Compound Interest: Exponential Growth in Finance

Compound interest is money making money on money.

Simple interest pays you on your original principal. Compound interest pays you on your principal plus previous interest. The difference sounds minor. Over time, it's transformative.

$1,000 at 10% simple interest for 30 years: you earn $100/year, ending with $4,000.

$1,000 at 10% compound interest for 30 years: you end with $17,449.

Same rate, same time. But compound interest earns over four times as much. That's the power of exponential growth applied to money.

The Compound Interest Formula

A = P(1 + r/n)^(nt)

Where:

- A = final amount

- P = principal (initial investment)

- r = annual interest rate (as decimal)

- n = number of compounding periods per year

- t = time in years

Example: $5,000 at 6% compounded monthly for 10 years.

A = 5000(1 + 0.06/12)^(12×10) A = 5000(1.005)^120 A ≈ $9,097

The investment nearly doubles, even at a modest 6%.

Why Compounding Matters

Compare compounding frequencies on $10,000 at 12% for 1 year:

| Compounding | Calculation | Final Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Annual (n=1) | 10000(1.12)¹ | $11,200 |

| Quarterly (n=4) | 10000(1.03)⁴ | $11,255 |

| Monthly (n=12) | 10000(1.01)¹² | $11,268 |

| Daily (n=365) | 10000(1+.12/365)³⁶⁵ | $11,275 |

| Continuous | 10000×e^0.12 | $11,275 |

More frequent compounding earns more, but with diminishing returns. The jump from annual to monthly is bigger than monthly to daily.

The upper limit is continuous compounding: A = Pe^(rt).

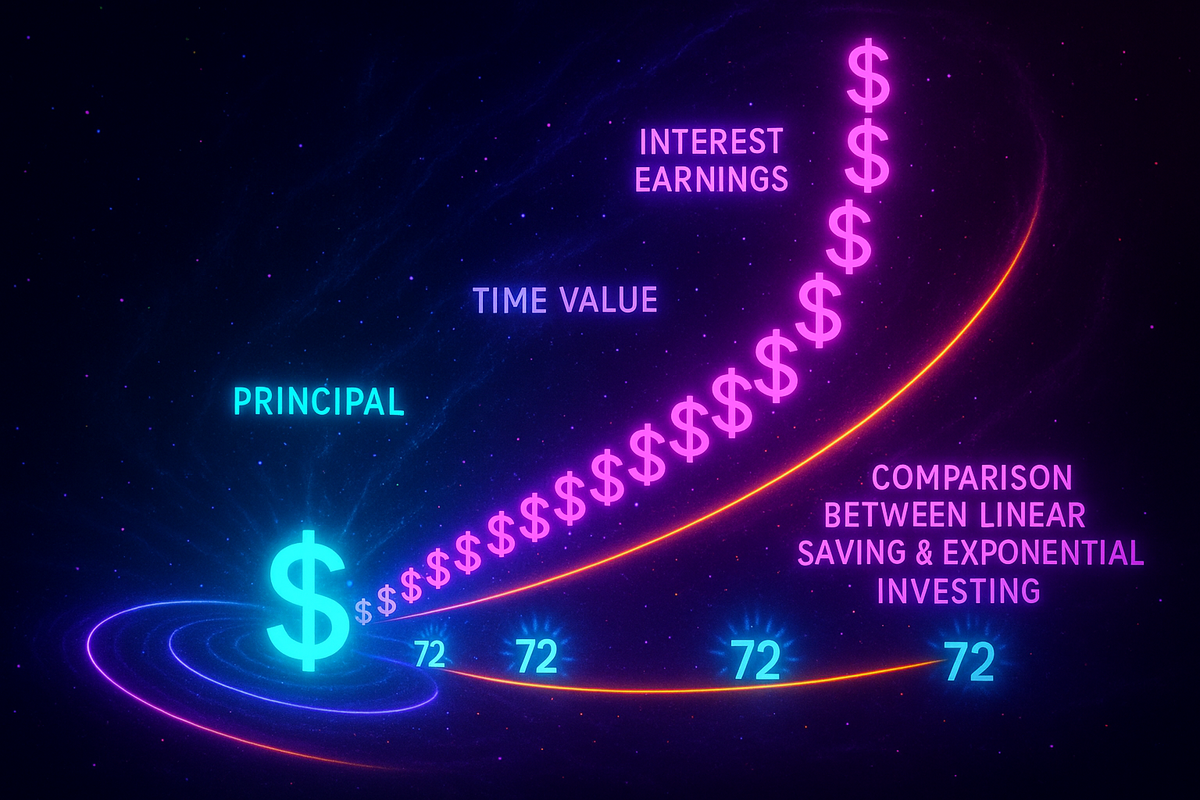

The Rule of 72

Quick mental math for doubling time:

Years to double ≈ 72 / interest rate

At 6%: 72/6 = 12 years to double At 8%: 72/8 = 9 years to double At 12%: 72/12 = 6 years to double

This approximation is surprisingly accurate for rates between 5% and 20%.

Why 72? It's close to 69.3 (= 100 × ln 2) and divisible by many small numbers, making mental math easy.

The Time Value of Money

Compound interest reveals that money has time value. $1 today is worth more than $1 tomorrow because today's dollar can earn interest.

Present value: What is a future sum worth today?

PV = FV / (1 + r)ᵗ

Example: What's $10,000 in 10 years worth today at 5% interest?

PV = 10000 / (1.05)¹⁰ = $6,139

If you can invest at 5%, you only need $6,139 today to have $10,000 in 10 years.

Future value: What will today's money be worth later?

FV = PV × (1 + r)ᵗ

This is just the compound interest formula restated.

The Power of Starting Early

The earlier you invest, the more time compounding has to work.

Consider three investors who each invest $200/month until age 65:

Alice starts at 25 (40 years of investing): Total invested: $96,000 At 7% return: ~$480,000

Bob starts at 35 (30 years of investing): Total invested: $72,000 At 7% return: ~$227,000

Carol starts at 45 (20 years of investing): Total invested: $48,000 At 7% return: ~$98,000

Alice invested only $24,000 more than Bob but ends with more than double. Carol invested half as much as Alice but ends with less than a quarter.

The extra years matter more than the extra dollars. Time is the secret ingredient.

The Danger of Compound Interest on Debt

Compound interest works against you on debt.

Credit card at 24% APR (2% monthly), starting balance $5,000, minimum payments:

- If minimum payment is 2% of balance: you pay forever (interest roughly equals payment)

- If minimum payment is 3% of balance: takes 20+ years to pay off

- Total interest paid can exceed the original debt several times over

The same math that builds wealth destroys debt capacity. Compound interest is neutral—it amplifies whatever direction you're going.

Continuous Compounding

As compounding becomes infinitely frequent:

A = Pe^(rt)

This is the limit of (1 + r/n)^(nt) as n → ∞.

Example: $10,000 at 5% continuous for 20 years:

A = 10000 × e^(0.05 × 20) = 10000 × e^1 ≈ $27,183

Continuous compounding is a mathematical idealization, but it's used in:

- Options pricing (Black-Scholes model)

- Theoretical finance

- Any situation where you want clean calculus

For practical banking, daily or monthly compounding is close enough.

Real vs. Nominal Returns

Inflation erodes purchasing power. A 10% return with 3% inflation gives only 7% real return.

Real return ≈ Nominal return - Inflation rate

More precisely: (1 + real) = (1 + nominal)/(1 + inflation)

$100 invested at 10% nominal for 30 years gives $1,745 in nominal dollars.

With 3% inflation, those dollars buy what $569 bought at the start. Still good—but not as spectacular as the nominal number suggests.

Always think about real returns when making long-term plans.

Annuities and Regular Investments

What if you invest a fixed amount regularly?

Future value of annuity: FV = PMT × [(1+r)ⁿ - 1]/r

Example: Invest $500/month at 8% annual (0.67% monthly) for 20 years:

FV = 500 × [(1.0067)^240 - 1]/0.0067 ≈ $295,000

You invested $120,000 total. Compound interest contributed $175,000.

This is how retirement accounts work. Regular contributions plus compound interest builds substantial wealth.

Effective Annual Rate

When interest is compounded more than annually, the effective annual rate (EAR) exceeds the stated rate.

EAR = (1 + r/n)ⁿ - 1

Example: 12% APR compounded monthly:

EAR = (1 + 0.12/12)^12 - 1 = (1.01)^12 - 1 ≈ 12.68%

The effective rate is what you actually earn. Always compare investments by EAR, not APR.

For continuous compounding: EAR = e^r - 1

The Lesson

Compound interest is exponential growth applied to money. The formulas are just 2ˣ dressed in financial notation.

Key insights:

- Time matters more than rate. Doubling your investment period can more than double your returns.

- Start early. The first dollars you invest work the longest.

- Compounding frequency matters—but diminishes. Monthly to daily makes little difference.

- It cuts both ways. Compound interest builds wealth and deepens debt with equal efficiency.

- Think in real terms. Subtract inflation to understand actual purchasing power.

Einstein may never have said "compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world," but the sentiment is right. It's the patient, unstoppable growth that rewards those who understand time.

Part 5 of the Exponential Functions series.

Previous: The Number e: The Base That Calculus Prefers Next: The Exponential Function eˣ: The Most Important Function in Mathematics

Comments ()