Basis and Dimension: The Coordinates of Abstract Spaces

Coordinates aren't absolute. They depend on choosing a basis.

The vector (3, 4) in standard coordinates might be (5, -1) in some other coordinate system. Same vector. Different numbers.

Understanding this—that coordinates are choices, not facts—is essential to thinking clearly about linear algebra.

What a Basis Is

A basis for a vector space V is a set of vectors that:

- Spans V: Every vector in V can be written as a linear combination of basis vectors

- Is linearly independent: No basis vector can be written as a combination of the others

A basis is the minimal spanning set. No redundancy, complete coverage.

Coordinates Relative to a Basis

Once you choose a basis B = {v₁, v₂, ..., vₙ}, every vector w in V has a unique representation:

w = c₁v₁ + c₂v₂ + ... + cₙvₙ

The coefficients (c₁, c₂, ..., cₙ) are the coordinates of w relative to B.

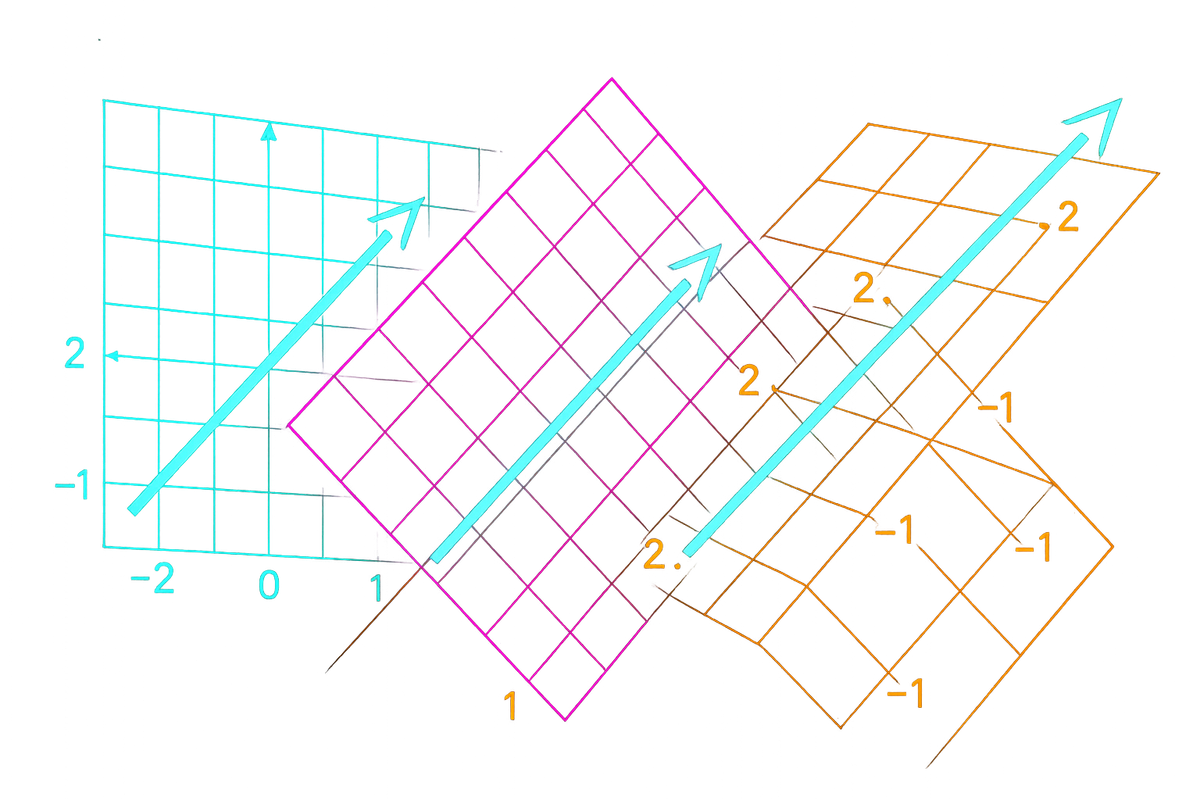

Different basis? Different coordinates. Same vector.

Example in ℝ²:

Standard basis: e₁ = (1,0), e₂ = (0,1). Vector w = (3, 4) has coordinates [3, 4]ₛₜₐₙdₐᵣd.

Alternative basis: b₁ = (1,1), b₂ = (1,-1). Same vector w = (3, 4) = 3.5(1,1) + (-0.5)(1,-1). Coordinates: [3.5, -0.5]ₐₗₜ.

Same arrow in the plane. Different numbers describing it.

Why Coordinates Aren't Fundamental

This is a shift in perspective.

In school, you're taught that (3, 4) is the vector. But (3, 4) is just a representation. The vector is an arrow pointing from origin to a point.

If you rotate your axes 45°, the same arrow has different numbers. The arrow didn't move—your description changed.

Coordinates are relative to a basis. The vector is absolute.

Dimension

The dimension of a vector space is the number of vectors in any basis.

Every basis of a given vector space has the same number of elements. This is a theorem, proved rigorously.

Examples:

- ℝⁿ has dimension n

- Polynomials of degree ≤ 3 have dimension 4 (basis: 1, x, x², x³)

- 2×3 matrices have dimension 6

- The space of solutions to y'' + y = 0 has dimension 2 (basis: sin(x), cos(x))

Dimension counts "independent directions"—how many degrees of freedom the space has.

Finding a Basis

To find a basis for a subspace:

- Take a spanning set (vectors that generate the subspace)

- Remove redundant vectors until independent

- What remains is a basis

Or:

- Start with the empty set

- Add vectors one at a time, keeping only those not in the span of previous vectors

- Stop when you span the space

For the column space of a matrix:

Row reduce to echelon form. The columns with pivots form a basis for the column space.

Change of Basis

If you have two bases B and B' for the same space, the change-of-basis matrix P converts coordinates from one to the other.

If [v]_B is the coordinate vector of v in basis B, and [v]_B' is in basis B':

[v]_B' = P⁻¹[v]_B

The columns of P are the old basis vectors expressed in the new basis coordinates.

Why Change Basis?

Some bases are better than others—depending on the problem.

Standard basis: Convenient for computation, familiar.

Eigenbasis: If a matrix A has a full set of eigenvectors, using them as basis makes A diagonal. Then powers of A are easy: just power the diagonal entries.

Orthonormal basis: Vectors perpendicular and unit length. Makes projections trivial. Dot product equals coordinate dot product.

Principal components: In data analysis, the eigenvectors of covariance matrix point along directions of maximum variance. Using them as basis reveals structure in data.

Choosing the right basis can turn a hard problem into an easy one.

The Same Transformation, Different Matrix

A linear transformation T: V → V has a matrix representation that depends on the choice of basis.

If A is the matrix of T in basis B, and P is the change-of-basis matrix from B to B':

A' = P⁻¹AP

is the matrix of T in basis B'.

Same transformation. Different matrix. Related by conjugation.

This is why eigenvalues are important: they're the same no matter what basis you use. They're intrinsic to the transformation.

Orthonormal Bases

An orthonormal basis has vectors that are:

- Orthogonal (perpendicular): vᵢ · vⱼ = 0 for i ≠ j

- Normalized (unit length): ||vᵢ|| = 1

With an orthonormal basis, coordinates become simple:

cᵢ = w · vᵢ

Just dot your vector with each basis vector. No solving systems.

Orthonormal bases make everything easier:

- Projections are dot products

- The change-of-basis matrix is its own inverse (P⁻¹ = Pᵀ)

- Numerical computations are more stable

Gram-Schmidt Process

You can turn any basis into an orthonormal one.

Start with basis {v₁, v₂, ..., vₙ}.

- u₁ = v₁ / ||v₁||

- u₂ = (v₂ - projection of v₂ onto u₁) / ||...||

- u₃ = (v₃ - projections onto u₁ and u₂) / ||...||

- Continue...

Each step removes the components along previous vectors, then normalizes.

The result is an orthonormal basis for the same space.

Dimension and Rank

For a linear transformation T: V → W:

- Rank of T = dim(im(T)) = dimension of the image

- Nullity of T = dim(ker(T)) = dimension of the kernel

Rank-Nullity Theorem: Rank + Nullity = dim(V)

For matrices:

- Rank = number of pivots in row echelon form

- Nullity = number of free variables = n - rank (for n×n matrix)

Dimension in Applications

Machine Learning: Data lives in high-dimensional space (one dimension per feature). But often it lies near a lower-dimensional subspace. PCA finds this subspace.

Signal Processing: Signals can be expanded in orthogonal bases (Fourier, wavelets). The dimension is infinite, but practical signals are approximated by finite sums.

Physics: Phase space of a system has dimension 2n for n particles (position and momentum for each). This determines the number of initial conditions needed.

Graphics: 3D space plus time = 4D. Homogeneous coordinates add a fifth dimension for convenience.

The Core Insight

Dimension is intrinsic—it doesn't depend on how you describe the space.

Coordinates are extrinsic—they depend on your choice of basis.

The power of linear algebra is that you can change coordinates to make problems easier, while dimension and other intrinsic properties stay fixed.

Choose your basis wisely. The same problem can be trivial or intractable depending on your coordinates.

This is Part 10 of the Linear Algebra series. Next: "Applications: Why Linear Algebra Runs the Modern World."

Part 10 of the Linear Algebra series.

Previous: Linear Transformations: Functions That Preserve Structure Next: Applications: Why Linear Algebra Runs the Modern World

Comments ()