What Is Attachment Theory? Bowlby, Ainsworth, and the Science of Connection

Attachment theory is a psychological framework developed by John Bowlby that explains how early bonds between infants and caregivers shape emotional development and relationship patterns across the lifespan. Bowlby's attachment theory proposes that human infants are biologically programmed to form attachments with caregivers as a survival mechanism—connection isn't about sentiment, it's about staying alive.

In the 1950s, Bowlby did something controversial for his time: he took mothers seriously. Not as abstract Freudian symbols or sources of neurotic fixation, but as actual biological regulators of infant survival. He noticed that children separated from their mothers—evacuated during the London Blitz, hospitalized, orphaned—didn't just miss them emotionally. They showed a predictable, three-stage physiological breakdown: protest (crying, searching), despair (withdrawal, passivity), and finally detachment (apparent indifference, even when reunited).

This wasn't psychology. It was biology.

Bowlby's insight was simple but radical: attachment isn't about love as sentiment. It's about survival as biological imperative. An infant mammal that fails to maintain proximity to its caregiver dies. Natural selection built attachment into our nervous systems the way it built hunger, thirst, and pain—as non-negotiable survival signals.

This put him at odds with virtually everyone. Psychoanalysts thought he was reducing the mother to a mere feeding apparatus. Behaviorists thought he was being too mentalistic, too evolutionary, too European. Even his own colleagues at the Tavistock Clinic were skeptical. But Bowlby had data—observations of institutionalized children, war orphans, hospitalized infants—and the data were undeniable.

He also had an intellectual ally in an unexpected place: ethology, the study of animal behavior. Harry Harlow's experiments with rhesus monkeys were showing that infant monkeys preferred a soft cloth surrogate mother over a wire mother that dispensed food. The drive for contact comfort wasn't about feeding. It was something older, deeper, more fundamental. Konrad Lorenz's work on imprinting in birds showed that attachment didn't require learning in the traditional sense—it was a developmental program that ran on a biological clock.

Bowlby synthesized these threads into a single claim: humans have an evolved attachment behavioral system that serves the function of proximity maintenance. When threat is detected, the system activates. The infant cries, clings, follows, protests separation. When the caregiver responds and proximity is restored, the system deactivates. The infant calms, explores, plays.

The question wasn't whether attachment existed. The question was how it worked—and what happened when it didn't.

The Strange Situation: A Two-Minute Window Into Lifelong Patterns

The Ainsworth Strange Situation is a laboratory procedure developed by Mary Ainsworth in the 1970s to measure infant attachment patterns through a series of separations and reunions with the caregiver. Mary Ainsworth, a developmental psychologist who took Bowlby's theory and turned it into something measurable, designed what would become the most influential laboratory procedure in developmental psychology.

The protocol is deceptively simple:

1. A mother and infant (12-18 months old) enter an unfamiliar room with toys 2. A stranger enters 3. The mother leaves the infant with the stranger 4. The mother returns 5. The mother leaves again, infant is alone 6. The stranger returns 7. The mother returns for a final reunion

The whole thing takes about 20 minutes. What Ainsworth measured wasn't whether the infant got upset when the mother left—of course they did. What mattered was how the infant behaved when the mother returned.

That two-minute reunion window revealed patterns that predicted relationship behavior decades later.

The Four Patterns: How Infants Organize Around Uncertainty

Attachment theory identifies four primary attachment styles: secure, anxious-ambivalent, avoidant, and disorganized, each representing a distinct pattern of how infants respond to separation from and reunion with their caregiver. Ainsworth originally identified three patterns. A fourth was added later by Mary Main. Here's what they saw:

Secure Attachment (B)

Reunion behavior: Infant is distressed by separation, seeks contact immediately upon reunion, is soothed relatively quickly, then returns to play.

The pattern: Separation = stress signal → caregiver returns → stress is resolved → system recalibrates. The infant uses the caregiver as a secure base for exploration and a safe haven in distress. Ainsworth found this in about 60-65% of middle-class American samples.

What it means: The infant has learned that distress signals reliably bring relief. Predictability is encoded.

Anxious-Ambivalent Attachment (C)

Reunion behavior: Infant is intensely distressed by separation, seeks contact desperately but cannot be soothed. Shows anger, resistance, clinging—pushes away while simultaneously demanding closeness. Can't return to play.

The pattern: Separation = catastrophic threat → caregiver returns but relief doesn't come → the system stays activated, cycling between rage and desperation.

What it means: The infant has learned that the caregiver is inconsistently available. Sometimes responsive, sometimes not. The system stays vigilant, hyperactivated, scanning constantly for signs of abandonment.

Avoidant Attachment (A)

Reunion behavior: Infant shows minimal distress during separation. Upon reunion, actively avoids the caregiver—turns away, focuses on toys, acts indifferent. If picked up, may stiffen or lean away.

The pattern: Separation happens → infant appears unbothered → reunion happens → infant ignores caregiver.

But here's the key finding: Ainsworth measured cortisol (stress hormone). Avoidant infants showed the same physiological stress as anxious infants during separation. They just didn't show it behaviorally.

What it means: The infant has learned that expressing distress makes things worse or gets no response. The solution is to deactivate the attachment system—to shut down the outward signal while the internal stress remains.

Disorganized Attachment (D)

Reunion behavior: No coherent strategy. Contradictory behaviors—approaches then freezes, seeks contact then darts away, blank staring, confused expressions. Sometimes shows fear of the caregiver.

The pattern: No pattern. The system tries to run incompatible programs simultaneously.

What it means: The caregiver is both the source of distress and the solution to distress. Main called this "fright without solution." The infant has no organizing strategy because the two fundamental imperatives—seek safety, avoid danger—are in direct contradiction. Often seen in cases of abuse, frightening caregiver behavior, or severe trauma.

Why This Matters: The Internal Working Model

Internal working models are cognitive-affective schemas proposed by Bowlby that encode an individual's expectations about themselves, others, and relationships based on early attachment experiences. Bowlby didn't just describe behavior. He proposed a mechanism that explains how early patterns persist across the lifespan.

An infant with a secure attachment develops a model that says: - I am worthy of care - Others are reliable - Distress can be managed - The world is navigable

An infant with an anxious attachment develops a model that says: - I am not enough to hold others' attention - Others are unpredictable - Distress might spiral out of control - I must work hard to maintain connection

An infant with an avoidant attachment develops a model that says: - I must handle things alone - Others won't help or might make things worse - Distress is dangerous to express - Independence is safety

An infant with disorganized attachment develops models that contradict each other or fragment entirely.

These aren't conscious beliefs. They're implicit predictions that shape behavior automatically, outside awareness.

And here's the critical part: these models are stable over time. Studies tracking people from infancy into adulthood show that attachment patterns assessed in the Strange Situation at 12 months predict romantic relationship behavior at 20 years old with significant accuracy (Main et al., 1985; Waters et al., 2000). Not perfectly—development isn't deterministic—but the correlation is striking.

How Attachment Spreads: From Infancy to Romance

Adult attachment theory applies Bowlby and Ainsworth's infant attachment patterns to romantic relationships, showing that the same secure, anxious, and avoidant styles persist from childhood into adult partnerships. The beauty and terror of attachment theory is how the same patterns show up across the lifespan.

In the 1980s, researchers Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver had a simple but brilliant idea: what if adult romantic love was an attachment process, not fundamentally different from infant-caregiver attachment? They adapted Ainsworth's categories to adult relationships and found nearly identical distributions. About 60% of adults described themselves as secure in romantic relationships, roughly 20% as anxious, 20% as avoidant.

The patterns looked like this:

An anxious adult partner: - Constantly monitors for signs of rejection - Interprets ambiguity as abandonment - Protests separation intensely - Can't be easily soothed by reassurance - Needs frequent validation and closeness - Fears being alone more than being in a bad relationship

An avoidant adult partner: - Emphasizes independence, downplays need - Uncomfortable with intimacy and emotional vulnerability - Distances when things get close - Self-sufficient to a fault - Values freedom more than connection - Fears being trapped more than being alone

A secure adult partner: - Comfortable with both intimacy and autonomy - Communicates needs directly - Trusts others and is trustworthy - Manages conflict without catastrophizing or withdrawing - Can be alone without feeling abandoned - Can be close without feeling engulfed

The parallels are not metaphorical. They're structural. The same dynamics that organize infant behavior around an unpredictable caregiver organize adult behavior around an unpredictable romantic partner. The protest, despair, and detachment sequence Bowlby observed in separated infants? It's the same sequence that plays out when an adult experiences romantic rejection or abandonment.

Ainsworth's genius was showing that these patterns aren't personality types. They're relational strategies shaped by experience with specific others. A person can be secure with one partner and anxious with another. The pattern emerges from the interaction, not from a fixed trait. You carry forward a default strategy learned in infancy, but that strategy is always context-dependent, always updating based on new relational data.

This is why the same person might feel secure with friends but anxious in romance, or avoidant with parents but secure with a long-term partner. The attachment system is domain-specific and relationship-specific, not a global personality variable.

The Question Everyone Asks: Can You Change Your Attachment Style?

Attachment styles can change through long-term secure relationships, effective therapy, and corrective relational experiences—a phenomenon researchers call "earned security." Short answer: yes, with caveats.

Attachment patterns are stable but not immutable. Major findings:

Earned security is real. Adults who report insecure childhoods but test as secure in adulthood exist and are studied extensively. What changed? Usually: long-term relationships with secure partners, effective therapy, or significant corrective relational experiences.

Attachment fluctuates with context. Stress, relationship quality, major life events (loss, trauma, childbirth) can shift attachment security up or down. Security is best thought of as a state with trait-like stability rather than a fixed essence.

Insight helps, but isn't sufficient. Knowing your attachment pattern doesn't automatically change it. The internal working models are implicit—they run below conscious awareness, in the nervous system itself. Change requires new experiences that contradict old predictions, repeated over time until the system updates its model.

This is where attachment theory as traditionally understood hits a wall. It describes patterns brilliantly. It tracks them longitudinally. But it struggles to explain the mechanism of change at the level where the patterns are actually encoded.

The Missing Piece: What If Attachment Isn't Cognitive?

Polyvagal Theory proposes that attachment patterns are not just cognitive schemas but autonomic nervous system states—meaning secure, anxious, and avoidant attachment styles reflect different configurations of the vagal nerve system that regulates social connection and threat response. Here's the quiet revolution happening in attachment research right now: what if internal working models aren't primarily cognitive structures? What if they're autonomic nervous system states?

Stephen Porges' Polyvagal Theory offers a neurophysiological account of exactly what Bowlby and Ainsworth were observing. The patterns aren't mental schemas. They're nervous system strategies for managing threat and safety in the context of social connection.

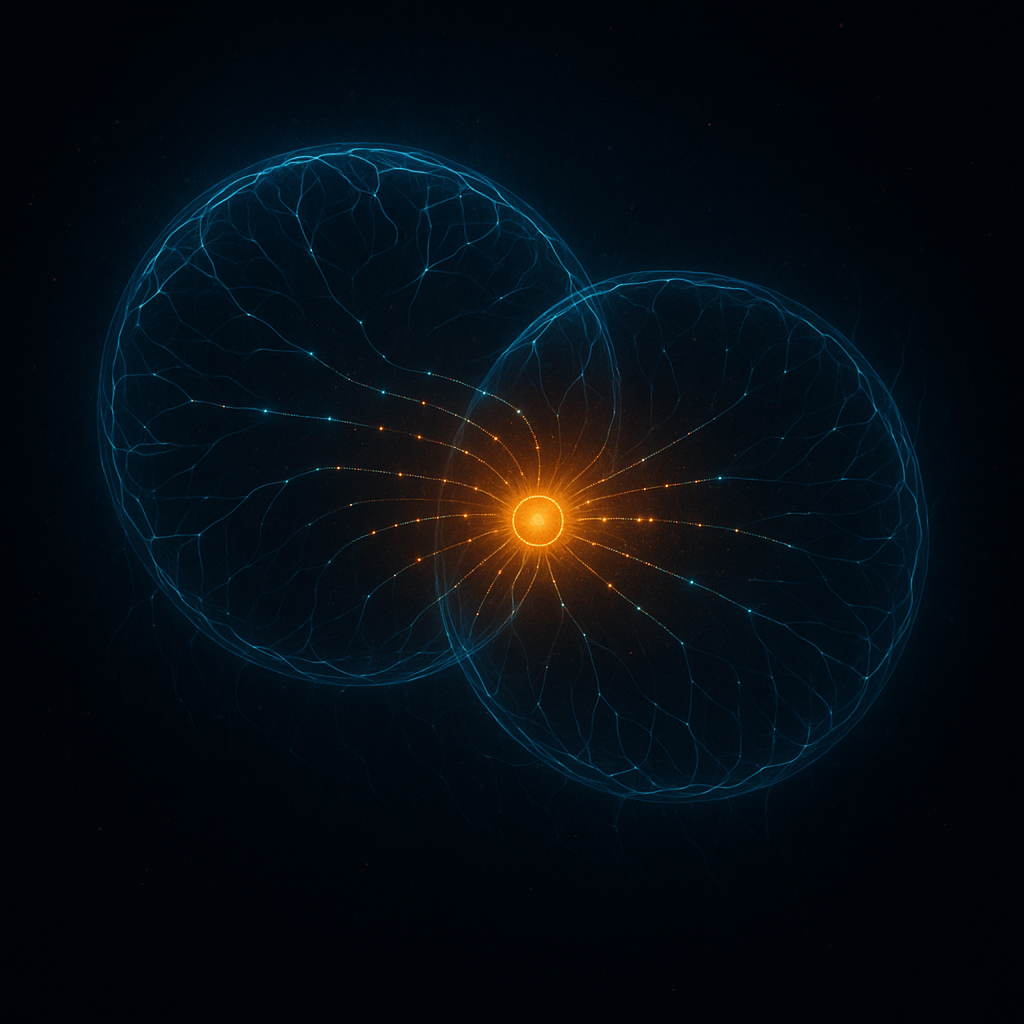

The polyvagal model describes three neural circuits, each with its own evolutionary history and functional role:

The ventral vagal system (newest, mammalian): Supports social engagement—facial expression, vocalization, listening, calm connection. When this system is online, you feel safe, present, capable of intimacy.

The sympathetic system (older, shared with all vertebrates): Mobilizes fight-or-flight responses. When activated, you're vigilant, activated, ready to act or defend.

The dorsal vagal system (oldest, shared with reptiles): Triggers immobilization, shutdown, collapse. When activated, you dissociate, freeze, go numb.

Now map this onto attachment patterns:

Secure attachment = ventral vagal dominance. A nervous system that can flexibly shift between calm engagement, playful mobilization, and return to baseline. When stressed, it activates sympathetically but can recruit ventral vagal regulation to return to calm. The system trusts that co-regulation is possible.

Anxious attachment = chronic sympathetic activation. A nervous system stuck in hypervigilance, constantly scanning for danger, unable to down-regulate. The sympathetic system is primed for threat detection—particularly threats to connection. Every ambiguous signal triggers a mobilization response.

Avoidant attachment = dorsal vagal shutdown layered over sympathetic arousal. A system that's learned to collapse into immobilization while maintaining an external appearance of functioning. The person looks calm but is physiologically collapsed, defended against connection by preemptive numbing.

Disorganized attachment = autonomic chaos. A system oscillating between incompatible states—sympathetic fight-or-flight and dorsal shutdown, with no coherent organizing principle. The ventral vagal system can't come online because the environment is both threatening (activates defense) and the source of safety (requires engagement). The system fragments.

This isn't a metaphor. The autonomic nervous system is the actual substrate where attachment patterns are encoded. The "internal working model" is the nervous system's prediction about what states are safe, which transitions are possible, and how other nervous systems will respond.

When Ainsworth measured cortisol in avoidant infants and found high stress despite behavioral calm, she was measuring the gap between autonomic state and behavioral display. When Main found that disorganized infants showed fear of the caregiver, she was identifying a system in autonomic conflict—the ventral vagal system trying to engage, the sympathetic system preparing to flee, the dorsal system pulling toward collapse.

The Strange Situation wasn't measuring attachment beliefs. It was measuring autonomic flexibility in the context of relational stress.

Why This Reframe Changes Everything

When attachment patterns are understood as autonomic nervous system patterns rather than purely cognitive beliefs, healing requires nervous system regulation techniques—somatic therapy, breathwork, and body-based interventions—rather than insight alone. If attachment patterns are nervous system patterns, then:

Change isn't about insight. It's about nervous system regulation. You can't think your way into secure attachment. You have to train your nervous system to tolerate new states—to stay ventral vagal in proximity, to down-regulate from sympathetic without collapsing into dorsal, to experience rupture and repair without fragmenting.

Attachment isn't about the past. It's about present-moment physiology. Yes, early experiences matter because they set the autonomic baseline. But the pattern you're experiencing right now is the state your nervous system is in right now. Change the state, change the pattern.

Relational dynamics are nervous system dynamics. An anxious-avoidant relationship isn't two people with incompatible beliefs. It's two nervous systems in frequency mismatch—one stuck in sympathetic overdrive, the other defended by dorsal shutdown. They're trying to co-regulate but running incompatible operating systems.

The body is the intervention. Therapy that changes attachment has to work at the autonomic level—somatic experiencing, sensorimotor psychotherapy, EMDR, even certain forms of yoga and breathwork. These aren't alternative modalities. They're the only modalities that target the actual substrate where attachment lives.

What Comes Next

This series will unpack the attachment patterns Ainsworth identified—anxious, avoidant, disorganized, secure—but through an autonomic lens. We'll look at what each pattern looks like in the nervous system, why it emerges, how it shows up in adult relationships, and most importantly, how it can change.

Attachment theory gave us the map. Polyvagal Theory gives us the mechanism. Together, they offer a complete account of how connection is built, broken, and rebuilt—at the level where it actually happens.

Not in beliefs. In the body.

Further Reading

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books. - Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Lawrence Erlbaum. - Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). "Discovery of an Insecure-Disorganized/Disoriented Attachment Pattern." In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective Development in Infancy. - Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. W. W. Norton. - Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., & Albersheim, L. (2000). "Attachment Security in Infancy and Early Adulthood: A Twenty-Year Longitudinal Study." Child Development, 71(3), 684-689.

This is Part 1 of the Polyvagal Attachment series, exploring how attachment patterns are encoded in the autonomic nervous system. Next: "Anxious Attachment Style: The Nervous System That Can't Stop Scanning."

Comments ()