Category Theory for People Who Hate Math (But Love Patterns)

Learn category theory as pattern recognition, not mathematics. Discover how identical structures repeat across psychology, relationships, and organizations.

Category Theory for People Who Hate Math (But Love Patterns)

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

You've noticed that certain patterns keep appearing.

The way a conversation spirals follows the same dynamic as the way your attention spirals. The structure of your family mirrors the structure of your workplace. The pattern that broke your last relationship is somehow the same pattern that breaks your creative projects.

You mention this to people and they nod politely. They think you're speaking metaphorically. Drawing loose analogies. Finding comforting resemblances in unrelated things.

You're not.

The patterns aren't similar. They're the same. The same abstract structure genuinely appearing in different contexts, wearing different costumes, instantiated in different materials. And there's a branch of mathematics dedicated to studying exactly this phenomenon—the phenomenon of structural identity across different manifestations.

Category theory is the mathematics of pattern itself. Where other mathematics studies particular structures—numbers, shapes, equations, probabilities—category theory steps back and asks: what is a pattern, such that it can appear unchanged in domains as different as algebra and topology, as distant as physics and psychology?

This matters for meaning because meaning has structure. The structure of coherence at one scale—neural, individual, relational, cultural—is not merely analogous to the structure at other scales. It's the same structure. Category theory gives us the vocabulary to say precisely what "the same" means, and precisely how structure survives the jump between domains.

What a Category Is

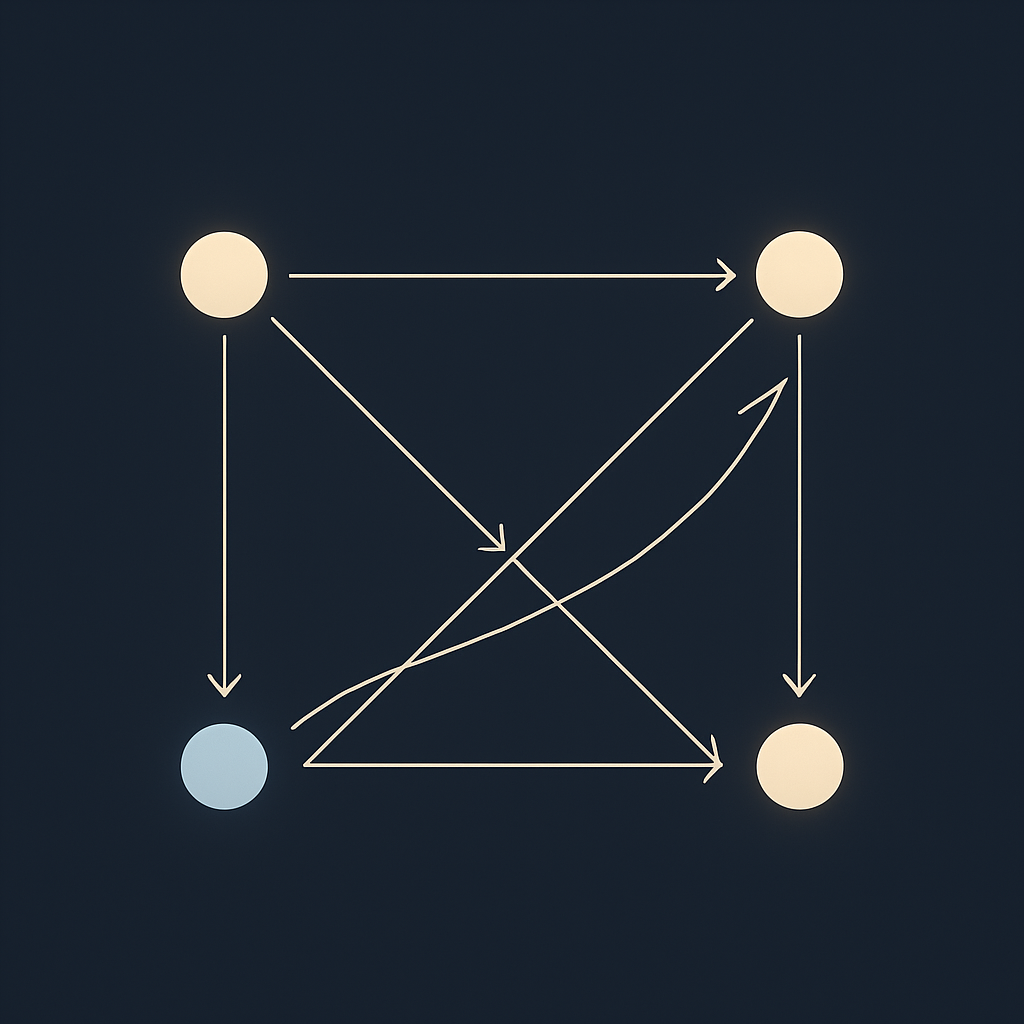

The formalism starts simple. Embarrassingly simple. A category consists of:

Objects. Things. Any things. Points, if you want to visualize them. They could be numbers, sets, spaces, states, people, organizations—the math doesn't specify and doesn't care what they are.

Arrows (morphisms). Connections between objects. If A and B are objects, an arrow f: A → B goes from A to B. Arrows represent relationships, transformations, processes—anything that connects one object to another.

Composition. If you have an arrow f: A → B and an arrow g: B → C, you can compose them to get an arrow g∘f: A → C. You can get from A to C by going through B.

Identity. For every object A, there's an identity arrow id_A: A → A. It's the arrow that goes from A to itself by doing nothing—by staying put.

That's it. Objects, arrows, composition, identity. The rules are minimal: composition is associative (doing f then g then h gives the same result regardless of how you group them), and identity arrows compose trivially (doing nothing and then doing something is the same as just doing something).

This seems too bare to be useful. There's no content here. We haven't said what objects are made of, what arrows actually do, what any of this is about.

That's the point.

Category theory strips away all content and keeps only structure. What remains is pure pattern—the shape of relationship abstracted from anything that might be related.

Why Abstraction Matters

Why would you want mathematics without content?

Because content obscures pattern.

When you're studying numbers, you see the patterns that numbers make. When you're studying shapes, you see the patterns that shapes make. But you might not notice that the patterns are the same—that something about how numbers relate to each other is identical to something about how shapes relate to each other.

Category theory creates a level of description where the sameness becomes visible. By stripping away what numbers are made of and what shapes are made of, by keeping only how objects relate and how relations compose, you can see the structural identity that content concealed.

This isn't just mathematical elegance. It has practical power.

When two domains share categorical structure, knowledge transfers. Prove something about the pattern in one domain, and you've proved it for all domains that share the pattern. Discover a technique that works in one domain, and it works everywhere the pattern appears.

Mathematicians discovered this in the 1940s. Category theory began as a tool for studying relations between different mathematical structures—algebra and topology, geometry and logic. It turned out that seemingly unrelated fields had identical categorical structure, and insights could flow between them.

But the mathematics-to-mathematics transfer was just the beginning. The abstraction is so complete that it applies wherever objects and relations exist. Including psychology. Including sociology. Including the domains where meaning lives.

Patterns Across Domains

Consider some examples of categorical structure appearing in different places.

Sets and functions. The category Set has sets as objects and functions as arrows. A function takes each element of one set to some element of another. Functions compose: if f: A → B and g: B → C, you can do f then g to get a function from A to C.

Groups and homomorphisms. The category Grp has groups as objects and group homomorphisms as arrows. A homomorphism preserves the group structure—it maps elements of one group to elements of another while respecting the group operation. Homomorphisms compose.

Topological spaces and continuous functions. The category Top has spaces as objects and continuous functions as arrows. Continuous functions preserve the "nearness" structure of spaces. They compose.

Cognitive states and transitions. We can define a category where objects are cognitive states and arrows are possible transitions—changes from one cognitive state to another through learning, experience, or time. Transitions compose: if you can get from state A to state B, and from B to C, you can get from A to C.

Relational configurations and dynamics. Objects could be configurations of a relationship, arrows could be changes in the relationship. They compose.

These categories have different content. Sets are not groups are not spaces are not minds are not relationships. But the categorical structure—the pattern of how objects relate through arrows that compose—can be the same. And when it's the same, what we learn about the pattern applies everywhere.

Isomorphism: The Precise Meaning of "Same Pattern"

How do we know when patterns are the same? Category theory has a precise answer: isomorphism.

Two objects A and B within a category are isomorphic if there's an arrow f: A → B and an arrow g: B → A such that composing them gives identity: g∘f = id_A and f∘g = id_B. You can transform A into B and back, ending where you started.

Isomorphic objects are interchangeable as far as the category is concerned. Anything you can do with one, you can do with the other. The structure is identical; only the labeling differs.

This concept scales up. Two entire categories can be isomorphic. If you can map all objects and arrows of one category to the other while preserving composition, the categories have the same structure. They're the same pattern, manifested in different mathematical territory.

When categories are isomorphic, proving something in one proves it in the other. The transfer is exact and automatic.

But full isomorphism is strong. It requires perfect matching. Most interesting relationships between categories are weaker—they preserve some structure while losing other structure. Category theory has tools for these partial matches too, but full isomorphism is the gold standard. When you have it, you have identity of pattern in the strongest possible sense.

The Pattern-Centric View

Category theory encourages a fundamental shift in how you think about things.

Stop asking what things are. Start asking how they relate.

In category theory, objects don't have intrinsic natures. They're defined entirely by their relationships—what arrows come in, what arrows go out. An object is its pattern of connection to other objects. Nothing more, nothing less.

This seems strange if you're used to thinking that things have essential properties and relationships are secondary. Category theory inverts this. Relationships are primary. Objects are whatever the relationships need them to be.

Consider: what is the number 2? You might say it's the quantity that comes after 1 and before 3. But that's already a relational definition—2 is what it is because of how it relates to other numbers. What arrows come into 2? Addition from pairs that sum to 2. Multiplication from pairs with product 2. What arrows come out? Successorship to 3. Divisibility into 1. The number 2 is its pattern of arithmetical relations.

The same applies to psychological states. What is "anxiety"? You might try to give an intrinsic definition. But anxiety is also what it connects to—what states can transition into anxiety, what states anxiety can transition into, what triggers it, what resolves it, what it enables and disables. The relational fingerprint is as definitive as any intrinsic property.

Applied to relationships: a person in a relationship is defined by their relational patterns, not by pre-relational essence. Applied to organizations: a role is defined by how it connects to other roles, not by job description in isolation. Applied to cultures: a cultural position is defined by what it relates to, what it opposes, what it enables, what it constrains.

This isn't metaphysical extravagance. It's a methodological shift that makes patterns visible. When you stop trying to find the essence inside things and start mapping the structure of relations between things, you see patterns you couldn't see before.

The Category of Cognitive States

Let's be concrete about how this applies to mind.

Define a category where objects are cognitive states—belief configurations, mental states, ways of being in the world. Each object is a point in the belief manifold we've been discussing throughout this series.

Arrows are transitions. If you can get from state A to state B—through learning, through experience, through time, through effort—that transition is an arrow A → B.

Composition says: if you can get from A to B, and from B to C, there's a path from A to C. Transitions chain.

Identity says: every state can persist in itself. Staying put is a valid arrow.

This is abstract, but it captures something real. Your cognitive life has a categorical structure. There are states you can reach from where you are and states you can't. There are transitions that chain and transitions that don't. The pattern of possible movement is the category.

Different people have different cognitive categories. Different objects available—not everyone can reach every state. Different arrows available—not everyone can make every transition. The category captures what movements are possible for this particular person, which is shaped by their history, their development, their manifold's geometry.

And here's the key: the categorical structure of your cognitive life might be isomorphic—or structurally related—to the categorical structure of your relational life. Or your professional life. Or your creative life. The same pattern of possible and impossible transitions appearing in different domains.

This is why the same problem keeps showing up in different contexts. It's not coincidence. It's not mysticism. It's categorical structure. The pattern is the same; only the instantiation differs.

Why Patterns Recur

This gives us an answer to a question that might have been nagging: why do patterns keep appearing?

Because categorical structure propagates.

When you develop psychologically, you don't develop in isolation. You develop in relationships. The categorical structure of those early relationships—what transitions were possible, what states were reachable—becomes the categorical structure of your internal psychology. The pattern was learned. It's not that you're repeating it; it's that you absorbed it, and now it's part of how your own categories are structured.

Then you enter new relationships. You bring your categorical structure with you. The new relationship's dynamics are shaped by what transitions you can make, what states you can reach—which is shaped by the categories you've already internalized. The pattern recurs because it's built into you.

Because some patterns are more stable than others.

Not all categorical structures are equally robust. Some patterns are fragile—they exist briefly and then dissolve. Others are attractors—they're stable, self-reinforcing, hard to leave once you've entered.

The patterns that keep appearing across domains might be the stable ones. The patterns that survive perturbation, that generalize across contexts, that once established tend to persist. You're not seeing just any patterns; you're seeing the patterns robust enough to propagate widely.

Because abstraction reveals commonality.

When you strip away content and see structure, you see what was shared all along. The patterns were always there; you just couldn't see them through the content.

Learning to see categorically is learning to see through the costumes. The same play, performed by different actors, on different stages, in different languages—the play is recognizable once you know what to look for. The patterns were hiding in plain sight.

Categorical Thinking as Practice

You don't need to prove theorems to think categorically. The technical machinery of category theory is formidable, but the core insight is accessible.

Cultivate pattern-vision. When you encounter something—a relationship, a situation, a problem—ask: what else has this structure? What other domains organize in similar ways? If I stripped away the specific content, what pattern would remain?

Look for structure-preserving maps. When patterns appear to match across domains, ask: what would be preserved if I mapped one to the other? What's the correspondence? Is it exact or approximate? Where does it break down?

Notice when the same relational configuration appears in different costumes. The spiral of your attention. The spiral of your relationship. The spiral of your organization. Same pattern, different material.

This is a learnable literacy. It takes practice, but not special talent. Anyone can learn to see abstractly, to recognize structure through content, to spot the pattern that persists across manifestations.

And it changes what you can see.

When you think categorically, you notice that your family conflict has the same structure as your intrapsychic conflict—and that noticing becomes therapeutic. You notice that the organizational dysfunction at work mirrors the dysfunction in your creative process—and that noticing becomes strategic. You notice that what you're struggling with personally has the same pattern as what the culture is struggling with collectively—and that noticing becomes meaningful.

Pattern connects. Category theory is the mathematics of that connection. Learning to see through its lens reveals a world more structured, more coherent, more unified than it appears to pattern-blind perception.

What Comes Next

If patterns really do propagate across domains—if categorical structure really is preserved across scales—then we need tools to describe how.

How does the pattern at the neural level connect to the pattern at the psychological level? How does the pattern in individuals connect to the pattern in relationships? How does structure survive the jump between scales?

The answer involves a more specific categorical tool: functors. Functors are the maps between categories that preserve structure. They're the conduits through which pattern flows from one domain to another.

If category theory is the mathematics of pattern itself, functors are the mathematics of pattern propagation. And understanding them is essential for understanding how coherence at one scale connects to coherence at another.

The patterns keep appearing. That's not coincidence. That's structure propagating through functors, carrying coherence across the scales.

Comments ()