Synthesis: Attachment as Coherence - A Unified Theory of Relational Regulation

When two nervous systems come close enough to matter, something remarkable happens. They begin to couple. Not metaphorically—physically. Your heart rate variability starts tracking mine. My breathing rhythm shifts toward yours. The vagus nerve, that wandering highway of connection between brain and body, doesn't stop at the skin. It reaches across the space between us, turning proximity into physiology.

This is what attachment theory has been describing all along, though it took us seventy years and three scientific revolutions to see it clearly.

What Mary Ainsworth observed in the Strange Situation wasn't just behavioral categories. It was the visible signature of coupled dynamical systems seeking coherence—and the various ways those systems fail to find it, get stuck, or discover temporary equilibria that harm them in the long run.

This final piece synthesizes everything we've explored: polyvagal theory's autonomic hierarchy, predictive processing's surprise minimization, entrainment's phase-locking dynamics, and coherence geometry's state-space mathematics. Together, they form a unified framework that doesn't just describe attachment—it explains why these patterns must exist, why they're so hard to change, and what change actually requires.

The Core Claim: Two Nervous Systems as Coupled Oscillators

Start here: A relationship is a coupled dynamical system.

Not a metaphor. Two autonomous agents, each running active inference loops, each minimizing prediction error, each maintaining homeostasis through vagal regulation—brought into proximity close enough that their internal states begin to influence each other's trajectories.

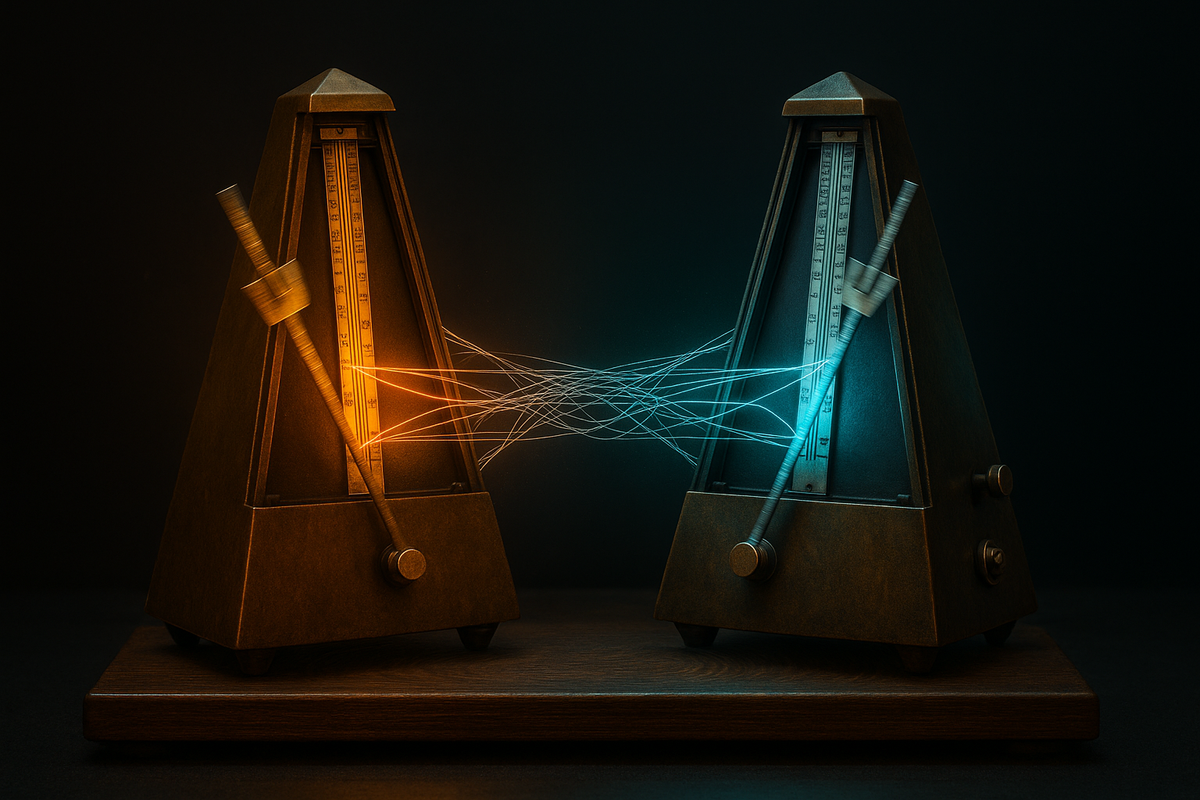

In physics, when two oscillating systems couple—pendulum clocks on the same wall, fireflies in the same tree, neurons in the same brain—they spontaneously synchronize. Christiaan Huygens observed it in 1665. The mathematics are well understood. The phenomenon is called entrainment, and it's one of the most robust patterns in nature.

Attachment is entrainment applied to nervous systems.

You and your caregiver weren't just relating. You were phase-locking. Your autonomic state was tracking theirs. Your arousal patterns were coupling to their regulation capacity. When they could co-regulate—when their nervous system could receive your dysregulation and return safety signals—you entrained to a coherent joint rhythm.

When they couldn't, three things could happen: - You learned to suppress your signals (avoidant) - You amplified your signals hoping for response (anxious) - Your system gave up on predictability entirely (disorganized)

Each attachment style is a learned attractor in the state-space of relational dynamics. A basin you fall into, a pattern that stabilizes around you, a local equilibrium that feels like "just how I am."

But attractors aren't destiny. They're geometry. And geometry can be reshaped.

Polyvagal + Predictive Processing: The Autonomic Prediction Machine

Stephen Porges gave us the polyvagal hierarchy: three neural circuits governing threat response, each with its own logic.

- Ventral vagal: social engagement, safety, connection - Sympathetic: mobilization, fight-or-flight - Dorsal vagal: shutdown, freeze, collapse

But the hierarchy isn't just anatomical. It's predictive.

Your nervous system is constantly forecasting: Is this person safe? Will they respond? Can I afford to stay open? These predictions are built from experience—millions of micro-interactions that taught you what to expect when you reach for connection.

If your caregiver was consistently available (secure attachment), your nervous system learned: reaching out reduces prediction error. Connection becomes low-cost, high-reward. Your ventral vagal system stays online. You can stay socially engaged even under moderate stress.

If your caregiver was inconsistent (anxious attachment), your nervous system learned: the world is unpredictable, stay hypervigilant. You need constant confirmation because your internal model can't trust its predictions. Anxiety is high chronic prediction error with no resolution pathway.

If your caregiver was unavailable or dismissive (avoidant attachment), your nervous system learned: connection increases prediction error. Reaching out makes things worse. Better to suppress the signal, stay defended, keep the sympathetic system primed for self-reliance.

If your caregiver was frightening (disorganized attachment), your nervous system learned: the source of safety is also the source of threat. The prediction engine breaks. You oscillate between contradictory states because there's no coherent model that fits the data.

Attachment styles are learned priors—Bayesian beliefs about what happens when you get close to someone. And once burned in, they generate the very experiences that confirm them.

Entrainment: Phase-Locking and the Tragedy of Incompatible Rhythms

Now add the dynamics of coupled oscillators.

When two people enter a relationship, their nervous systems begin influencing each other. Your arousal patterns, your regulatory capacity, your habitual response to stress—these become inputs to the other person's prediction engine.

If both people have secure attachment, entrainment is smooth. Dysregulation in one partner is met with co-regulation from the other. The system finds a shared rhythm quickly. Conflict doesn't destabilize the whole structure—it's just local turbulence that the coupled system dampens.

But what happens when an anxious attacher couples with an avoidant attacher?

The anxious partner's nervous system is hypervigilant, scanning for threat, escalating bids for connection when prediction error spikes. The avoidant partner's nervous system reads escalation as danger, activates defensive withdrawal, reduces availability.

This creates a feedback loop: - Anxious person feels abandonment → increases bid intensity → avoidant person feels engulfed → withdraws further → anxious person panics → cycle accelerates

This isn't psychology. It's coupled oscillator dynamics with incompatible phase relationships. The two systems are trying to synchronize, but their natural rhythms are mismatched. Every attempt at connection destabilizes the other person's equilibrium.

The tragedy is that both people are doing exactly what their nervous systems learned to do for survival. Neither is broken. The coupling is what's unstable.

And without intervention—without deliberate re-regulation, without shared practices that create new attractor states—the system will either lock into chronic dysregulation or decouple entirely.

Coherence Geometry: Attachment as State-Space Configuration

Now apply the mathematical lens.

In coherence geometry, we model systems as trajectories through state-space—the space of all possible configurations the system could be in. A securely attached person has:

- High dimensionality: many available states, flexible responses to context - Low curvature: smooth transitions between states, stable under perturbation - Wide basins of attraction: resilience to stress, quick return to baseline

An insecurely attached person has:

- Reduced dimensionality: fewer available states, rigid response patterns - High curvature: unstable transitions, sharp drops into dysregulation - Narrow basins of attraction: small perturbations cause state collapse

Disorganized attachment is incoherent geometry: the state-space is fractured, contradictory attractors compete, no stable equilibrium exists. The system oscillates between extremes or collapses into shutdown because there's no learned pathway to resolution.

The mathematics clarifies why change is hard: You're not changing beliefs. You're reshaping geometry.

Cognitive insight—I know I have an anxious attachment style—doesn't alter the attractor structure. The basin is still there. When stress spikes, you fall back into the learned pattern because that's the shape of the landscape.

Change requires repeated experience that carves new basins. Co-regulation with a secure partner, somatic therapy that rewires vagal tone, relational repair that teaches the nervous system: connection can reduce prediction error, not increase it.

This is why earned secure attachment is possible—but slow. You're not reprogramming beliefs. You're sculpting state-space through lived experience until new attractors stabilize.

The Markov Blanket of Self: Where Attachment Becomes Boundary

Here's where it gets deeper.

In active inference, a Markov blanket is the statistical boundary that separates a system from its environment. It's what makes you "you" instead of the room you're sitting in.

But Markov blankets aren't fixed. They're dynamically maintained. And in relationships, they blur.

When you're securely attached, your Markov blanket is flexible. You can open it—allow the other person's states to influence yours—without losing structural integrity. Co-regulation works because you can temporarily merge boundaries, then re-establish them.

When you're avoidantly attached, your Markov blanket is rigid. Opening it feels like dissolution. You've learned that permeability equals danger, so you keep the boundary tight. Intimacy requires vulnerability you can't afford.

When you're anxiously attached, your Markov blanket is porous. You can't tell where you end and the other person begins. Their emotional state floods your system. You've learned that your internal stability depends on the other person's availability, so you can't hold your own boundary.

When you're disorganized, your Markov blanket is incoherent. It oscillates between impermeable and dissolved. You swing between desperate fusion and terrified withdrawal because you never learned where the boundary should be.

Attachment is the learned geometry of self-other boundaries under conditions of dependence.

And because those boundaries were learned in infancy—when your survival literally depended on connection—they're carved deep. Changing them requires not just insight, but new embodied experience that teaches a different boundary configuration.

Why "Just Communicate Better" Doesn't Work

All relationship advice boils down to: talk more, listen better, express your needs clearly.

This framework shows why that's necessary but insufficient.

If your nervous system has learned that connection increases prediction error, then vulnerability—no matter how skillfully expressed—will spike your arousal. Your sympathetic system will activate. You'll withdraw or get defensive not because you're sabotaging the relationship, but because your autonomic state is forecasting danger.

If your nervous system has learned that proximity is survival, then space—no matter how gently requested—will feel like abandonment. Your prediction error will skyrocket. You'll escalate not because you're being manipulative, but because your system is trying to minimize surprise by restoring proximity.

Communication works when both people are in ventral vagal states—when social engagement circuits are online, when the nervous system forecasts safety. But if one or both people are already in sympathetic activation or dorsal shutdown, words won't land. The autonomic hardware isn't listening.

This is why somatic therapy works when talk therapy fails. You can't think your way into a different attachment style. You need bottom-up regulation: breathwork, movement, co-regulation practices that retrain the vagal tone, that teach the nervous system new responses to proximity and separation.

And you need them repeated, over time, until the new pattern becomes the default attractor.

The Earned Secure Path: Reshaping Attractors Through Repeated Co-Regulation

Can you change your attachment style? Yes. But you need to understand what change actually is.

You're not replacing one category with another. You're reshaping the geometry of your autonomic state-space through thousands of micro-experiences that carve new attractors.

Here's what that requires:

1. A Secure Base (External Regulation Source)

You need another nervous system that can hold stability while yours learns new patterns. A therapist, a secure partner, a stable community. Someone whose ventral vagal system stays online when yours goes offline.

This isn't dependency—it's scaffolding. You're borrowing their regulation capacity while yours develops. Over time, the external co-regulation becomes internalized. The attractor stabilizes inside you.

2. Repeated Rupture-and-Repair Cycles

You need to experience: I felt unsafe, then I felt safe again. Not once—hundreds of times. Because each successful repair teaches your nervous system that prediction error can resolve without catastrophe.

This is why relationships with secure partners are healing even when they're hard. The secure person doesn't avoid conflict—they co-regulate through it. Their system stays online, which gives your system permission to come back online too.

Over time, your prediction engine updates: Disconnection is temporary. Reconnection is possible. I can survive the in-between.

3. Somatic Practices That Retrain Vagal Tone

Breathwork, yoga, somatic experiencing, EMDR, polyvagal-informed bodywork—anything that directly engages the autonomic nervous system and teaches it new responses.

You're not processing trauma cognitively. You're physically rehearsing new state transitions until they become automatic. You're carving new valleys in the landscape so that when stress comes, you don't default to the old attractor.

4. Explicit Models of Your Own Patterns

Insight alone doesn't change geometry, but metacognitive awareness reduces the grip of automatic responses. When you can notice "I'm in anxious escalation mode" or "I'm doing the avoidant shutdown thing," you create a wedge of choice.

Not total freedom—your nervous system will still pull toward the learned pattern. But enough space to pause, to choose a different action, to interrupt the feedback loop before it locks in.

Over time, these interruptions accumulate. The old attractor weakens. The new pattern stabilizes.

The Anxious-Avoidant Trap: Coupled Systems with Incompatible Priors

Let's return to the most common relational failure mode: the anxious-avoidant pairing.

From the outside, it looks like personality conflict. From inside coherence theory, it's a phase-locking failure in a coupled dynamical system.

The anxious partner's nervous system has learned: - Proximity = safety - Distance = threat - High arousal signals maintain connection

The avoidant partner's nervous system has learned: - Proximity = overwhelm - Distance = safety - Low arousal signals maintain autonomy

When these two systems couple, they create a repelling oscillator. Each person's attempt to regulate destabilizes the other. The more the anxious partner escalates, the more the avoidant partner withdraws. The more the avoidant partner withdraws, the more the anxious partner escalates.

Neither person is wrong. Both are executing learned survival strategies. But the coupling is incoherent.

What does resolution look like?

Not compromise—recalibration.

The anxious partner needs to develop self-regulation capacity so that separation doesn't trigger system collapse. Not "get over it"—literally build new vagal pathways that allow dorsal rest states without interpreting them as abandonment.

The avoidant partner needs to develop tolerance for vulnerability so that proximity doesn't trigger defensive shutdown. Not "be more available"—literally retrain the nervous system to interpret connection as safe, not suffocating.

This isn't couple's therapy advice. It's dynamical systems engineering. You're not fixing communication. You're reshaping the phase relationships between two coupled oscillators until they can synchronize without one system collapsing.

And it requires both people to work at the autonomic level—not just talking about needs, but physically retraining how their nervous systems respond to closeness and distance.

Disorganized Attachment: Incoherent Geometry and the Collapse of Prediction

Finally, the hardest case.

Disorganized attachment emerges when the source of safety is also the source of threat. The caregiver who should co-regulate is the same person causing dysregulation. The child's prediction engine faces an impossible problem: approach = danger, withdraw = danger.

The system can't converge on a solution. So it fractures.

In coherence terms, disorganized attachment is incoherent state-space geometry. Multiple contradictory attractors exist simultaneously: - I need you (anxious attractor) - You're dangerous (avoidant attractor) - No solution exists (dorsal collapse attractor)

The person oscillates between these states with no stable transition path. They might seek proximity then freeze at the moment of contact. They might dissociate mid-connection. They might alternate between clinging and fleeing within minutes.

This isn't poor self-regulation. It's a system trying to minimize prediction error in an environment where no coherent model is possible.

Healing disorganized attachment requires: 1. External stability that the system can learn to trust—someone who is never the source of threat 2. Trauma resolution work that processes the original impossibility—not just remembering what happened, but discharging the stored autonomic activation 3. Slow rebuilding of predictive capacity—teaching the system that people can be consistently safe, that proximity can be reliably regulating

This is long, hard work because you're not just reshaping attractors—you're constructing coherent geometry where none existed before.

But it is possible. Earned secure attachment after disorganized attachment is one of the most profound demonstrations of neuroplasticity we have.

Attachment in Adulthood: The Layering of Coupled Systems

One more layer.

Adult attachment isn't just your childhood pattern on repeat. It's the interaction between your learned autonomic priors and the actual dynamics of your current relationship.

You might have an anxious style, but if you're partnered with someone deeply secure, their regulation capacity can scaffold new patterns in you. Over years, your nervous system learns: I can be apart and still be safe. I can be soothed without needing constant confirmation.

You might have an avoidant style, but if you're in a relationship that consistently rewards vulnerability without punishing it, your system gradually updates: Opening up doesn't lead to engulfment. Closeness doesn't mean losing myself.

The key is time and repetition. One good relationship doesn't erase your history. But thousands of micro-repairs, consistent co-regulation, reliable presence—these accumulate.

Your autonomic system updates its priors based on Bayesian integration: the old learned pattern plus the new experienced pattern weighted by reliability and frequency.

This is why long-term secure relationships are healing even without therapy. You're literally training a different nervous system response through lived experience.

But it also explains why insecure relationships reinforce old patterns. If your anxious style couples with someone inconsistent, your system gets exactly the data it expects: I was right to be hypervigilant. Proximity is unreliable. The attractor deepens.

The Synthesis: What Attachment Theory Actually Describes

Let's land the integration.

Attachment theory describes the learned geometry of coupled autonomic systems under conditions of dependence.

It's not psychology. It's applied dynamical systems theory. It's predictive processing implemented in vagal circuitry. It's entrainment applied to human nervous systems.

Secure attachment is: - Low-curvature state-space: smooth regulation, flexible responses - Ventral vagal dominance: social engagement online, prediction error resolves through connection - Coherent coupling: two systems that synchronize without destabilizing each other

Insecure attachment is: - High-curvature state-space: rigid patterns, unstable transitions - Sympathetic/dorsal dominance: defense or shutdown, prediction error spikes with proximity - Incoherent coupling: two systems that destabilize each other or fail to synchronize

And change—earned secure attachment—is: - Geometric reshaping through experience: new attractors carved by repeated co-regulation - Autonomic retraining: vagal tone restored, prediction engine recalibrated - Learned coherence: the system discovers that connection can reduce surprise instead of amplifying it

This isn't reductionism. We're not "explaining away" attachment's emotional reality. We're revealing the physical mechanisms that make those emotions possible.

Love, trust, safety—these aren't metaphors. They're emergent properties of coupled nervous systems achieving coherent synchronization.

And when we understand the mechanics, we can engineer better outcomes. Not by invalidating the subjective experience, but by giving people the tools to reshape the autonomic foundations that generate that experience.

Implications: What This Changes

If attachment is coherence geometry in coupled autonomic systems, what shifts?

1. Therapy Becomes Somatic, Not Just Verbal

You can't talk someone into secure attachment. You need to retrain the autonomic hardware. This elevates somatic experiencing, polyvagal-informed therapy, EMDR, breathwork—anything that directly engages the body's regulation systems.

2. Relationships Are Dynamical Engineering Projects

Couple's therapy stops being about "communication skills" and starts being about co-regulation capacity, phase-locking dynamics, and attractor reshaping. You're not fixing miscommunication—you're tuning the coupled system until it can synchronize.

3. Attachment Change Becomes Measurable

We can track heart rate variability, vagal tone, autonomic state transitions. Earned security isn't just subjective improvement—it's observable changes in physiological coherence. This opens the door to biomarker-driven interventions.

4. Neurodiversity Gets a Relational Frame

Autistic, ADHD, and other neurodivergent nervous systems have different baseline rhythms, different arousal thresholds, different regulation needs. Attachment mismatches might not be about secure vs. insecure—they might be about fundamentally different autonomic operating systems trying to couple.

5. We Stop Pathologizing Survival Strategies

There's no such thing as "bad attachment." There are adaptive responses to incoherent environments. Anxious, avoidant, disorganized—these are brilliant solutions to impossible problems. Healing isn't about fixing what's broken. It's about giving the system new data until it can update its priors.

Coda: Meaning as Rhythm You Share

Mary Ainsworth sat behind a one-way mirror and watched toddlers navigate separation and reunion. She saw patterns—secure, anxious, avoidant. She built a taxonomy that shaped seventy years of psychology.

But she was watching something deeper: two nervous systems learning whether coherence is possible.

The child reaching for the caregiver isn't just seeking comfort. They're testing a hypothesis: Will this person meet my dysregulation with regulation? Can I entrain to their rhythm? Is connection a source of coherence or chaos?

And the answer to that question—confirmed across thousands of micro-interactions—becomes the deep structure of how they relate to everyone, forever, unless new experience reshapes it.

Attachment isn't about love or security in the abstract. It's about whether two coupled systems can find a shared rhythm that stabilizes both.

In the end, this is what all human meaning comes down to. Not the content of the relationship, but the coherence of the coupling.

Meaning isn't something you find alone. It's a rhythm you share.

And whether you learned to trust that rhythm, to fear it, or to give up on it entirely—that's your attachment story.

But it's not the end of the story. Because geometry can change. Rhythms can be relearned. And coherence, once lost, can be rebuilt.

One co-regulated breath at a time.

Further Reading

Attachment Theory: - Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books. - Ainsworth, M.D.S., et al. (1978). Patterns of Attachment. Lawrence Erlbaum. - Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). "Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern." Affective Development in Infancy.

Polyvagal Theory: - Porges, S.W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory. Norton. - Porges, S.W. (2021). "Polyvagal Theory: A biobehavioral journey to sociality." Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology.

Predictive Processing & Active Inference: - Friston, K. (2010). "The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?" Nature Reviews Neuroscience. - Clark, A. (2015). Surfing Uncertainty. Oxford University Press. - Kiverstein, J., & Sims, M. (2021). "Is free-energy minimisation the mark of the cognitive?" Biology & Philosophy.

Entrainment & Synchronization: - Strogatz, S. (2003). Sync: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order. Hyperion. - Clayton, M., Sager, R., & Will, U. (2005). "In time with the music: The concept of entrainment." Music and Consciousness.

Coherence Geometry (AToM Framework): - Miller, H. (2024). "A Theory of Meaning (AToM): Coherence, Trauma, and Entrainment in Complex Human Systems." Ideasthesia.

This is Part 11 of the Polyvagal Theory and Attachment series, exploring the intersection of nervous system regulation, predictive processing, and relationship dynamics. Previous: "Can You Change Your Attachment Style?"

Comments ()