Convergence Tests: When Does an Infinite Series Have a Sum?

You don't need to find the sum to know it exists.

Most infinite series can't be summed exactly. We don't have a nice formula like 1/(1-r). But we can still determine whether the sum is finite or infinite.

That's what convergence tests do. They answer the binary question—converges or diverges—without computing the actual sum.

This is like a smoke detector versus a fire investigation. The test tells you something's there (or not). Finding what's there is a different problem.

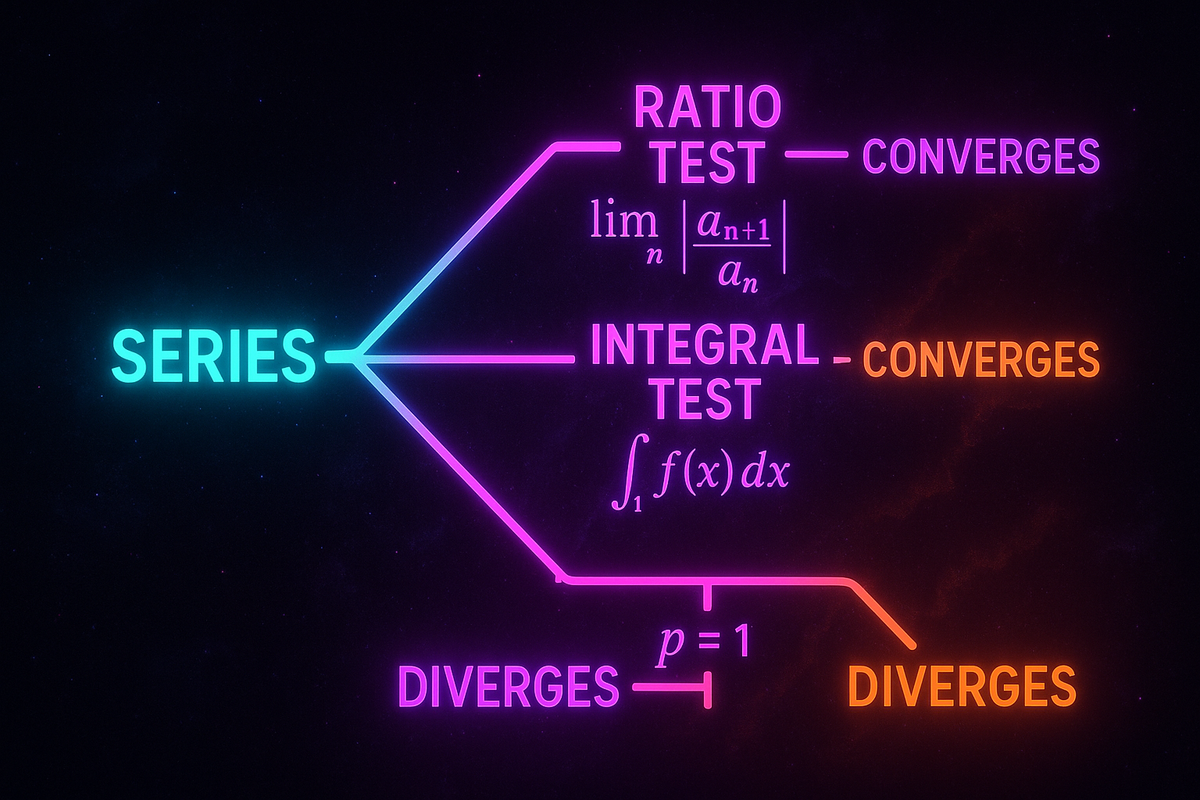

The Decision Tree

When facing a series ∑aₙ, work through these tests in order:

- Divergence Test (nth term test): Does aₙ → 0? If not, diverges.

- Recognize special types: Is it geometric? p-series? Alternating?

- Comparison tests: Can you compare to a known series?

- Ratio/Root tests: Do terms have factorials or exponentials?

- Integral test: Can you integrate the function f(n) = aₙ?

No single test works for all series. But these five handle most cases.

Test 1: The Divergence Test

If lim(n→∞) aₙ ≠ 0, the series diverges.

This is the first check. If terms don't shrink to zero, the series blows up.

Example: ∑n/(n+1). Here aₙ = n/(n+1) → 1 ≠ 0. Series diverges.

Example: ∑sin(n). The terms oscillate, never approaching 0. Series diverges.

Warning: The converse fails. aₙ → 0 doesn't guarantee convergence. The harmonic series has 1/n → 0 but still diverges.

The divergence test is a quick filter. Passing it means the series might converge. Failing it means certain divergence.

Test 2: Geometric and p-Series Recognition

Geometric series ∑arⁿ:

- Converges if |r| < 1, to a/(1-r)

- Diverges if |r| ≥ 1

p-series ∑1/nᵖ:

- Converges if p > 1

- Diverges if p ≤ 1

Memorize these. Many series can be quickly identified as geometric or p-series.

Example: ∑(3/4)ⁿ is geometric with r = 3/4 < 1. Converges.

Example: ∑1/n^1.5 is p-series with p = 1.5 > 1. Converges.

Example: ∑1/√n = ∑1/n^0.5 is p-series with p = 0.5 < 1. Diverges.

Test 3: The Comparison Test

If 0 ≤ aₙ ≤ bₙ for all n:

- If ∑bₙ converges, so does ∑aₙ (smaller than convergent = convergent)

- If ∑aₙ diverges, so does ∑bₙ (larger than divergent = divergent)

The idea: bound your mystery series by a known series.

Example: Does ∑1/(n² + 1) converge?

Compare to ∑1/n² (which converges, p = 2).

Since 1/(n² + 1) < 1/n² for all n, and ∑1/n² converges, so does ∑1/(n² + 1).

Example: Does ∑1/(n + 5) converge?

Compare to ∑1/n (which diverges, harmonic).

For large n, 1/(n+5) ≈ 1/n. More precisely, 1/(n+5) > 1/2n for n ≥ 5.

Since ∑1/2n = (1/2)∑1/n diverges, so does ∑1/(n+5).

Test 4: The Limit Comparison Test

If lim(n→∞) aₙ/bₙ = L, where 0 < L < ∞:

- ∑aₙ and ∑bₙ both converge or both diverge.

This is more flexible than direct comparison. You don't need inequalities, just a finite nonzero limit.

Example: Does ∑n/(n³ + 5) converge?

Compare to ∑1/n² (known to converge).

lim[n/(n³+5)] / [1/n²] = lim n³/(n³+5) = 1.

Since the limit is 1 (nonzero and finite), both series converge or both diverge. ∑1/n² converges, so ∑n/(n³+5) converges.

The trick: for rational functions, compare to the dominant term behavior.

Test 5: The Ratio Test

Compute L = lim |aₙ₊₁/aₙ|:

- L < 1: converges absolutely

- L > 1: diverges

- L = 1: inconclusive

Use this for factorials and exponentials.

Example: ∑n!/10ⁿ

aₙ₊₁/aₙ = [(n+1)!/10ⁿ⁺¹] / [n!/10ⁿ] = (n+1)/10

As n → ∞, this ratio → ∞. L = ∞ > 1. Series diverges.

Example: ∑2ⁿ/n!

aₙ₊₁/aₙ = [2ⁿ⁺¹/(n+1)!] / [2ⁿ/n!] = 2/(n+1) → 0

L = 0 < 1. Series converges.

The ratio test compares the series to a geometric series. If the ratio is eventually less than some r < 1, the series converges faster than that geometric series.

Test 6: The Root Test

Compute L = lim |aₙ|^(1/n):

- L < 1: converges absolutely

- L > 1: diverges

- L = 1: inconclusive

Similar to ratio test, but sometimes easier when aₙ is already an nth power.

Example: ∑(n/(2n+1))ⁿ

|aₙ|^(1/n) = n/(2n+1) → 1/2 < 1. Converges.

Example: ∑nⁿ/3ⁿ = ∑(n/3)ⁿ

|aₙ|^(1/n) = n/3 → ∞ > 1. Diverges.

Test 7: The Integral Test

If f(x) is positive, continuous, and decreasing for x ≥ 1, and f(n) = aₙ:

∑aₙ and ∫₁^∞ f(x)dx converge or diverge together.

This connects series to integrals.

Example: Does ∑1/n(ln n)² converge? (For n ≥ 2)

Let f(x) = 1/(x(ln x)²). This is positive, continuous, decreasing for x ≥ 2.

∫₂^∞ 1/(x(ln x)²) dx. Let u = ln x, du = dx/x.

= ∫{ln 2}^∞ 1/u² du = [-1/u]{ln 2}^∞ = 0 + 1/ln 2 < ∞.

The integral converges, so the series converges.

Example: Does ∑1/(n ln n) converge? (For n ≥ 2)

∫₂^∞ 1/(x ln x) dx. Let u = ln x.

= ∫{ln 2}^∞ 1/u du = [ln u]{ln 2}^∞ = ∞.

The integral diverges, so the series diverges.

Test 8: The Alternating Series Test

For ∑(-1)ⁿaₙ with aₙ > 0:

If aₙ is decreasing and aₙ → 0, the series converges.

Bonus: the error after n terms is less than aₙ₊₁.

Example: ∑(-1)ⁿ/n

Terms 1/n decrease to 0. Series converges (to ln 2).

Example: ∑(-1)ⁿn/(n+1)

Terms n/(n+1) → 1 ≠ 0. Fails the aₙ → 0 condition. By divergence test, diverges.

When Tests Fail

Sometimes L = 1 in ratio/root tests, or no comparison works.

Options:

- Try a different test

- Use more advanced tests (Raabe's test, Kummer's test)

- Accept that some series are genuinely hard

The series ∑1/(n(ln n)(ln ln n)) requires careful analysis. It diverges, but slowly—you need refined tools to prove it.

Quick Reference Table

| Series Type | Test to Use | Converges if |

|---|---|---|

| Terms don't → 0 | Divergence | Never (diverges) |

| Geometric ∑arⁿ | Recognition | |

| p-series ∑1/nᵖ | Recognition | p > 1 |

| Rational functions | Limit comparison | Compare to dominant term |

| Factorials, exponentials | Ratio test | L < 1 |

| nth powers | Root test | L < 1 |

| f(n) integrable | Integral test | ∫f(x)dx converges |

| Alternating | Alternating series test | aₙ decreasing to 0 |

Why Tests Matter

- They bypass computation. You don't need the sum to know it exists.

- They classify behavior. Convergent series behave fundamentally differently than divergent ones.

- They guide approximation. Knowing a series converges tells you partial sums are meaningful approximations.

- They're practical. Most series in applications can't be summed exactly. Convergence tests are what we actually use.

The tests are tools, not theory. They answer the fundamental question: is this infinite sum finite?

Part 9 of the Sequences Series series.

Previous: Infinite Series: When Sums Never Stop but Still Converge Next: Power Series: Polynomials That Go On Forever

Comments ()