feeds on order to resist disorder.

But it's not enough to simply consume energy. The system must use that energy strategically—to maintain the specific organization that keeps it alive. It must resist the particular ways it would dissolve if it didn't act.

This requires prediction.

To maintain yourself, you must anticipate what threatens you and act to prevent it. You must model the environment well enough to stay ahead of its challenges. You must predict the future to have a future.

This is where the free energy principle enters. Free energy, in this context, isn't the energy that's freely available. It's a measure of the mismatch between your internal model and sensory reality—a bound on the surprise you're experiencing.

High free energy means your predictions are badly wrong. Low free energy means your model fits the world. To minimize free energy is to minimize surprise—to maintain coherent predictions about a coherent world.

And to minimize surprise is to minimize entropy. A surprised organism is an organism whose internal states are becoming unpredictable, disordered, unconstrained. Surprise is disorder measured in information. It's entropy's cousin in the domain of the mind.

What Anxiety Actually Is

Now anxiety starts to make sense.

Anxiety is the felt experience of prediction failure. It's the signal that arises when your model of the world is generating errors faster than you can integrate them. When uncertainty spikes. When the future becomes opaque.

Think about what triggers anxiety: novel situations, ambiguous information, potential threats you can't assess, social contexts where you don't know the rules. These are all prediction failures. The anxious system is overwhelmed by surprise.

And the symptoms of anxiety are the organism's attempts to reduce surprise by any means necessary. Hypervigilance is an attempt to gather more information. Avoidance is an attempt to stay in predictable environments. Rumination is an attempt to model all possible outcomes. Control behaviors are attempts to constrain the environment so it matches predictions.

Anxiety isn't irrational. It's the rational response of a prediction system to excessive surprise—a system fighting to reduce free energy before it loses coherence entirely.

The problem is that the strategies often backfire. Hypervigilance gathers information but also raises the signal of threat. Avoidance reduces exposure but also prevents learning. Rumination models outcomes but keeps arousal elevated. Control works until it doesn't, at which point the system faces the accumulated surprise it tried to defer.

Anxiety is a prediction system in crisis mode, deploying every available strategy to minimize the mismatch between expectation and reality—often making the mismatch worse in the process.

The Geometry of Distress

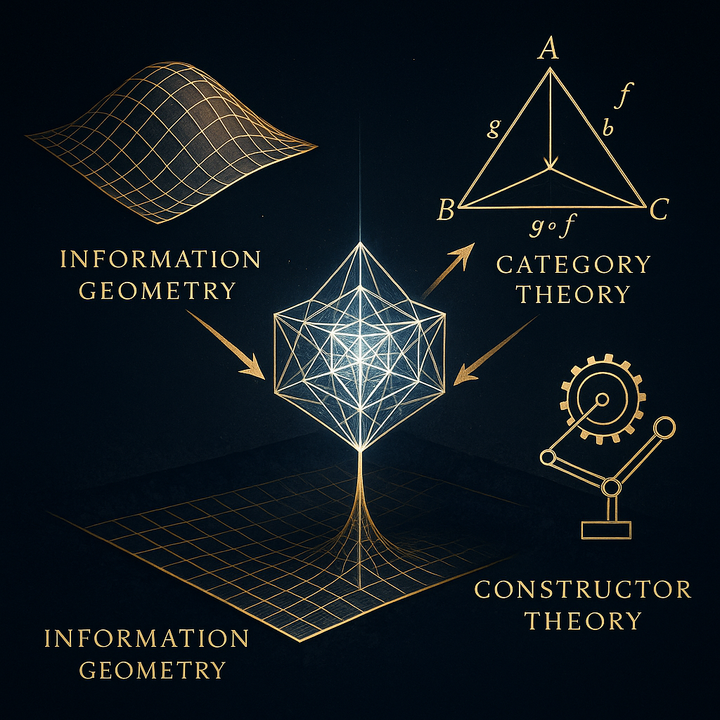

There's a way to visualize this.

Imagine your internal model as a surface—a landscape of predictions. Some regions of this landscape are smooth: predictions are accurate, errors are small, the system flows easily. Other regions are jagged: predictions fail, errors spike, navigation becomes difficult.

In mathematics, this smoothness or jaggedness is called curvature. A flat surface has low curvature—it doesn't bend sharply. A mountainous surface has high curvature—it's full of steep slopes and sudden transitions.

Anxiety is life on a high-curvature manifold.

Every small change in input produces a large change in output. Every minor uncertainty triggers major response. The system can't find stable ground because the ground keeps shifting beneath it. Walking through the landscape is metabolically expensive—you have to correct course constantly, never trusting the next step.

Trauma creates curvature spikes—regions of the manifold that deform so sharply that smooth navigation becomes impossible. The system can't cross these regions without destabilizing. So it routes around them, narrows its path, reduces the territory it's willing to traverse.

Depression is another curvature pathology—not spikes but collapse. The landscape flattens into shallow basins where movement is possible but pointless. Gradients are too subtle to generate motivation. The system is stable but stagnant, trapped in low-energy attractors it can't escape.

Coherence and Its Absence

What both anxiety and depression share is a breakdown in coherence—the capacity of the system to maintain integrated function across perturbation.

A coherent system is one where predictions align with reality across domains. Where body, emotion, thought, and behavior coordinate. Where the manifold is smooth enough for navigation and flexible enough for adaptation.

An incoherent system is one where predictions fail systematically. Where subsystems desynchronize. Where the manifold fragments into disconnected regions or collapses into rigid attractors.

Coherence isn't the absence of challenge. It's the capacity to meet challenge while maintaining organization. A coherent system can face uncertainty without dissolving. An incoherent system faces uncertainty and fragments.

This is why the same event can traumatize one person and leave another shaken but intact. Trauma isn't in the event—it's in the relationship between event and system. It's what happens when the surprise exceeds the system's capacity to integrate.

Coherence under constraint. That's what the physics describes. That's what the mathematics formalizes. That's what the lived experience of mental health—or its absence—reflects.

The Prediction-Error Budget

Every system has a prediction-error budget—a finite capacity for integrating surprise before coherence begins to degrade.

When prediction errors are small and occasional, the system handles them easily. You update your model. You learn. You adapt. No big deal.

When prediction errors are large or sustained, the budget gets strained. Each error consumes resources. The system starts prioritizing—focusing on the most threatening surprises, ignoring others, triaging its attention. You feel stressed, vigilant, increasingly narrowed.

When prediction errors exceed the budget entirely, the system fails to integrate them. The errors don't update the model—they overwhelm it. The model fragments or freezes. Experiences become unassimilated—stored as raw sensation rather than coherent memory. This is trauma.

Anxiety is life at the edge of the budget, constantly threatening to exceed it. The chronic sense that one more surprise will be too much. The system running at capacity with no reserves.

Depression is what happens after the budget was exceeded and the system shut down. The protective response of a system that learned its predictions are useless and its actions are futile. Why try to reduce surprise when trying has been punished?

Recovery is budget restoration. Building capacity. Expanding the prediction-error tolerance. Learning, slowly, that surprise can be survived—that the model can update, that coherence can return.

The Treatment Implications

If this framework is right, treatment for anxiety and depression isn't primarily about thoughts or behaviors—it's about prediction.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, from this view, works by updating predictions. You expose yourself to feared situations and discover they're less threatening than expected. Prediction error occurs, but this time it updates the model in a helpful direction. The manifold smooths.

Somatic therapies work by updating interoceptive predictions—the body's model of itself. Through breathwork, movement, or body awareness, you teach the body that it can tolerate arousal without catastrophe. The prediction that "elevated heart rate means danger" gradually revises.

Medication works by shifting the precision weighting—how heavily the system weighs different prediction errors. SSRIs may lower the precision of threat-related predictions, making them less attention-demanding, giving other signals room to be processed.

And relationship works by co-regulation—by borrowing someone else's coherence until your own can stabilize. A regulated nervous system in the room provides prediction signals your system can entrain to. The therapist's calm becomes a model your model can learn from.

All of these interventions reduce free energy. They bring the internal model into better alignment with reality. They smooth the curvature. They restore coherence.

Same Physics, Different Scale

Here's what's remarkable: the mathematics don't change as you move from thermodynamics to neuroscience to psychology.

The same principles that describe how a gas reaches equilibrium describe how a brain reaches coherence. The same equations that model chemical gradients model prediction error. The same drive that organizes dissipative structures in physics organizes minds in biology.

This isn't reduction—it's not claiming that psychology is "just physics." The substrates are different. The instantiations are different. A brain is vastly more complex than a gas cloud.

But the organizing principle is the same. Systems that persist must minimize surprise. They must predict their environments. They must maintain coherence under constraint. Whether they're made of molecules or neurons, the logic is identical.

This is why physics and anxiety connect. They're both descriptions of organization maintaining itself against entropy. They're both accounts of pattern resisting dissolution. They're both chapters in the same book about what it means for order to exist in a disordering universe.

You exist because your ancestors were thermodynamically clever. Your anxiety is the alarm that signals when that cleverness is being tested.

Comments ()