Coordinate Geometry: Where Algebra Meets Geometry

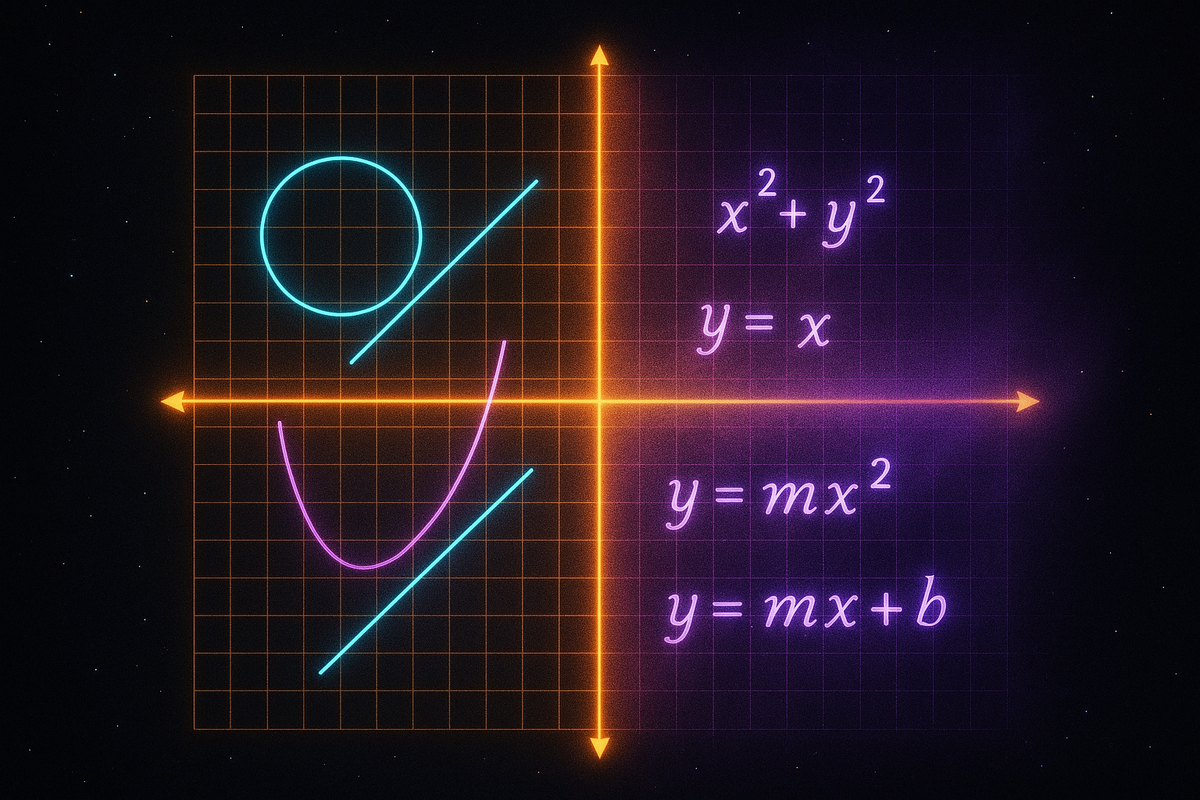

Every shape is an equation. Every equation is a shape.

Draw a circle. That circle is also the equation x² + y² = r². Draw a line. That line is also y = mx + b. The shape and the equation are the same object, viewed differently.

Here's the unlock: coordinates translate between pictures and formulas. Anything you can draw, you can write as an equation. Anything you can write as an equation, you can draw. Geometry and algebra aren't separate subjects — they're two languages for the same ideas.

This is why Descartes' 1637 invention of coordinate geometry was revolutionary. Suddenly you could solve geometry problems with algebra, and visualize algebra problems with geometry. Two toolboxes became one.

The Coordinate Plane

Take two perpendicular number lines. The horizontal one is the x-axis. The vertical one is the y-axis. They cross at the origin, labeled (0, 0).

Every point in the plane now has an address: (x, y).

- x tells you how far right (positive) or left (negative) of the origin

- y tells you how far up (positive) or down (negative) from the origin

The point (3, 2) is 3 units right, 2 units up. The point (-1, 4) is 1 unit left, 4 units up. The point (0, -5) is on the y-axis, 5 units down.

The Four Quadrants

The axes divide the plane into four regions:

Quadrant I (upper right): x > 0, y > 0 — both positive Quadrant II (upper left): x < 0, y > 0 — x negative, y positive Quadrant III (lower left): x < 0, y < 0 — both negative Quadrant IV (lower right): x > 0, y < 0 — x positive, y negative

Points on the axes aren't in any quadrant.

Distance Formula

How far apart are two points (x₁, y₁) and (x₂, y₂)?

This is the Pythagorean theorem applied:

d = √[(x₂ - x₁)² + (y₂ - y₁)²]

Horizontal distance: |x₂ - x₁|. Vertical distance: |y₂ - y₁|. These are legs of a right triangle. The hypotenuse is the actual distance.

Every distance calculation in coordinate geometry is Pythagoras in disguise.

Midpoint Formula

The point exactly halfway between (x₁, y₁) and (x₂, y₂) is:

((x₁ + x₂)/2, (y₁ + y₂)/2)

Just average the x-coordinates and average the y-coordinates.

Halfway between (1, 3) and (5, 7)? Average x: (1+5)/2 = 3. Average y: (3+7)/2 = 5. Midpoint: (3, 5).

Lines: The Simplest Shapes

A line is the simplest relationship between x and y: a constant rate of change.

Slope-intercept form: y = mx + b

- m is the slope: how much y increases when x increases by 1

- b is the y-intercept: where the line crosses the y-axis

A line with slope 2 and y-intercept 3 is y = 2x + 3. For every step right, you go 2 steps up. When x = 0, y = 3.

Slope

Slope measures steepness:

m = (y₂ - y₁)/(x₂ - x₁) = rise/run

- Positive slope: line goes up to the right

- Negative slope: line goes down to the right

- Zero slope: horizontal line

- Undefined slope: vertical line (can't divide by zero)

Slope is the rate of change. In physics, it's velocity. In economics, it's marginal rate. The concept applies far beyond geometry.

Parallel and Perpendicular

Two lines are parallel if they have the same slope. They never meet — they're going the same direction.

Two lines are perpendicular if their slopes are negative reciprocals: m₁ × m₂ = -1.

If one line has slope 2, a perpendicular line has slope -1/2. If one has slope -3/4, a perpendicular line has slope 4/3.

Perpendicular means "as different as possible" — slopes that multiply to -1 represent directions at 90°.

Circles

A circle centered at (h, k) with radius r is:

(x - h)² + (y - k)² = r²

This is the distance formula: all points (x, y) whose distance from (h, k) equals r.

Circle centered at origin: x² + y² = r²

Circle centered at (2, -3) with radius 5: (x - 2)² + (y + 3)² = 25

Parabolas

A parabola is the graph of a quadratic equation:

y = ax² + bx + c

- a > 0: opens upward (smiling)

- a < 0: opens downward (frowning)

- |a| large: narrow parabola

- |a| small: wide parabola

The vertex is the highest or lowest point. For y = ax² + bx + c, the x-coordinate of the vertex is -b/(2a).

Parabolas appear in physics — the path of a thrown ball is a parabola.

Transformations in Coordinates

Coordinate geometry makes transformations calculable:

Translation (shift): Add constants to x and y.

- (x, y) → (x + a, y + b) shifts right by a, up by b

Reflection over x-axis: (x, y) → (x, -y)

Reflection over y-axis: (x, y) → (-x, y)

Reflection over origin: (x, y) → (-x, -y)

Rotation 90° counterclockwise about origin: (x, y) → (-y, x)

Scaling by factor k from origin: (x, y) → (kx, ky)

These become matrix operations in linear algebra — a more powerful framework.

Intersections

Where do two curves meet? Set their equations equal and solve.

Line meets line: Solve the system of two linear equations. Either one solution (they cross), no solution (parallel), or infinite solutions (same line).

Line meets circle: Substitute the line equation into the circle equation. Get a quadratic. Two solutions (line crosses circle), one solution (tangent), or no real solutions (line misses).

Circle meets circle: Subtract one equation from the other to get a linear equation. That's the line containing their intersection points. Then solve line-meets-circle.

Conic Sections Preview

Circles are one of four conic sections — curves you get by slicing a cone:

- Circle: slice perpendicular to the axis

- Ellipse: slice at an angle (but not steep enough to hit the base)

- Parabola: slice parallel to the edge of the cone

- Hyperbola: slice steep enough to cut both halves of a double cone

Each has a coordinate equation:

- Circle: (x-h)² + (y-k)² = r²

- Ellipse: (x-h)²/a² + (y-k)²/b² = 1

- Hyperbola: (x-h)²/a² - (y-k)²/b² = 1

- Parabola: y - k = a(x-h)² (or similar)

The equations look similar because the shapes are related — all slices of the same cone.

Why This Matters

Coordinate geometry is the bridge between intuition and calculation.

See a geometric problem? Convert it to equations, solve algebraically, interpret the answer geometrically.

Have an equation? Graph it to understand its behavior visually.

GPS works because locations are coordinates and distances are calculated with the distance formula. Computer graphics work because shapes are equations that can be transformed mathematically. Machine learning works because "similar" means "close together" in a coordinate space.

The Core Insight

Shapes are equations. Equations are shapes.

Coordinates let you translate between the visual (geometry) and the symbolic (algebra). This translation is the foundation of all computational geometry.

When Descartes merged these two ways of thinking, mathematics took a leap. Problems unsolvable in one domain became routine in the other.

The x-y plane isn't just a convenience. It's a unification — proof that geometry and algebra were always the same subject, seen from different angles.

Part 9 of the Geometry series.

Previous: Volume and Surface Area: Three-Dimensional Measurement Next: Synthesis: Geometry as the Mathematics of Space

Comments ()