Angles: Measuring the Space Between Lines

An angle is not a shape. It's a measurement of rotation.

Forget two lines meeting at a point. That's how angles are drawn, not what they are. An angle measures how much you'd have to rotate one line to land on the other.

Here's the unlock: angles are about turning, not intersection. A 90-degree angle means "turn a quarter of the way around." A 180-degree angle means "turn until you're pointing backwards." The lines in the diagram are just showing you the before and after of the rotation.

Once you see angles as rotation, everything else follows — why there are 360 degrees in a circle, why perpendicular lines are special, why angles in a triangle sum to 180.

Why 360 Degrees?

Why not 100 degrees in a circle? Or 400? (France actually tried 400 during the Revolution.)

The answer is: 360 is arbitrary. There's nothing mathematically special about it. The Babylonians chose it about 4,000 years ago, probably because 360 divides evenly by 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 18, 20, 24, 30, 36, 40, 45, 60, 72, 90, 120, and 180.

That's absurdly divisible. It means common angles like quarter-turns (90°), third-turns (120°), and sixth-turns (60°) all come out as nice whole numbers.

Degrees are a convention, not a truth about angles. Radians — which we'll get to — are more mathematically natural.

The Unit Circle Definition

Here's the cleanest way to think about angles:

Stand at the center of a circle. Face some direction — call it 0°. Now rotate counterclockwise. How far you turn is the angle.

- Quarter turn: 90° — you're facing perpendicular to where you started

- Half turn: 180° — you're facing backwards

- Three-quarter turn: 270° — perpendicular the other way

- Full turn: 360° — you're back where you started

The angle measures the rotation from start to finish. The circle just makes it visible.

Acute, Right, Obtuse, Straight

Angles have names based on their size relative to key landmarks:

Acute (0° to 90°): Less than a quarter turn. Sharp.

Right (exactly 90°): A quarter turn. Perpendicular. The cornerstone of Euclidean geometry.

Obtuse (90° to 180°): More than a quarter turn but less than half. Blunt.

Straight (exactly 180°): A half turn. The lines form a single straight line.

Reflex (180° to 360°): More than half a turn. Going the long way around.

Right angles are special because they represent perpendicularity — two directions that are as different as possible. This is why right angles get their own symbol: that little square in the corner.

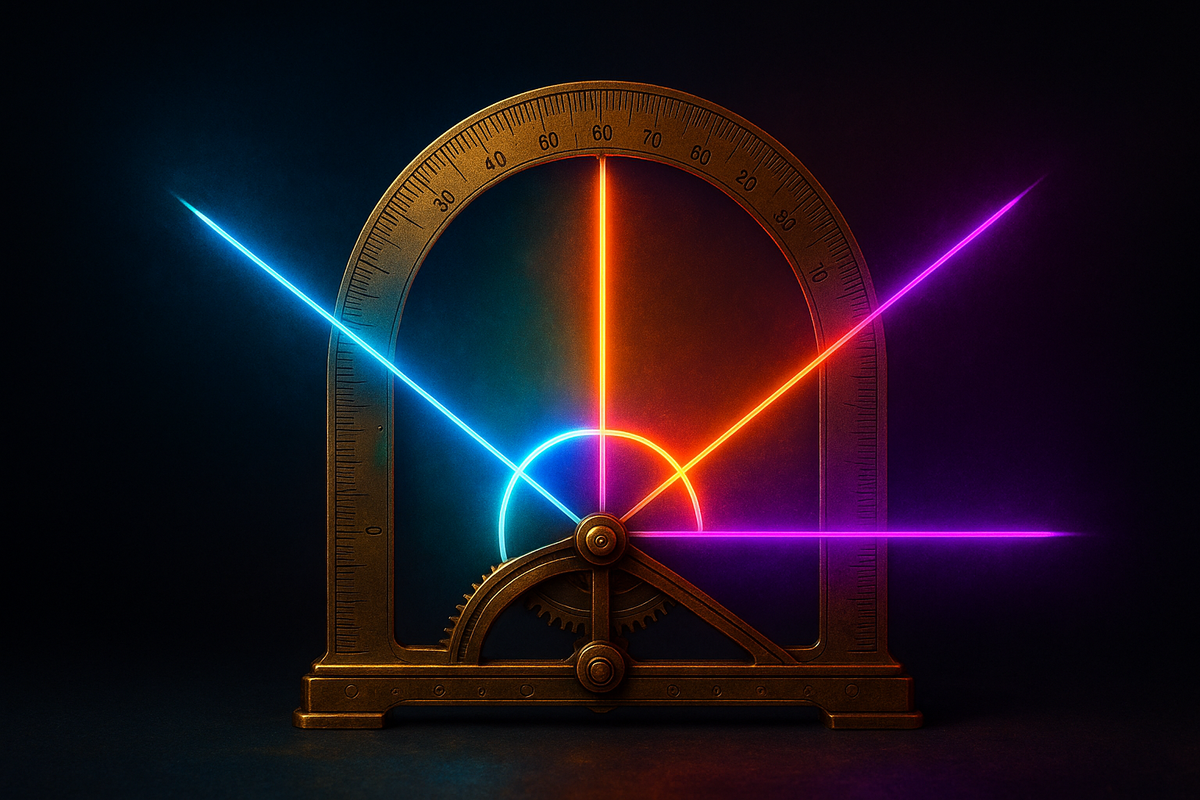

Measuring Angles

You don't need a protractor to understand angles. The protractor just reads off the rotation for you.

But there are two ways to measure the "same" angle between two lines — the angle and its supplement. If two lines cross, they form four angles, and adjacent angles always sum to 180°.

When someone says "the angle between these lines is 30°," they usually mean the smaller one. The other angle would be 150°.

Complementary and Supplementary

Two important relationships:

Complementary angles sum to 90°. If one angle is 30°, its complement is 60°. Together they make a right angle.

Supplementary angles sum to 180°. If one angle is 30°, its supplement is 150°. Together they make a straight line.

These relationships matter because they let you find unknown angles. If you know two angles are supplementary and one is 110°, the other must be 70°.

Angles When Lines Cross

When two lines cross, they form four angles. These angles have special relationships:

Vertical angles are opposite each other. They're always equal. If the intersection creates a 40° angle, the angle directly across is also 40°.

Linear pairs are adjacent angles. They're always supplementary (sum to 180°). If one angle is 40°, its neighbor is 140°.

So a single intersection of two lines creates just two distinct angle measures — each appearing twice, adding up to 360°.

Angles with Parallel Lines

When a line crosses two parallel lines (a transversal), it creates eight angles — but only two distinct measures.

Corresponding angles are equal. Same position at each intersection.

Alternate interior angles are equal. Opposite sides of the transversal, between the parallel lines.

Co-interior angles (same-side interior) are supplementary. Same side of the transversal, between the parallel lines.

These relationships are how you prove lines are parallel, or find unknown angles when parallelism is given. They're consequences of what "parallel" means.

The Triangle Sum

Here's why angles in a triangle sum to 180°:

Draw a triangle. Extend one side into a line. Draw another line through that vertex, parallel to the opposite side.

Now count angles. The angle of the triangle plus two angles along the parallel line. But those two angles equal the other two triangle angles (alternate interior angles with parallel lines).

The three triangle angles, rearranged, form a straight line. 180°.

This isn't a coincidence. It's a consequence of the parallel postulate — Euclid's fifth axiom. In geometries where the parallel postulate fails, triangles don't sum to 180°.

Radians: The Natural Measure

Degrees are convenient but arbitrary. Radians are intrinsic.

One radian is the angle where the arc length equals the radius. Wrap the radius around the circumference — that's one radian.

Since a circle's circumference is 2πr, there are 2π radians in a full circle. So:

- Full turn: 2π radians ≈ 6.28 radians

- Half turn: π radians ≈ 3.14 radians

- Quarter turn: π/2 radians ≈ 1.57 radians

Why are radians "natural"? Because they make calculus work cleanly. The derivative of sin(x) equals cos(x) — but only if x is in radians. In degrees, you'd need ugly conversion factors.

Radians connect angle measure to arc length directly, without arbitrary constants.

Angles in Three Dimensions

In 2D, an angle is formed by two rays from a common point.

In 3D, you also get solid angles — formed by a cone of directions from a point. Measured in steradians. A full sphere is 4π steradians.

But even in 3D, regular angles still matter. The angle between two vectors. The angle a line makes with a plane. Dihedral angles where two planes meet.

The concept is the same: how much rotation to get from one direction to another.

Why Angles Matter

Angles are how geometry measures relationship between directions.

Parallel means the angle is 0°. Perpendicular means 90°. The angle between two paths tells you how similar or different those directions are.

In physics, the angle at which light hits a surface determines how it reflects. The angle of a ramp determines how hard it is to push something up. The angle of attack on a wing determines whether you fly or stall.

Angles are everywhere because direction is everywhere, and angle is the measure of how directions relate.

The Core Insight

An angle is rotation made measurable.

Not two lines meeting — that's just how we draw it. An angle is "how much turn from here to there."

Everything else — the relationships when lines cross, the theorems about parallel lines, the sum in triangles — follows from this basic idea. Angles measure rotation. Rotations compose. The math works out.

When you see an angle, don't see a shape. See a turn.

Part 3 of the Geometry series.

Previous: Points Lines and Planes: The Building Blocks of Space Next: Triangles: The Simplest Polygon and the Strongest Shape

Comments ()