ATP: The Energy Currency of Life

Right now, as you read this sentence, your body is producing about 40 kilograms of ATP.

Not over your lifetime. Not per year. Per day. Every single day, you synthesize roughly your body weight in adenosine triphosphate—the molecule that powers nearly every energy-requiring process in your cells.

You don't stockpile it. You can't. At any given moment, your body contains only about 250 grams of ATP. It's being made and consumed so fast that the entire pool turns over hundreds of times daily. The molecule that fuels your thoughts, your heartbeat, your every movement is being manufactured continuously, in every cell, by the trillions of mitochondria you inherited from an ancient bacterial ancestor.

This is the engine of life. And it's astonishingly efficient.

ATP is the universal energy currency. Everything your body does—every thought, every muscle fiber twitch, every protein folded—pays for it in ATP.

The Molecule

ATP stands for adenosine triphosphate. Let's break it down.

Adenosine is a nucleoside—adenine (one of the bases in DNA and RNA) attached to a ribose sugar. So far, nothing special.

The magic is in the triphosphate: three phosphate groups chained together, attached to the ribose. Phosphate groups are negatively charged. They repel each other. Forcing three of them together is like compressing a spring—the molecule stores potential energy in those bonds.

When ATP is hydrolyzed—when one phosphate group is cleaved off, producing ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and inorganic phosphate—energy is released. About 7.3 kilocalories per mole under standard conditions, more under cellular conditions.

That energy drives everything. Muscle contraction couples to ATP hydrolysis. Ion pumps across membranes couple to ATP hydrolysis. DNA replication, protein synthesis, cell division—ATP hydrolysis. The cell treats ATP as cash, spending it everywhere.

ATP isn't the only energy carrier, but it's the dominant one. The others are mostly there to recharge it.

Making ATP: The Overview

Cells have several ways to make ATP, but the big one—the one that produces the majority of ATP in most cells—is oxidative phosphorylation. This happens in mitochondria.

The overall process has two main phases:

Phase 1: Generate electron carriers. When you metabolize food (glucose, fatty acids, amino acids), you don't immediately produce ATP. You produce NADH and FADH₂—molecules that carry high-energy electrons. These electrons are captured during glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and beta-oxidation of fats.

Phase 2: Use electrons to power ATP synthesis. The electron carriers feed their electrons into the electron transport chain on the inner mitochondrial membrane. The electrons cascade through a series of protein complexes, releasing energy. That energy pumps protons across the membrane, creating a gradient. The gradient drives ATP synthase, which manufactures ATP.

This two-step process—extract electrons from food, then use electrons to power ATP production—is how mitochondria turn your lunch into your afternoon.

The Electron Transport Chain

The inner mitochondrial membrane is where the action happens. Embedded in it are four protein complexes (I, II, III, IV) plus two mobile electron carriers (ubiquinone and cytochrome c).

Here's the flow:

Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) accepts electrons from NADH. As electrons pass through, energy is released and used to pump protons from the matrix (inside) to the intermembrane space (outside).

Complex II (succinate dehydrogenase) accepts electrons from FADH₂ via succinate. It doesn't pump protons, so it contributes less to the gradient.

Ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) is a small, lipid-soluble molecule that ferries electrons from Complex I and II to Complex III.

Complex III (cytochrome bc1) accepts electrons from ubiquinone, pumps more protons, and passes electrons to cytochrome c.

Cytochrome c is a small protein on the outer surface of the inner membrane. It carries electrons from Complex III to Complex IV.

Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) accepts electrons from cytochrome c and pumps more protons. At the end of the chain, the electrons finally combine with oxygen and protons to form water. This is why you breathe: to supply oxygen as the final electron acceptor.

Oxygen is the drain at the end of the electron cascade. Without it, the whole system backs up.

The Proton Gradient

As electrons flow through Complexes I, III, and IV, protons get pumped across the inner mitochondrial membrane. The matrix becomes relatively negative; the intermembrane space becomes relatively positive.

This creates a proton-motive force—a combination of electrical potential (voltage difference) and chemical potential (concentration difference). Protons "want" to flow back into the matrix. They can't cross the membrane directly—it's impermeable to ions. They need a channel.

Enter ATP synthase.

ATP Synthase: The Molecular Turbine

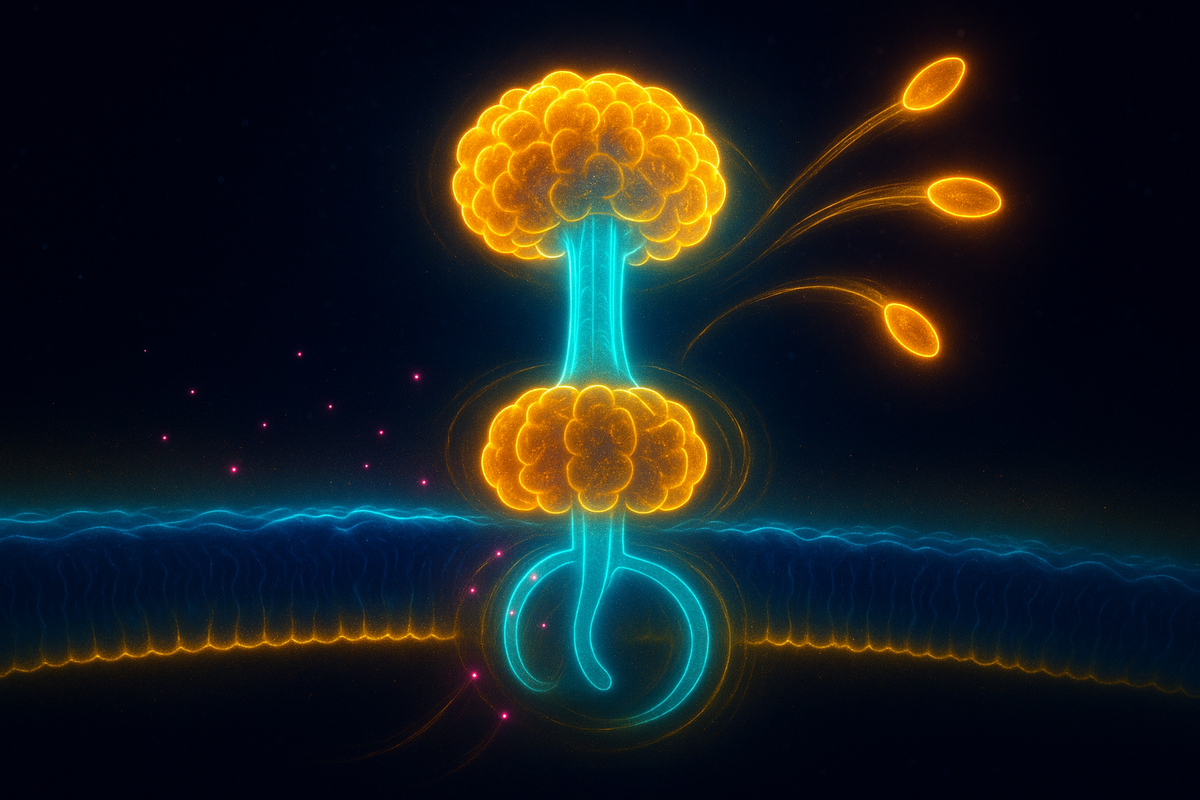

ATP synthase is one of the most remarkable molecular machines ever discovered.

It's a rotary motor. Literally. Protons flow through it, and their passage causes a rotor to spin. The spinning rotor drives conformational changes in the enzyme that catalyze ATP synthesis.

The structure has two main parts:

F₀ is embedded in the membrane. It contains the proton channel. As protons flow through, they push against a ring of subunits, causing it to rotate—like water turning a waterwheel.

F₁ is the catalytic head, protruding into the matrix. It's held stationary while the rotor inside it spins. The rotation drives a camshaft-like central stalk that changes the conformation of three catalytic sites cyclically: one binds ADP and phosphate, one tightly binds and synthesizes ATP, one releases ATP.

With each rotation, three ATP molecules are produced. About 10 protons flow through per rotation (in mammals), so roughly 3 protons per ATP.

The numbers are staggering. A single ATP synthase can produce up to 600 ATP molecules per second. Your body contains an estimated 10^14 (100 trillion) mitochondria, each with thousands of ATP synthase complexes. The manufacturing capacity is astronomical.

ATP synthase is evolution's finest machine. A rotary engine at the nanometer scale, running on proton flow, producing the fuel that powers all complex life.

Efficiency

How efficient is this process?

In theory, the complete oxidation of one glucose molecule through glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation can yield about 30-32 ATP molecules. (Older textbooks say 36-38, but more accurate measurements revised this downward.)

The energy content of glucose is about 686 kilocalories per mole. If each ATP captures about 7.3 kcal (under standard conditions), then 32 ATP would capture about 234 kcal—roughly 34% efficiency.

That sounds modest, but compare it to alternatives:

- A car engine is about 20-25% efficient - A coal power plant is about 33-40% efficient - Solar panels are about 15-20% efficient

Mitochondria are competitive with industrial technology, operating at the nanometer scale, at body temperature, using proteins as machinery. And the actual cellular efficiency may be higher—under physiological conditions, ATP hydrolysis releases more energy than the standard 7.3 kcal.

Your cells run on one of the most efficient engines in the known universe.

Glycolysis: The Cytoplasmic Prelude

Before mitochondria get involved, glucose first undergoes glycolysis in the cytoplasm.

Glycolysis splits one glucose (6 carbons) into two pyruvate (3 carbons each). It yields a small amount of ATP directly (net 2 ATP) and some NADH. No oxygen required—glycolysis is anaerobic.

In the absence of oxygen, pyruvate gets converted to lactate (in animals) or ethanol (in yeast), regenerating NAD+ so glycolysis can continue. This is fermentation—the backup system when oxygen isn't available.

But fermentation is inefficient. You only get 2 ATP per glucose. The remaining energy in pyruvate is wasted.

With oxygen available, pyruvate enters mitochondria, gets converted to acetyl-CoA, and feeds into the citric acid cycle, ultimately yielding much more ATP through oxidative phosphorylation.

Glycolysis is the ancient core—the pathway all life shares. Oxidative phosphorylation is the upgrade that mitochondria brought.

Why Oxygen?

Oxygen is the terminal electron acceptor in the electron transport chain. But why oxygen?

The answer is chemistry. Oxygen is highly electronegative—it really wants electrons. This makes it an excellent electron sink, pulling electrons through the transport chain with considerable force. The greater the electronegativity difference between the start and end of the chain, the more energy can be extracted.

Other molecules can serve as electron acceptors—nitrate, sulfate, iron compounds—and some bacteria use them. But nothing matches oxygen's electron-pulling power. Oxygen-based respiration extracts the maximum energy from food.

There's a cost. Oxygen is reactive. The same property that makes it a good electron acceptor makes it dangerous. Partially reduced oxygen species—superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical—are the infamous reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage DNA, proteins, and lipids.

Mitochondria produce ROS as a byproduct of respiration. This is unavoidable. The electron transport chain occasionally leaks electrons directly to oxygen, producing superoxide instead of water. Cells have antioxidant defenses, but they're not perfect. Oxidative damage accumulates.

Oxygen is power and poison simultaneously. You can't have mitochondrial efficiency without oxidative risk.

The Warburg Observation

In the 1920s, Otto Warburg noticed something strange about cancer cells.

Even in the presence of oxygen, cancer cells preferentially ferment glucose to lactate rather than fully oxidizing it in mitochondria. They produce less ATP per glucose but consume glucose voraciously. This is the Warburg effect—aerobic glycolysis.

For decades, this was interpreted as mitochondrial dysfunction. Cancer cells have broken mitochondria, so they can't do oxidative phosphorylation properly, so they fall back on glycolysis. Makes sense, right?

Except it's not that simple. Many cancer cells have functional mitochondria. They choose glycolysis even when oxidative phosphorylation is available.

Why? Current thinking emphasizes biosynthesis. Rapidly dividing cells need more than just ATP. They need raw materials—nucleotides, amino acids, lipids—to build new cells. Glycolytic intermediates feed into biosynthetic pathways. By running lots of glucose through glycolysis and siphoning off intermediates, cancer cells fuel their rapid proliferation.

We'll explore this more in the Warburg Effect article later in this series.

ATP Beyond Energy

ATP does more than just provide energy. It's also a signaling molecule.

Extracellular ATP acts on purinergic receptors, transmitting signals between cells. It's involved in neurotransmission, inflammation, and cell death. When cells are damaged and release ATP, it's a "danger signal" that activates immune responses.

Inside cells, ATP concentration itself carries information. When ATP is abundant, the cell is healthy and energized. When ATP drops, stress responses activate. The AMP/ATP ratio is sensed by AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase), a master regulator that adjusts metabolism based on energy status.

ATP also contributes phosphate groups for phosphorylation—one of the most common post-translational modifications, regulating protein activity throughout the cell.

ATP isn't just fuel. It's a status indicator, a signaling molecule, and a regulatory input.

The Dance of Synthesis and Consumption

The steady state of ATP in your body is a dynamic equilibrium.

At rest, you consume ATP at a certain rate. During exercise, the rate skyrockets—muscles need far more ATP to contract repeatedly. During intense exercise, ATP consumption can increase 100-fold.

How do mitochondria keep up?

Increased electron transport. More oxygen consumption, more proton pumping, more ATP synthesis. Exercise increases breathing and heart rate partly to deliver more oxygen to mitochondria.

Mitochondrial biogenesis. Training stimulates the production of more mitochondria. Endurance athletes have more mitochondria per muscle fiber than sedentary people. More mitochondria mean more manufacturing capacity.

Substrate availability. The citric acid cycle needs acetyl-CoA. During prolonged exercise, fat oxidation becomes increasingly important as glucose stores deplete. Mitochondria smoothly switch fuel sources.

The system is remarkably responsive. From rest to maximal exertion, your body adjusts ATP production to match demand, maintaining the ATP pool within a narrow range.

You don't feel ATP rising and falling. You feel the outputs: energy, fatigue, vitality. ATP is the invisible currency behind all of it.

The Coherence Connection

Let's tie this to the AToM framework.

ATP production is a coherence maintenance system. The cell needs to keep ATP levels within bounds—too low means energy crisis; too high wastes resources and may cause other problems. The elaborate regulation of oxidative phosphorylation, the feedback from AMP/ATP ratios, the signaling networks that adjust metabolism—all of this maintains metabolic coherence.

The proton gradient itself is a form of stored coherence. It's an ordered state, a maintained difference against which work can be done. When the gradient dissipates (if the membrane becomes leaky), ATP synthesis fails. The cell dies.

Life maintains coherence by continuously generating order from disorder—pumping protons, building gradients, paying the entropy cost with the energy released from food. ATP is both the product and the payment.

Further Reading

- Alberts, B., et al. (2015). Molecular Biology of the Cell, Chapter 14: Energy Conversion. Garland Science. - Nicholls, D. G., & Ferguson, S. J. (2013). Bioenergetics. Academic Press. - Walker, J. E. (2013). "The ATP synthase: the understood, the uncertain and the unknown." Biochemical Society Transactions. - Lane, N. (2015). The Vital Question, Chapter 3. W.W. Norton.

This is Part 2 of the Mitochondria Mythos series. Next: "Mitochondrial DNA: Your Other Genome."

Comments ()