The Complex Plane: Numbers as Points in Two Dimensions

The complex plane is the geometric home of complex numbers.

Every complex number z = a + bi corresponds to a point (a, b). Real numbers sit on the horizontal axis. Imaginary numbers sit on the vertical axis. Everything else fills the plane between.

This isn't just a visualization trick. It's a deep insight: complex arithmetic is planar geometry. Addition is vector addition. Multiplication is rotation and scaling.

The algebra and geometry are one.

The Setup

Draw two perpendicular axes:

Horizontal: the real axis. Points like 3, -2, π, √2 live here.

Vertical: the imaginary axis. Points like i, -4i, (√2)i live here.

Every complex number z = a + bi plots at the point (a, b).

Examples:

- 3 + 2i → (3, 2)

- -1 + 4i → (-1, 4)

- 2 - 3i → (2, -3)

- 5 → (5, 0)

- -2i → (0, -2)

Real numbers are on the x-axis (imaginary part zero). Pure imaginaries are on the y-axis (real part zero).

Another Name: The Argand Plane

Named after Jean-Robert Argand, who published this geometric interpretation in 1806.

Also called the Argand diagram, the Gaussian plane (after Gauss), or simply the complex plane.

The idea existed before Argand — Caspar Wessel described it in 1799 — but Argand's name stuck.

Addition as Vector Addition

Complex addition is exactly vector addition.

To add z₁ = a + bi and z₂ = c + di:

z₁ + z₂ = (a + c) + (b + d)i

Geometrically: place z₂'s tail at z₁'s head. The sum is the resulting endpoint.

This is the parallelogram rule: z₁ + z₂ is the diagonal of the parallelogram with sides z₁ and z₂.

The Modulus

The modulus (or absolute value) of z = a + bi is:

|z| = √(a² + b²)

This is the distance from z to the origin — the length of the vector.

Properties:

- |z| ≥ 0, with equality only if z = 0

- |z₁z₂| = |z₁| · |z₂| (moduli multiply)

- |z₁ + z₂| ≤ |z₁| + |z₂| (triangle inequality)

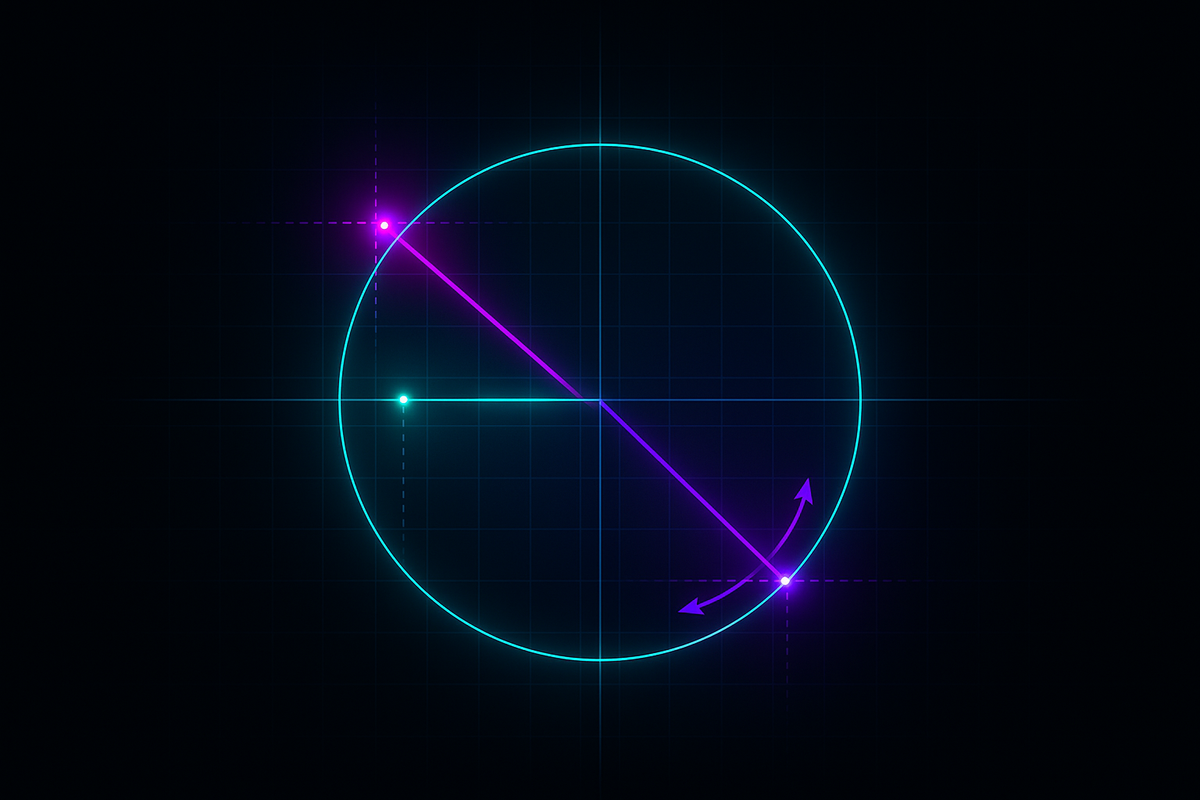

The Argument

The argument (or angle) of z is the angle θ from the positive real axis to z.

arg(z) = θ, where tan θ = b/a.

Convention: θ is measured counterclockwise, typically in radians.

The principal argument restricts θ to (-π, π] or [0, 2π).

For z = a + bi:

- θ = arctan(b/a), adjusted for quadrant.

Examples:

- arg(1) = 0

- arg(i) = π/2

- arg(-1) = π

- arg(-i) = -π/2 (or 3π/2)

Polar Representation

Every complex number can be written in polar form:

z = r(cos θ + i sin θ)

where r = |z| is the modulus and θ = arg(z) is the argument.

This says: z is at distance r from the origin, at angle θ from the positive real axis.

Also written as z = r cis θ (short for "cosine plus i sine").

Multiplication in the Plane

Here's where geometry gets powerful.

Multiply z₁ = r₁(cos θ₁ + i sin θ₁) by z₂ = r₂(cos θ₂ + i sin θ₂):

z₁z₂ = r₁r₂(cos(θ₁ + θ₂) + i sin(θ₁ + θ₂))

Moduli multiply. Arguments add.

Geometrically: to multiply two complex numbers, multiply their lengths and add their angles.

Multiplying by z = r(cos θ + i sin θ):

- Scales by factor r

- Rotates by angle θ

This is why i² = -1: multiplying by i (which has angle π/2) twice gives angle π, pointing at -1.

The Unit Circle

The unit circle is the set of all z with |z| = 1.

In polar form: z = cos θ + i sin θ for any θ.

Every point on the unit circle has modulus 1. Multiplying two unit-circle points gives another unit-circle point (moduli: 1 × 1 = 1, angles add).

The unit circle is a group under multiplication — closed, with identity (1), inverses (z⁻¹ = z̄ when |z| = 1), and associativity.

Conjugate as Reflection

The conjugate of z = a + bi is z̄ = a - bi.

Geometrically: reflect z across the real axis.

If z has angle θ, then z̄ has angle -θ.

Properties using geometry:

- z · z̄ = |z|² (a real number)

- |z̄| = |z|

- z + z̄ = 2a (on the real axis)

Distance in the Plane

The distance between z₁ and z₂ is:

|z₁ - z₂| = √((a₁ - a₂)² + (b₁ - b₂)²)

This is the Euclidean distance formula. Complex subtraction gives a vector from z₂ to z₁; its modulus is the distance.

Circles and Lines

Circle centered at z₀ with radius r: |z - z₀| = r

All points at distance r from z₀.

Disk (filled circle): |z - z₀| < r

Line through z₀ and z₁: z = z₀ + t(z₁ - z₀) for t ∈ ℝ

Perpendicular bisector of segment from z₁ to z₂: |z - z₁| = |z - z₂|

Geometry problems translate directly to complex equations.

Why Geometry Works

Complex multiplication combines scaling and rotation. Real number multiplication only scales (positive: same direction; negative: flip).

By adding the imaginary axis, we get a full 2D space where multiplication becomes geometric transformation.

This is why complex analysis is so powerful. Analytic properties (derivatives, integrals) connect to geometric properties (angles, lengths, mappings).

Conformal Mappings

Complex functions f(z) map the plane to itself.

Conformal maps preserve angles. If two curves meet at angle θ, their images under f also meet at angle θ.

All analytic (complex-differentiable) functions are conformal wherever their derivative is nonzero.

This has applications in:

- Fluid dynamics (streamlines)

- Electrostatics (field lines)

- Cartography (map projections)

The geometry of the complex plane connects to deep mathematics and practical physics.

Summary

The complex plane represents z = a + bi as the point (a, b).

- Modulus |z| = distance from origin

- Argument arg(z) = angle from positive real axis

- Polar form: z = r(cos θ + i sin θ)

- Multiplication: multiply moduli, add arguments

- Conjugate: reflect across real axis

Complex arithmetic is planar geometry. This unification is one of mathematics' great insights.

Further Reading

- Needham, T. Visual Complex Analysis. The definitive geometric approach.

- Brown, J. & Churchill, R. Complex Variables. Standard undergraduate text.

- Ahlfors, L. Complex Analysis. Classic graduate text.

This is Part 3 of the Complex Numbers series. Next: "Polar Form" — complex numbers as magnitude and angle.

Part 3 of the Complex Numbers series.

Previous: The Imaginary Unit i: The Square Root of Negative One Next: Polar Form: Complex Numbers as Rotation and Scaling

Comments ()