Climate and Conflict: Drought Wars

Between 2006 and 2010, Syria experienced the worst drought in its recorded history. Rural areas were devastated. Crops failed. Livestock died. Farmers abandoned villages and flooded into cities already strained by Iraqi refugees and unemployment.

In 2011, protests began. Within a year, Syria was in civil war. Half a million people would die. Millions would flee. The Islamic State would emerge from the chaos.

Was climate change responsible for the Syrian war? The question is contested, but it illustrates a larger concern: climate change is reshaping geography itself, and changed geography changes politics.

The Climate-Conflict Hypothesis

Researchers have proposed several pathways from climate change to conflict:

Resource scarcity. As water, arable land, and other resources become scarce, competition intensifies. Groups that previously coexisted fight over diminishing shares. Drought, desertification, and sea-level rise all reduce available resources.

Migration and displacement. Climate change makes some areas uninhabitable. People move. Receiving areas may resist newcomers. Tensions between migrants and hosts can escalate to violence. The climate refugee is becoming a reality.

State weakness. Governments facing climate disasters may fail to respond adequately. Their legitimacy erodes. Authority vacuums create space for armed groups, separatists, or warlords. Climate undermines state capacity.

Economic disruption. Agriculture depends on climate. When harvests fail, rural economies collapse. Unemployment rises. Young men without prospects become recruitable. Economic desperation provides conflict's foot soldiers.

Grievance amplification. Existing ethnic, religious, or political tensions worsen when climate adds resource competition. Groups that might have coexisted when resources were adequate fight when resources are scarce.

None of these is simple or direct. Climate rarely causes conflict alone. But climate can push vulnerable societies from stability into violence.

The Syria example illustrates this complexity. The drought was real and severe. The government response was incompetent and corrupt. Farmers did flood into cities. Protests did begin in drought-affected areas. But Syria also had decades of authoritarian grievances, sectarian tensions, and regional spillover effects. Isolating climate's contribution from other factors is methodologically difficult. What's clear is that climate stress was one of many inputs into a system that became unstable.

The Evidence

The relationship between climate and conflict has been extensively studied:

Cross-national studies find correlations between temperature, rainfall, and conflict incidence. Countries experiencing droughts or heat waves show increased civil conflict risk. The effect is modest but statistically significant.

Historical studies link past climate anomalies to political instability. The Little Ice Age correlates with European wars. El Niño events correlate with civil conflicts globally. Ancient civilizations—Maya, Angkor, Roman—collapsed during climate stress.

Case studies document specific climate-conflict connections. Darfur: desertification pushed herders and farmers into competition. The Sahel: drought fuels insurgency and migration. Lake Chad: shrinking water resources enable Boko Haram recruitment.

The Syria case remains contested. Climate stress was real—the drought was severe, migration was significant, government response was inadequate. But Syria also had authoritarian governance, sectarian tensions, and spillover from Iraq. Climate was one factor among many, perhaps not even the primary one.

The academic consensus: climate is a "threat multiplier." It doesn't cause conflict directly but amplifies existing vulnerabilities. Societies already weak—poor governance, ethnic divisions, economic stress—are pushed toward violence by climate pressure that stronger societies might absorb.

This matters because climate stress is intensifying and will continue to intensify. The populations most affected are often in regions with weakest governance. The combination—increasing climate pressure on increasingly fragile states—suggests more climate-related conflict ahead, even if the causal chains remain complex.

Geography of Climate Vulnerability

Climate change affects different regions differently:

The Sahel. The band across Africa south of the Sahara is one of the world's most climate-vulnerable regions. Rainfall is declining. Desertification is advancing. Population is growing. The combination creates enormous pressure. Conflicts from Mali to Sudan to Nigeria have climate dimensions.

South Asia. Glacial melt threatens the rivers that water over a billion people. The Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra all depend on Himalayan glaciers. As they shrink, water conflict between India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China becomes more likely.

The Middle East. Already water-stressed, the region faces declining aquifers and increasing temperatures. The "fertile crescent" may become unfarmable. Climate contributed to Syria's crisis and may contribute to others.

Island nations and coastal areas. Sea-level rise threatens entire countries—Maldives, Tuvalu, Marshall Islands—and coastal cities worldwide. Where will these populations go? Who will take them?

The Arctic. Warming opens new shipping routes and makes resources accessible. Great powers are competing for Arctic control. Climate change is creating new geographic features worth fighting over.

Central America. The "dry corridor" through Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador is experiencing worsening droughts. Agricultural failure drives migration northward. The connection between climate, failed harvests, and migration to the United States is direct and visible.

The Limits of Climate Determinism

The climate-conflict link is real but complex:

Many climate-stressed societies don't experience conflict. Australia endures severe droughts without civil war. The American Southwest is drying without violence. Strong institutions and governance capacity matter enormously.

Some conflicts occur in climate-stable areas. The Balkans weren't experiencing climate stress during the Yugoslav wars. Rwanda's genocide wasn't climate-driven. Many conflicts have purely political origins.

Causation is difficult to establish. Climate, economics, politics, and conflict interact in complex ways. Attributing specific conflicts to climate requires disentangling many factors.

The time horizons differ. Climate change unfolds over decades; conflicts erupt in months. The connection between slow-moving climate change and specific conflict events is hard to trace.

Adaptation is possible. Humans have adapted to climate variation throughout history. Technology, trade, and governance can mitigate climate impacts. Vulnerability is partly a choice, not purely geographic.

Correlation isn't causation. Many factors correlate with both climate stress and conflict—poverty, weak governance, ethnic tensions. Climate might be a proxy for other vulnerability factors rather than a cause itself.

Climate as Security Threat

Despite complexity, major security establishments treat climate as a threat:

The Pentagon has called climate change a "threat multiplier" since the 2000s. Military planners anticipate increased instability, migration, and resource competition.

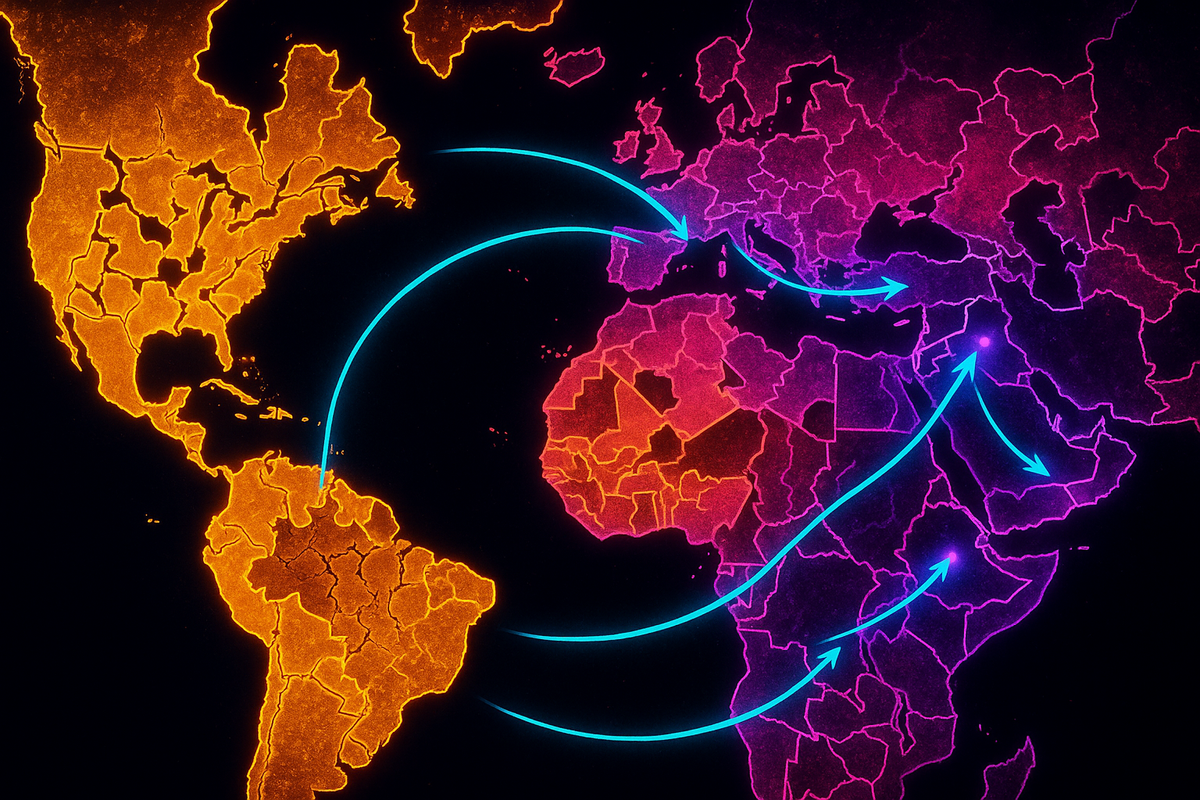

European defense agencies identify climate-driven migration from Africa and the Middle East as a strategic challenge. Border pressure is already evident.

Intelligence assessments flag water stress, food insecurity, and climate migration as conflict drivers for the coming decades. The Arctic's opening creates new strategic competition.

Military installations themselves face climate risks—coastal bases threatened by sea-level rise, facilities vulnerable to extreme weather. The military is a victim of climate change as well as responder to its consequences.

The security framing is controversial. Some argue it militarizes climate response when civilian adaptation is what's needed. Others note that presenting climate as security threat may motivate action that environmental framing hasn't achieved.

What's Coming

Climate change is accelerating. Its security implications will intensify:

Migration will increase. Hundreds of millions of people live in areas that may become uninhabitable by century's end. They will move. Where they go and how they're received will shape politics globally.

State failure will increase. Countries with weak institutions facing severe climate impacts may collapse. Ungoverned spaces enable terrorism, trafficking, and conflict spillover.

Resource competition will intensify. Water, arable land, and habitable space will be contested. Competition can be managed through cooperation—or it can generate conflict.

Geopolitical shifts will occur. Some regions will become less habitable; others more so. Russia and Canada gain from warming; tropical and subtropical regions lose. This reshapes the global balance of power.

Novel conflicts may emerge. Disputes over geoengineering, climate reparations, or resource access may generate new forms of conflict that don't fit current categories.

Cascading failures. Climate impacts can trigger chain reactions—crop failure leads to economic crisis leads to political instability leads to conflict leads to refugee crisis leads to instability elsewhere. Linear thinking underestimates systemic risk.

Policy Implications

If climate drives conflict, responses must address both:

Climate mitigation reduces conflict risk. Preventing severe climate change prevents the instability it would cause. Climate policy is security policy.

Adaptation builds resilience. Societies that adapt successfully to climate change don't experience conflict. Investment in water management, drought-resistant agriculture, and economic diversification reduces vulnerability.

Migration management matters. Climate migration will happen. Whether it causes conflict depends on how it's managed. Planning for migration, creating legal pathways, and supporting receiving communities can reduce violence risk.

Fragile states need support. Countries likely to be pushed into failure by climate stress need governance support now—before crises emerge.

Conflict prevention must incorporate climate. Peace-building that ignores climate is building on sand. Sustainable peace requires sustainable resources.

International cooperation is essential. Climate is a global problem with local effects. Addressing it requires coordination that current institutions struggle to provide. The gap between the scale of climate challenge and the capacity of international institutions is dangerous.

Anticipation matters. By the time climate-driven conflict erupts, it may be too late for prevention. Early warning systems, preemptive adaptation, and proactive migration management require acting before crises materialize.

The Takeaway

Climate change is redrawing geography. Sea levels, rainfall patterns, temperature zones, growing seasons—all are shifting. This isn't just an environmental issue; it's a political geography issue. Changed geography means changed politics.

The climate-conflict link is real but not simple. Climate is a threat multiplier that amplifies existing vulnerabilities rather than creating conflicts from nothing. Where institutions are strong, climate stress can be absorbed. Where institutions are weak, climate becomes one more pressure pushing toward violence.

The coming decades will test this dynamic at unprecedented scale. Climate change's severity, the fragility of affected states, and the global interconnection of consequences will challenge existing frameworks. Understanding the geography of climate vulnerability isn't optional—it's essential for understanding the conflicts to come.

The traditional geopolitics of mountains, rivers, and resources remains relevant—but climate change adds a dynamic element. Geography that shaped history for millennia is now in motion. Coastlines, water tables, growing seasons, habitable zones—all are shifting. Geopolitics must become climatopolitics: understanding not just the terrain as it is, but the terrain as it's becoming.

Further Reading

- CNA Military Advisory Board. (2007). National Security and the Threat of Climate Change. CNA Corporation. - Homer-Dixon, T. (1999). Environment, Scarcity, and Violence. Princeton University Press. - Hsiang, S. M., Burke, M., & Miguel, E. (2013). "Quantifying the Influence of Climate on Human Conflict." Science.

This is Part 7 of the Geography of Power series. Next: "Synthesis: The Terrain Beneath Politics"

Comments ()