Anxious-Avoidant Relationships: The Push-Pull Dynamic Explained

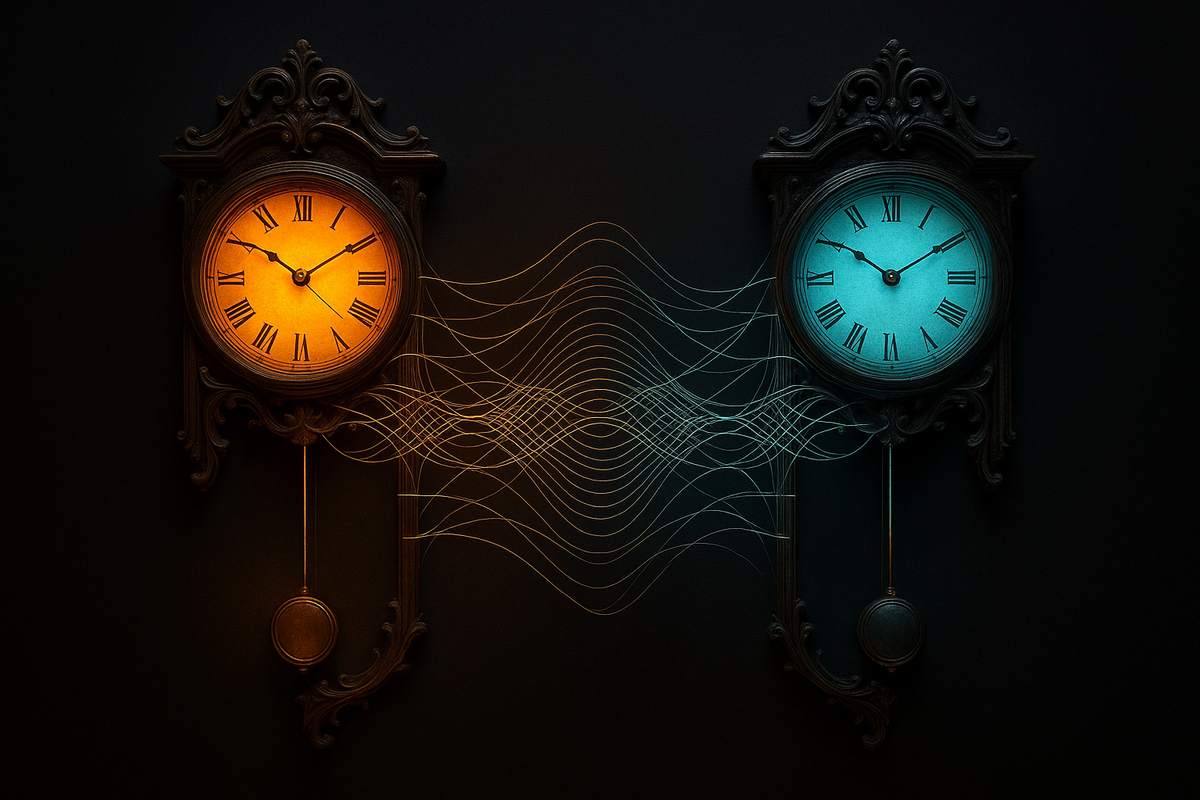

In 1665, Christiaan Huygens observed something strange about two pendulum clocks mounted on the same wall. Left alone, they eventually synchronized—their pendulums swinging in perfect antiphase, one reaching left as the other reached right. The wall transmitted vibrations between them. The clocks entrained.

Now imagine two clocks trying to synchronize, but one is running twice as fast as the other. One accelerates when it detects proximity. The other slows down or stops entirely. They're both trying to regulate—to find a stable rhythm—but their operating systems are fundamentally incompatible. The faster clock speeds up in response to connection. The slower clock shuts down in response to the same stimulus.

This is the anxious-avoidant relationship.

Not a personality clash. Not a communication failure. Not even, primarily, a psychological issue. It's two nervous systems trying to co-regulate while running on incompatible threat-detection algorithms. One system interprets distance as danger and accelerates toward contact. The other interprets proximity as danger and retreats into self-protection. They're both trying to achieve safety, but the actions that restore equilibrium for one destabilize the other.

This is the most common, most painful, and most misunderstood relationship pattern in attachment research. It's not dysfunctional because people are broken. It's dysfunctional because the coupled system cannot reach a stable equilibrium. The mathematics don't work.

Why This Pairing Is So Common: The Trap of Complementary Dysfunction

Here's the paradox: anxious-avoidant pairings are over-represented in relationship research. If attachment styles were randomly distributed, you'd expect anxious and avoidant individuals to avoid each other—they're clearly incompatible. But they don't. They find each other with eerie reliability.

Why?

Because in the early stages of a relationship, the patterns look like they fit.

An anxious person is drawn to an avoidant partner's initial calm, self-sufficiency, and emotional stability. After a lifetime of feeling too much, too intensely, they meet someone who appears grounded, unbothered by relational turbulence, immune to the anxiety that wracks them. The avoidant partner reads as secure. They're not anxiously texting, not demanding reassurance, not spiraling. They seem like the stable attachment figure the anxious person has been searching for.

The avoidant person is drawn to an anxious partner's enthusiasm, emotional expressiveness, and desire for connection. After a lifetime of keeping people at arm's length, they meet someone who actually wants them—who pursues, who initiates, who isn't scared off by distance. The anxious partner does the relational labor the avoidant person has always avoided. They text first. They plan dates. They tolerate ambiguity and keep showing up. The anxious partner seems like they'll never leave, which makes it safe for the avoidant to let them in—just a little.

Early dating rewards this dynamic. The anxious person gets attention. The avoidant person gets pursued without having to be vulnerable. Both feel like they've found someone different from past partners.

The problem emerges when the relationship deepens and the attachment system fully activates.

The Activation Cascade: When Nervous Systems Go Out of Phase

Attachment isn't about casual dating. It's about bonding—the biological process by which one person's nervous system begins to rely on another person's presence for regulation. This happens slowly, then all at once. Usually around 6-12 months into a relationship, sometimes sooner if there's early sexual bonding or cohabitation.

Once the attachment system activates, the dynamic flips.

For the anxious partner, the initial pursuit phase ends. Now they need reassurance—frequent contact, emotional availability, validation that the bond is secure. Their nervous system is running in sympathetic overdrive, scanning constantly for signs of disconnection. Every delayed text, every pulled-back expression, every "I need space" triggers a threat response. The system ramps up: text more, seek more contact, demand more reassurance.

For the avoidant partner, the deepening bond triggers a different alarm: engulfment. Their nervous system is wired to interpret intimacy as a loss of autonomy, a threat to self-integrity. As the anxious partner accelerates toward them, the avoidant partner's defenses activate. They withdraw—physically, emotionally, communicatively. They need space, time alone, emotional distance to feel regulated again.

Here's where the coupled system destabilizes:

Anxious nervous system detects distance → interprets as abandonment → activates protest behavior (pursue, demand, escalate) → avoidant nervous system detects pursuit → interprets as intrusion → activates deactivation (withdraw, shut down, create distance) → anxious nervous system detects increased distance → interprets as confirmation of abandonment → escalates further.

This is a positive feedback loop—each person's regulatory attempt amplifies the other's dysregulation. The system doesn't converge. It oscillates with increasing amplitude until something breaks.

Attachment researchers call this the anxious-avoidant trap or the pursuer-distancer dynamic. Engineers would recognize it as a control system with opposing feedback gains that prevent stable oscillation. Two coupled oscillators that cannot entrain.

What It Looks Like: The Protest-Withdrawal Cycle

The pattern shows up in predictable behavioral sequences.

Phase 1: The Trigger

Something activates the anxious partner's attachment system. Often it's subtle—a partner seeming distracted, a canceled plan, a day without much communication. For a secure person, these are normal fluctuations. For an anxious nervous system, they're threat signals.

The anxious partner reaches out: "Are you okay?" "Are we okay?" "I feel like you're pulling away."

Phase 2: The Pursuit

The avoidant partner, now feeling pressured, responds with some combination of: - Reassurance that feels hollow or irritated ("I'm fine, you're overthinking") - Minimization ("You're being too sensitive") - Deflection ("I just need some space") - Withdrawal (slower responses, physical distance, emotional shutdown)

This doesn't calm the anxious partner. It confirms the threat. The anxious partner escalates: - More frequent contact attempts - Emotional intensity increases - Accusations of not caring - Demands for reassurance or proof of love - Sometimes anger, sometimes desperate pleading

Phase 3: The Withdrawal

The avoidant partner, now overwhelmed, fully deactivates: - Goes silent - Becomes cold, detached, or critical - Physically leaves (walks out, stays away) - Invokes the need for "space" or "time to think" - May threaten the relationship ("Maybe this isn't working")

The anxious partner, now in full panic, either: - Continues pursuing (calling, showing up, demanding contact) - Collapses into despair (stops reaching out, waits in agony) - Experiences acute psychological distress (panic attacks, suicidal ideation, physical symptoms)

Phase 4: The Reunion

Eventually, one of two things happens:

Path A: The avoidant partner, having gained enough distance to feel regulated, re-engages. They reach out. They apologize or act like nothing happened. The anxious partner, desperate for reconnection, accepts immediately. Relief floods both nervous systems. The anxious partner feels chosen again. The avoidant partner feels safe again because the pressure is off.

Path B: The anxious partner, exhausted, gives up. They pull back. The avoidant partner, no longer feeling pursued, suddenly feels safe enough to approach. They miss the connection. They reach out. The cycle reverses briefly—now the avoidant is pursuing and the anxious is withdrawing—until the anxious partner's nervous system resets, they re-engage, and the original dynamic resumes.

Either way, the reunion brings temporary relief. Both partners feel like "things are good again." But the underlying nervous system patterns haven't changed. The next trigger will restart the cycle.

The Frequency Mismatch: Why Talking Doesn't Fix It

Couples in this dynamic talk. Constantly. They process, they negotiate, they promise to do better. The anxious partner tries to explain their needs. The avoidant partner tries to explain their boundaries. Both feel unheard.

Here's why: the conflict isn't cognitive. It's autonomic.

When an anxious nervous system is in sympathetic activation—heart rate elevated, cortisol spiking, amygdala firing—it's not interpreting the partner's words through a rational lens. It's scanning for threat. Every "I need space" reads as "I don't want you." Every "You're overthinking" reads as "You don't matter." The ventral vagal system—the part that enables calm social engagement—is offline. The person is in fight-or-flight, and fight-or-flight doesn't do nuance.

When an avoidant nervous system is in dorsal vagal shutdown—collapsed, numb, defended—it's not emotionally available. The person might be talking, might even be saying the "right" things, but there's no relational energy behind it. They're in protective immobilization. The anxious partner can feel this—they're detecting the absence of ventral vagal engagement, the lack of warmth, the emotional vacancy—and it activates their system further.

So the anxious partner is speaking from sympathetic overdrive, and the avoidant partner is speaking from dorsal shutdown, and neither is actually in a state where connection is neurologically possible.

This is why conversations that should resolve conflict often make things worse. The anxious partner hears withdrawal as rejection. The avoidant partner hears pursuit as attack. Both are correct—they're reading the other nervous system accurately. But they're each responding in ways that escalate the threat for the other.

The system is coherent at the level of each individual nervous system. It's incoherent at the level of the coupled dyad.

Entrainment Theory: What Would Stable Coupling Look Like?

In physics, coupled oscillators entrain when they have compatible natural frequencies and sufficient coupling strength. Two pendulums with similar swing rates can find a shared rhythm. Two drastically different frequencies cannot—they'll oscillate chaotically or one will dominate the other.

In attachment terms, secure partners entrain. Their nervous systems co-regulate. One partner's calm helps down-regulate the other's stress. Ruptures happen—conflict, misunderstanding, disconnection—but repair is possible because both nervous systems can return to ventral vagal engagement. The system has negative feedback: stress activates, connection soothes, baseline is restored.

Anxious-avoidant couples cannot entrain because their systems have opposing regulation strategies:

- Anxious system regulates through proximity. Threat is resolved by moving closer, seeking reassurance, increasing contact. Safety = connection.

- Avoidant system regulates through distance. Threat is resolved by moving away, reducing demand, creating space. Safety = autonomy.

These aren't compatible. They're antithetical. One partner's safety behavior is the other partner's threat stimulus.

The relationship oscillates but never stabilizes. Instead of entrainment, you get phase-locking in conflict—a stable pattern of instability, where the predictable cycle itself becomes the organizing structure.

Researchers studying dynamical systems call this an unstable equilibrium: the system has a pattern, but the pattern itself is destabilizing. The couple knows how the fight goes. They can predict the sequence. But prediction doesn't stop the cycle. It just makes it more entrenched.

Why This Hurts More Than Other Relationship Problems

Anxious-avoidant dynamics are uniquely painful because both partners are experiencing chronic nervous system dysregulation.

For the anxious partner: - Constant hypervigilance and threat detection - Repeated activation of the panic/abandonment response - Inability to down-regulate or find lasting reassurance - Shame about being "needy" or "too much" - Intermittent reinforcement (the partner returns sometimes, which makes the pursuing behavior impossible to extinguish)

For the avoidant partner: - Constant sense of intrusion and boundary violation - Repeated need to shut down and defend - Guilt about withdrawing but inability to stay engaged - Feeling blamed for the partner's distress - Resentment at being cast as the "bad guy" when they're also just trying to survive

Both are suffering. Both are doing the best they can with the nervous systems they have. And both are trapped in a relational structure that makes change nearly impossible from within the dynamic.

The relationship itself becomes a source of trauma—new attachment injuries layered on top of the old ones. Each cycle deepens the pattern. The anxious partner becomes more desperate. The avoidant partner becomes more defended. The space where secure attachment could develop shrinks.

Can Anxious-Avoidant Couples Make It Work?

Short answer: rarely, and only with significant individual work outside the relationship.

Here's why it's so hard:

The dynamic itself prevents the conditions necessary for change. To shift from anxious to secure, a person needs repeated experiences of seeking connection and being met with reliable, attuned responsiveness. To shift from avoidant to secure, a person needs repeated experiences of being close without being engulfed, and expressing needs without being rejected.

An anxious-avoidant couple cannot provide these experiences for each other. The avoidant partner can't offer consistent attunement—they're too defended. The anxious partner can't offer closeness without pressure—they're too dysregulated.

Change requires:

1. Individual nervous system regulation work. Both partners need to develop the capacity to self-regulate—to bring their own nervous systems back to baseline without relying on the other person. For the anxious partner, this means learning to down-regulate sympathetic activation (somatic therapy, breathwork, grounding techniques). For the avoidant partner, this means learning to stay present and engaged instead of shutting down (learning to tolerate discomfort, reconnect with emotion).

2. Rupture and repair practice with a secure third party. Both partners need to experience what healthy co-regulation feels like—usually through therapy, secure friendships, or other relationships where they can learn new patterns. You can't learn secure attachment from an insecure partner. You need corrective relational experiences with people who are already securely attached.

3. Temporary distance to break the cycle. Sometimes the only way to stop the feedback loop is to reduce coupling strength—spend less time together, take breaks, create space for both nervous systems to return to baseline. This is counterintuitive and often intolerable for the anxious partner, but it's sometimes necessary to prevent the dynamic from calcifying further.

4. Both partners actively choosing to change. This is the rarest ingredient. Change is hard. It requires confronting deeply defended patterns, doing uncomfortable nervous system work, and tolerating the vulnerability of trying new behaviors. Most often, one partner is willing and the other isn't. Or both are willing in theory but not in practice.

The research is not encouraging. Long-term studies of anxious-avoidant couples show high rates of dissolution. The relationships that survive tend to settle into chronic low-grade misery—both partners resigned to the pattern, no longer expecting it to change. Some couples report this as "realistic" or "mature." Attachment researchers would call it stabilized dysfunction.

The relationships that transform successfully usually involve at least one partner doing years of therapy, developing secure attachments elsewhere (with friends, therapists, or in a subsequent relationship), and then either returning to the relationship with new capacities or leaving and applying what they've learned with a more compatible partner.

The Coherence Lens: What's Actually Happening

From a coherence perspective, the anxious-avoidant dynamic is a coupled system with incompatible coherence-maintenance strategies.

Coherence, in the AToM framework (M = C/T), is the property of a system that allows it to maintain integrated function over time under constraint. A coherent nervous system can flexibly shift between states, integrate information, and return to baseline. High coherence = stable, adaptive function. Low coherence = fragmented, rigid, or chaotic function.

Each attachment style represents a coherence strategy:

- Secure attachment = high coherence. The nervous system can flexibly regulate, integrate relational data, tolerate rupture and repair. Meaning is maintained across relational variability.

- Anxious attachment = coherence maintained through hypervigilance. The system stays organized by constant monitoring and connection-seeking. High tension, moderate coherence (the system is organized, but fragile).

- Avoidant attachment = coherence maintained through disconnection. The system stays organized by minimizing relational input and self-reliance. Moderate tension, moderate coherence (the system is stable but rigid).

When an anxious and avoidant person couple, their individual coherence strategies conflict at the dyadic level. The anxious partner's strategy (maintain coherence through connection) destabilizes the avoidant partner's strategy (maintain coherence through autonomy). The avoidant partner's strategy destabilizes the anxious partner's strategy.

The result is a dyadic system with low relational coherence. Both individuals might maintain some internal coherence through their respective strategies, but the relationship itself cannot cohere. It oscillates, fragments, or collapses under relational stress.

Meaning, in this context, is the experience of "this relationship makes sense" or "we can navigate this together." That meaning erodes with each cycle. The relationship becomes progressively less meaningful—not because the individuals don't care, but because the structure cannot maintain integration over time.

From the outside, therapists and friends see it clearly: this relationship is incoherent, it's harming both people, it needs to end. From the inside, both partners are clinging to the relationship as a source of meaning, precisely because their attachment systems are activated. The bond itself—even a painful one—feels like coherence, because the alternative (separation) feels like system collapse.

This is the cruelest feature of anxious-avoidant dynamics: the relationship that is destroying coherence is also the thing both nervous systems are trying to use to maintain it.

What to Do If You're in This Dynamic

If you recognize yourself in this description—either as the anxious partner or the avoidant one—here's what the research and clinical practice suggest:

1. Name the pattern. Understanding that this is a nervous system dynamic, not a character flaw, can reduce shame and blame. You're not "crazy" or "emotionally unavailable." You're running an attachment strategy that was adaptive once but is now creating relational instability.

2. Stop trying to fix it through the relationship. Anxious partners: more communication will not make the avoidant partner more available. Avoidant partners: more space will not make the anxious partner less anxious. The problem is not insufficient communication or boundaries. It's incompatible nervous system states. Talking is not the intervention.

3. Get individual support. Therapy, somatic work, secure friendships. Both partners need to experience co-regulation with someone who is not triggering their system. You cannot learn secure attachment from an insecure partner.

4. Learn nervous system regulation. Anxious partners: learn to self-soothe, down-regulate, tolerate discomfort without seeking reassurance. Avoidant partners: learn to stay present, tolerate emotion, and communicate needs without shutting down. These are body-based skills, not cognitive ones.

5. Be realistic about whether this relationship can change. If both partners are actively doing the work, change is possible but slow—think years, not months. If one or both partners are not willing or able to do deep nervous system work, the dynamic will persist. Sometimes the most coherent choice is to leave.

6. If you leave, do the work before the next relationship. Anxious and avoidant individuals tend to recreate the same dynamics with new partners. The pattern will follow you until the underlying nervous system strategy changes. Leaving a bad relationship is necessary but not sufficient for building secure attachment.

The Bigger Question: Why Do We Keep Running This Program?

Attachment theory tells us that anxious and avoidant strategies are learned in childhood—adaptations to specific caregiving environments. The anxious pattern emerges with inconsistent caregivers: sometimes attuned, sometimes absent, teaching the infant that connection is possible but unreliable. The avoidant pattern emerges with rejecting or intrusive caregivers: teaching the infant that expressing need makes things worse.

Both strategies worked, once. They were coherence-maintenance solutions under constraint. The problem is that they continue running in adulthood, even when the original constraints no longer apply.

The question isn't "Why can't I just be secure?" The question is: What conditions would allow my nervous system to update its model?

For the anxious partner: repeated experiences of seeking connection and being met with attuned, reliable, non-abandoning responsiveness. For the avoidant partner: repeated experiences of expressing needs and being met with respect, not intrusion or rejection.

These are not experiences an anxious-avoidant couple can provide for each other. But they are experiences that can be found elsewhere—in therapy, in secure friendships, in new relationships, in reparative family dynamics.

The nervous system is plastic. The internal working model can be rewritten. But it requires new data, over time, in a relational environment that doesn't reactivate the old defenses.

Anxious-avoidant relationships are painful because they provide the opposite: continuous reinforcement of the very patterns both people are trying to escape. The anxious partner's worst fear (abandonment) is repeatedly confirmed. The avoidant partner's worst fear (engulfment) is repeatedly confirmed.

No amount of love, commitment, or effort can overcome that structural problem. The only solution is to change the structure—which means changing the nervous systems involved.

Further Reading

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books. - Levine, A., & Heller, R. (2010). Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find—and Keep—Love. TarcherPerigee. - Johnson, S. M. (2008). Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love. Little, Brown Spark. - Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. W. W. Norton. - Gottman, J. M., & Silver, N. (1999). The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. Crown. - Tatkin, S. (2012). Wired for Love: How Understanding Your Partner's Brain and Attachment Style Can Help You Defuse Conflict and Build a Secure Relationship. New Harbinger.

This is Part 7 of the Polyvagal Attachment series, exploring how attachment patterns are encoded in the autonomic nervous system. Next: "Relationship Anxiety: When Your Nervous System Can't Trust Connection."

Comments ()