Cultural Attractors: Why Certain Ideas Keep Emerging

Cultural Attractors: Why Certain Ideas Keep Emerging

Series: Gene-Culture Coevolution | Part: 4 of 9

Why do agricultural societies around the world independently develop moralizing gods? Why do healing traditions from Tibet to Brazil converge on trance states and plant medicines? Why do hierarchical societies repeatedly invent similar status markers, kinship systems, and power structures?

Cultural evolution isn't random drift. Certain configurations keep appearing—not because of contact or diffusion, but because they're attractors in cultural possibility space. Just as physical systems settle into stable configurations, cultural systems are drawn toward patterns that fit human cognition, social dynamics, and environmental constraints.

This is the concept of cultural attractors: stable equilibria in the space of possible cultures that human societies repeatedly discover and converge upon.

What Makes an Attractor

In dynamical systems, an attractor is a state (or set of states) that a system tends toward over time, regardless of starting conditions. Drop a ball anywhere in a bowl, and it rolls to the bottom. The bottom is an attractor.

Cultural attractors work similarly. They're configurations of beliefs, practices, and social structures that are stable under cultural transmission—resistant to drift, mutation, and environmental perturbation.

What makes a cultural pattern an attractor?

Cognitive fit: Ideas that align with human cognitive architecture stick better. Our brains evolved to detect agency, track social relationships, and learn causal patterns. Cultural variants that match these cognitive templates get remembered, transmitted, and elaborated more reliably than those that don't.

Social functionality: Practices that help groups coordinate, cooperate, or compete persist because they work. A conflict resolution mechanism that actually reduces violence gets kept. A ritual that successfully synchronizes group members becomes traditional.

Transmission advantage: Some cultural variants are just easier to learn and teach. Simple narratives outcompete complex ones. Memorable symbols spread faster than abstract concepts. The transmission process itself filters for certain properties.

Coordination equilibria: Many cultural practices stick because everyone doing the same thing creates value. Driving on the same side of the road only works if everyone does it. Once a convention establishes, it's costly to deviate—even if an alternative would be equally good.

The result: cultural possibility space has structure. Not all cultural configurations are equally stable. Some are local maxima that societies easily get stuck in. Some are unstable and collapse. And some are deep attractors that cultures around the world independently discover.

Examples of Cultural Attractors

Moralizing High Gods

Small-scale societies often have supernatural beings—spirits, ancestors, tricksters. But they're rarely concerned with human morality. You don't anger the forest spirit by lying; you anger it by violating its territory.

Large-scale societies, by contrast, overwhelmingly develop moralizing gods—deities who care about human behavior, punish norm violations, and enforce cooperation.

This pattern has emerged independently in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Mesoamerica, China, India, and the Mediterranean. It's not diffusion. It's convergent cultural evolution.

Why? Ara Norenzayan's research suggests moralizing gods solve a coordination problem. Small groups can enforce norms through reputation and direct punishment. But at scale, you interact with strangers who don't know your reputation. Belief in supernatural punishment creates an internalized enforcement mechanism that doesn't require face-to-face monitoring.

Groups with moralizing gods can coordinate at larger scales. They outcompete groups without such beliefs. The cultural variant spreads not because it's true but because it's functional. The attractor is deep: societies under selection pressure for large-scale cooperation repeatedly invent supernatural moral enforcement.

Shamanic Healing

Trance states, spirit journeys, altered consciousness, plant medicines—these appear in healing traditions worldwide. Siberian shamanism, Amazonian ayahuasca ceremonies, African sangoma practices, and North American vision quests show striking similarities despite geographic isolation.

Why? Several factors create the attractor:

Altered states are universal: The neurobiology of trance is species-wide. Drumming, dancing, fasting, and psychoactive plants all reliably produce predictable phenomenology—ego dissolution, boundary dissolution, entity encounters, visionary experiences.

Healing as meaning-making: Much illness is coherence collapse—loss of narrative integration, social disconnection, physiological dysregulation. Shamanic practice provides a meaning framework that can restore coherence. The ritual context, symbolic interpretation, and social reintegration all serve genuine therapeutic functions.

Transmission advantage: Dramatic altered-state experiences are memorable. They create committed practitioners. The phenomenology itself reinforces the tradition.

The attractor isn't the specific details—each culture elaborates its own mythology, pharmacology, and ritual structure. But the core pattern—using altered states for healing within a cosmological framework—keeps appearing because it fits human neurobiology and social needs.

Status Hierarchies

Egalitarian societies exist. But they're rare, require active mechanisms to prevent hierarchy, and tend to collapse under population pressure.

The default attractor is hierarchy. Not because humans are naturally tyrannical, but because coordination problems in groups above ~150 people are solved more easily with leadership structures than with pure consensus.

The specific form varies—hereditary chiefs, elected leaders, gerontocracies, military commanders, religious authorities. But the pattern of differentiated status with asymmetric decision-making power appears again and again.

Why? Game theory and organizational dynamics. As group size increases, coordination costs rise exponentially if everyone negotiates with everyone else. Hierarchical structures reduce coordination costs by consolidating decision-making. The structure is stable because it's functional.

Egalitarianism requires constant work to maintain—leveling mechanisms, ridicule of status-seekers, redistribution practices. Hierarchy is the low-energy configuration that societies fall into without active resistance.

How Attractors Shape Cultural Evolution

Cultural attractors don't determine culture. They constrain it—shaping the distribution of possible cultures while leaving enormous room for variation.

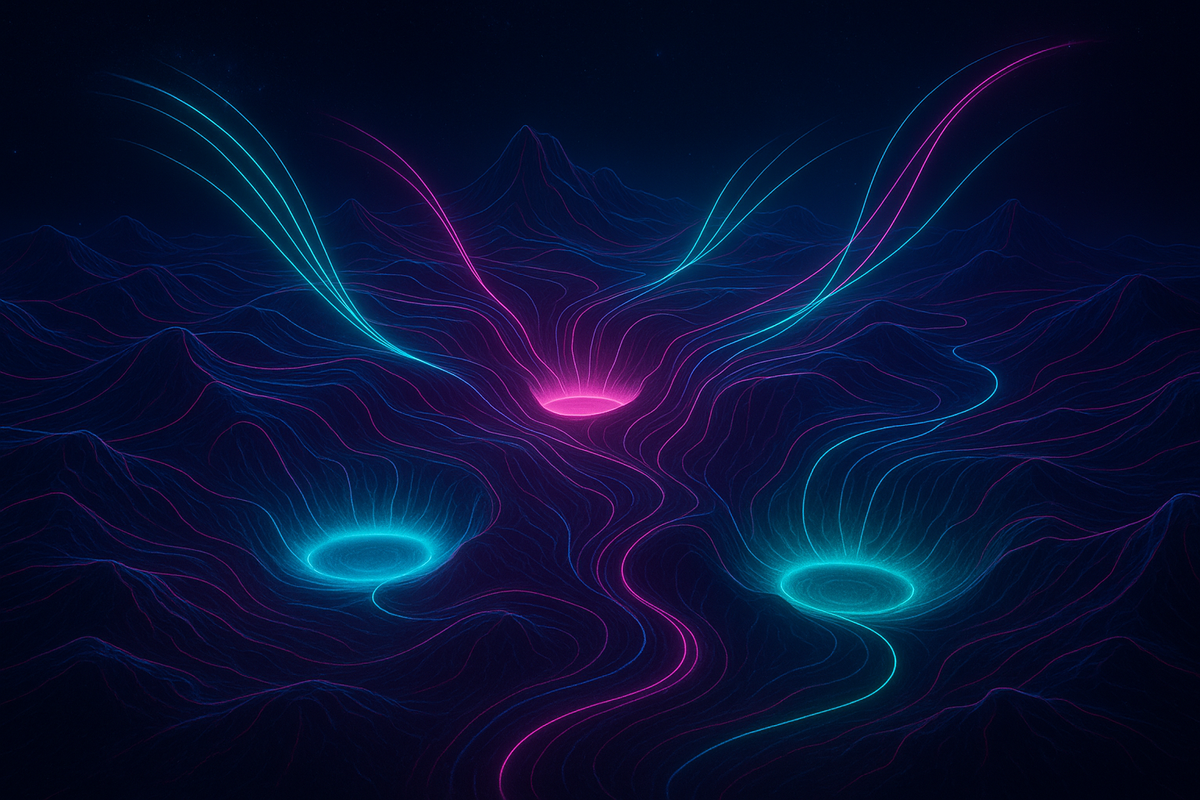

Think of it as landscape navigation. Cultures move through possibility space, shaped by random drift, environmental pressures, and historical contingency. But the landscape has features—peaks, valleys, ridges, basins. Some regions are easy to reach from many starting points. Some are hard to access but stable once attained. Some are unstable and collapse quickly.

Cultural evolution is the process of moving through this structured landscape. Attractors are the stable basins cultures settle into.

Attractors and Historical Contingency

Attractors don't erase history. They interact with it.

Path dependence is real: the route you took affects where you end up. QWERTY keyboards are a stable attractor not because they're optimal but because switching costs create lock-in. Driving on the left vs. right is arbitrary, but once established, it's costly to change.

Multiple attractors can exist: Different stable configurations are possible depending on starting conditions and environmental context. Pastoralist and agricultural societies face different selection pressures and converge on different social structures—both stable, both functional, both attractors.

Attractor switching happens: Cultural systems can jump from one basin to another when perturbations are large enough. Modernization is often this kind of transition—a shift from one stable configuration (traditional society) to another (industrial society), with a turbulent transition period between attractors.

The Cognitive Foundations

Dan Sperber's work on cultural epidemiology provides the cognitive grounding. Ideas don't transmit like genes—perfect copying from mind to mind. They reconstruct in each mind based on inputs plus cognitive priors.

This reconstruction process creates inferential drift toward cognitive attractors. If I tell you a story and you retell it, you don't replay my exact words. You reconstruct the story based on what you remember plus your expectations about how stories work. The result drifts toward story templates your brain finds natural.

Cognitive attractors are patterns that brains easily generate, remember, and reproduce. They include:

- Agent-based explanations: We preferentially attribute causation to intentional agents rather than impersonal forces

- Teleological thinking: We see purpose and design where there is none

- Binary categories: We carve continuous variation into discrete kinds

- Moral framing: We interpret events through frameworks of right and wrong

Cultural variants that fit these cognitive grooves stick. Variants that don't, mutate toward variants that do.

This is why minimally counterintuitive concepts (Pascal Boyer's insight) are so sticky. A tree that watches you is memorable because it violates expectations in one dimension (trees don't watch) while conforming in others (trees are physical objects). The slight violation creates salience; the conformity makes it cognitively digestible.

Supernatural beings across cultures tend to be minimally counterintuitive: invisible but still located, immortal but still persons, all-knowing but still responsive. These are attractors in the space of god-concepts.

Attractors as Coherence Basins

In AToM terms, cultural attractors are coherence basins—regions of cultural state-space where systems maintain stable integration over time.

Cultures that land in attractor basins can persist. They're self-reinforcing: the practices fit the cognition, the cognition supports the practices, the social structures emerge from both, and everything locks together in mutual stabilization.

Cultures far from attractors are unstable. They require constant energy to maintain. Unless there's strong selection pressure or intentional effort, they drift toward nearby attractors.

This is why cultural revolutions often fail to create lasting change. You can force a society out of one attractor through coercion or crisis. But unless you can stabilize it in a new attractor, it snaps back to familiar configurations once the forcing stops.

The deep attractors—moralizing gods, status hierarchies, kinship structures, healing practices—aren't arbitrary social constructions. They're stable configurations of the human possibility space, shaped by biology, cognition, and social dynamics. Cultures can resist them, modify them, or navigate around them. But they can't ignore them.

We're not determined by attractors. But we're constrained by them—and understanding the landscape helps explain why human cultures, despite their diversity, show the patterns they do.

This is Part 4 of the Gene-Culture Coevolution series, exploring how genes and culture evolve together to make humans uniquely human.

Previous: Why Humans Are Cultural Apes: The Cognitive Equipment for Culture

Next: Why Humans Form Religious Groups: Cognitive and Social Foundations

Further Reading

- Sperber, D. (1996). Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Blackwell.

- Boyer, P. (2001). Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. Basic Books.

- Norenzayan, A. (2013). Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict. Princeton University Press.

- Henrich, J. (2016). The Secret of Our Success. Princeton University Press.

Comments ()