Curl: How Much Does a Field Rotate?

Curl measures rotation in a vector field. It tells you how much and around which axis the field swirls at each point. Unlike divergence (which produces a scalar), curl produces a vector: the axis of rotation, with magnitude equal to the strength of rotation.

The formula in Cartesian coordinates looks like a cross product. For F = (P, Q, R):

∇ × F = (∂R/∂y - ∂Q/∂z, ∂P/∂z - ∂R/∂x, ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y)

But again, the formula is less important than the geometric intuition: curl measures circulation density. If you put a tiny paddle wheel at a point and the field makes it spin, the curl is nonzero. The direction of the curl vector is the axis of rotation (via the right-hand rule). The magnitude is the angular speed.

The Geometric Picture

Imagine a tiny loop around a point in the field. Calculate the circulation (line integral) around that loop. Divide by the area enclosed. Take the limit as the loop shrinks to the point.

That's curl in the direction perpendicular to the loop. The curl vector points along the axis that maximizes this circulation density.

If the field rotates around the point, curl is nonzero. If the field is irrotational (no swirl), curl is zero everywhere.

Examples:

- Rotating flow: F = (-y, x, 0). This field circulates counterclockwise around the z-axis. The curl is (0, 0, 2), pointing up along the z-axis.

- Radial field: F = (x, y, z). This field spreads outward with no rotation. The curl is (0, 0, 0)—zero everywhere.

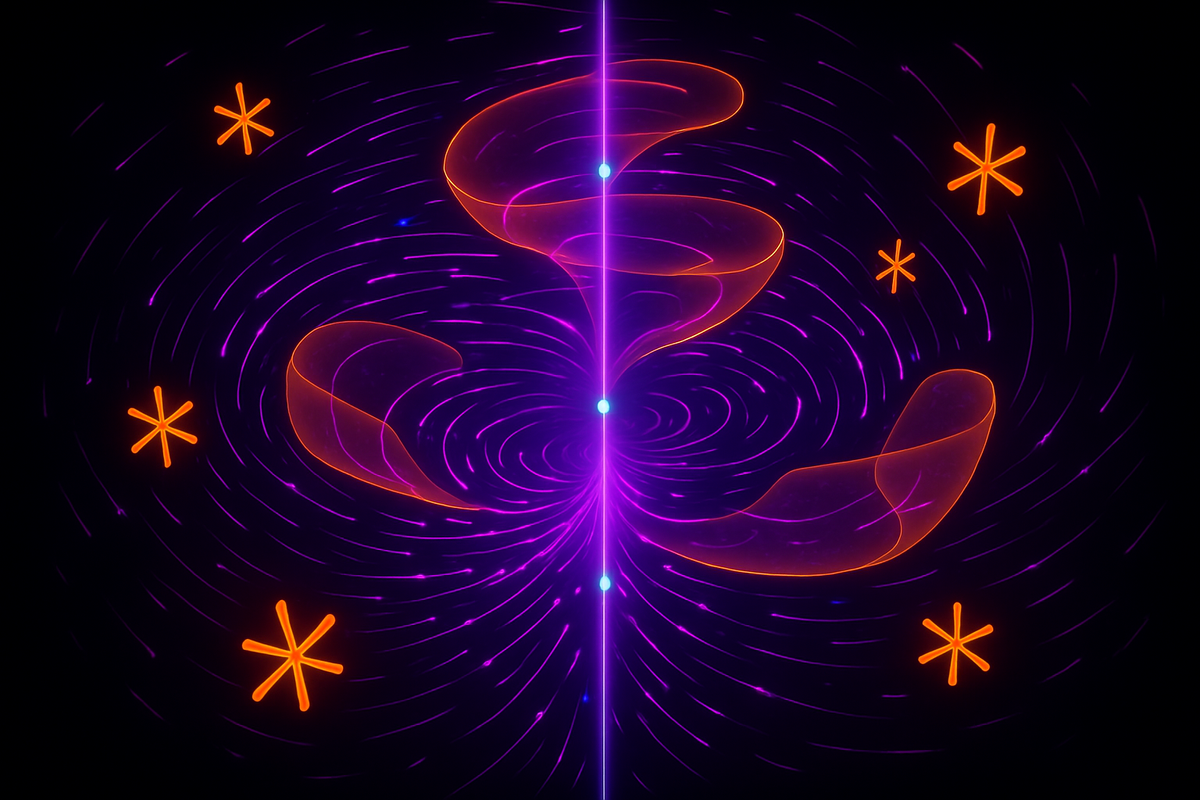

- Magnetic field around a wire: The field circles the wire. Curl is nonzero along the wire (where current flows) and zero elsewhere.

Physical Interpretations

Fluid flow: If F is the velocity field of a fluid, ∇ × F is twice the angular velocity. It measures vorticity—how much the fluid is swirling at each point. Zero curl means irrotational flow.

Electromagnetism: Faraday's law says ∇ × E = -∂B/∂t. The curl of the electric field equals the rate of change of the magnetic field. Changing magnetic fields create swirling electric fields.

Ampère-Maxwell law says ∇ × B = μ₀J + μ₀ε₀∂E/∂t. The curl of the magnetic field is driven by current and changing electric fields.

General: Curl is the infinitesimal version of circulation. It's local circulation density—circulation per unit area at a point.

Example: Rotating Field

Consider F(x, y, z) = (-y, x, 0).

∂R/∂y - ∂Q/∂z = ∂(0)/∂y - ∂(x)/∂z = 0 ∂P/∂z - ∂R/∂x = ∂(-y)/∂z - ∂(0)/∂x = 0 ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y = ∂(x)/∂x - ∂(-y)/∂y = 1 - (-1) = 2

So ∇ × F = (0, 0, 2).

The curl points in the +z direction with magnitude 2. This makes sense: the field rotates counterclockwise in the xy-plane, so the rotation axis is the z-axis. The magnitude 2 comes from the fact that the field has constant angular velocity ω = 1, and curl is 2ω for rigid rotation.

Curl-Free Fields

A field with ∇ × F = 0 everywhere is called curl-free or irrotational.

Curl-free fields are gradients: F = ∇φ for some scalar potential φ.

Examples:

- Gravitational fields (F = ∇U, where U is gravitational potential)

- Electrostatic fields (E = -∇V, where V is voltage)

- Any conservative force field

Curl-free fields have no circulation. Line integrals around closed loops are zero. The field is path-independent—you can define a potential function whose gradient is the field.

If ∇ × F ≠ 0, the field is not conservative. You can't write it as a gradient. Line integrals depend on the path. There's circulation.

The Curl Formula

In Cartesian coordinates:

∇ × F = det | i j k | | ∂/∂x ∂/∂y ∂/∂z | | P Q R |

This determinant notation is mnemonic. Expand it like a 3×3 determinant:

i (∂R/∂y - ∂Q/∂z) - j (∂R/∂x - ∂P/∂z) + k (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y)

Which is the same as the component formula given earlier.

In other coordinate systems, curl is more complicated because basis vectors change with position.

Cylindrical (r, θ, z): ∇ × F = (1/r ∂F_z/∂θ - ∂F_θ/∂z, ∂F_r/∂z - ∂F_z/∂r, 1/r (∂(rF_θ)/∂r - ∂F_r/∂θ))

Spherical (r, θ, φ): Even messier. Use the general formula in terms of basis vectors and metric tensor, or look it up in a reference.

For most problems, choose coordinates that make the field simple. Symmetry is your friend.

Computing Curl: Example

Let F = (yz, xz, xy).

∂R/∂y - ∂Q/∂z = ∂(xy)/∂y - ∂(xz)/∂z = x - x = 0 ∂P/∂z - ∂R/∂x = ∂(yz)/∂z - ∂(xy)/∂x = y - y = 0 ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y = ∂(xz)/∂x - ∂(yz)/∂y = z - z = 0

∇ × F = (0, 0, 0). The field is curl-free, even though it looks complicated. This means F is conservative—it's the gradient of some potential. (In fact, F = ∇(xyz).)

Stokes' Theorem

Stokes' Theorem is the fundamental theorem for curl:

∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = ∫_C F · dr

The surface integral of curl over a surface S equals the line integral of F around the boundary curve C.

This connects local and global: integrating rotation over a surface gives the circulation around the edge.

It's the 3D generalization of Green's Theorem. Instead of ∫∫ curl dA = ∫ F · dr in 2D, you have ∫∫ (∇ × F) · dS = ∫ F · dr in 3D.

The theorem transforms surface integrals into line integrals or vice versa. It also reveals that curl-free fields (∇ × F = 0) have zero circulation around any closed loop.

Curl and Rotation

For a rigid body rotating with angular velocity ω, the velocity field is v = ω × r.

The curl of this velocity field is:

∇ × v = 2ω

Curl is twice the angular velocity. This is a general result: for any rigidly rotating flow, curl = 2ω.

In fluid dynamics, vorticity is defined as ω = ∇ × v (with the factor of 2 absorbed). Vorticity measures the local spinning of the fluid. Tornadoes, whirlpools, and turbulent eddies all have high vorticity.

The Right-Hand Rule

Curl is a vector, and its direction follows the right-hand rule.

If the field circulates counterclockwise (viewed from above), the curl points upward. If it circulates clockwise, the curl points downward.

Curl your right hand in the direction of circulation. Your thumb points in the direction of the curl vector.

This convention ensures consistency with cross products and with the orientation of surfaces in Stokes' Theorem.

Relationship to Divergence

Divergence and curl are complementary operators. Divergence measures spreading (a scalar). Curl measures rotation (a vector).

Key identity: for any vector field F:

∇ · (∇ × F) = 0

The divergence of a curl is always zero. This is algebraically provable from the definitions.

Why? Because curls produce circulating fields with no sources or sinks. Field lines form closed loops, so divergence vanishes.

Conversely, if ∇ · F = 0, then (under suitable conditions) F = ∇ × G for some vector potential G. Divergence-free fields are curls.

Another identity: for any scalar φ:

∇ × (∇φ) = 0

The curl of a gradient is always zero. Gradients are curl-free. This is why conservative fields (which are gradients) have no circulation.

Curl in Maxwell's Equations

Two of Maxwell's equations are curl equations:

∇ × E = -∂B/∂t (Faraday's law) ∇ × B = μ₀J + μ₀ε₀∂E/∂t (Ampère-Maxwell law)

Faraday's law: A changing magnetic field creates a curling electric field. This is electromagnetic induction—the principle behind generators and transformers.

Ampère-Maxwell law: Electric current and changing electric fields create a curling magnetic field. This is how electromagnets work and how electromagnetic waves propagate.

Together with the divergence equations (∇ · E = ρ/ε₀ and ∇ · B = 0), these four equations completely determine electromagnetic fields.

Curl is essential. Without it, you can't describe Faraday's law or Ampère's law. You can't formulate electromagnetism.

Helmholtz Decomposition

Any sufficiently nice vector field F can be uniquely decomposed as:

F = -∇φ + ∇ × A

where φ is a scalar potential and A is a vector potential.

The first term (-∇φ) is curl-free (irrotational). The second term (∇ × A) is divergence-free (solenoidal).

This is the Helmholtz decomposition. It says every field is the sum of a gradient part (responsible for divergence) and a curl part (responsible for rotation).

In electromagnetism:

- Electric field: E = -∇V - ∂A/∂t

- Magnetic field: B = ∇ × A

The scalar potential V and vector potential A are the fundamental objects. E and B are derived from them.

Visualizing Curl

How do you see curl in a vector field plot?

Look for circulation. If field vectors swirl around a point or axis, there's nonzero curl.

In a 2D plot, curl points perpendicular to the plane (in or out). You see it as circulation in the plane.

In a 3D plot, curl can point in any direction. Field lines might twist around the curl vector.

Examples:

- Whirlpool: vectors circle around a center. High curl at the center, decreasing outward.

- Shear flow: parallel flow with different speeds at different heights. This has curl perpendicular to the flow direction.

- Uniform flow: all vectors parallel and equal. Zero curl.

Curl and Conservative Fields

A field is conservative if and only if it's curl-free.

F is conservative ⟺ F = ∇φ for some φ ⟺ ∇ × F = 0

Conservative fields have path-independent line integrals. The work done moving from A to B doesn't depend on the path.

Non-conservative fields have nonzero curl somewhere. Work depends on the path. Energy can be extracted from circulation (or must be supplied to maintain circulation).

Testing for conservativeness: compute curl. If ∇ × F = 0 everywhere, the field is conservative. Find φ by integrating. If ∇ × F ≠ 0, the field is not conservative—there's no global potential.

Irrotational Flow

In fluid dynamics, irrotational flow means ∇ × v = 0.

This occurs when the fluid has no vorticity—no local spinning. The flow is smooth and laminar, with no eddies or turbulence.

Irrotational flow is often assumed in aerodynamics and hydrodynamics because it simplifies the equations enormously. You can introduce a velocity potential φ with v = ∇φ, turning the problem into scalar potential theory.

Real fluids aren't always irrotational (viscosity and boundaries create vorticity), but irrotational flow is a useful approximation.

Curl and Magnetic Vector Potential

In electromagnetism, the magnetic field is always divergence-free: ∇ · B = 0.

This means B can be written as the curl of a vector potential A:

B = ∇ × A

The vector potential A is not unique (you can add a gradient to A without changing B), but it's a fundamental object in quantum mechanics and in gauge theories.

Faraday's law (∇ × E = -∂B/∂t) can be rewritten using A:

∇ × (E + ∂A/∂t) = 0

This means E + ∂A/∂t is curl-free, so:

E = -∇V - ∂A/∂t

where V is the electric potential. This is the full relationship between E, B, and the potentials V and A.

The potentials are primary. The fields are derived. Curl and gradient connect them.

Why Curl Matters

Curl is one of the three core differential operators in vector calculus (with gradient and divergence). It appears in:

- Maxwell's equations (two of four are curl equations)

- Fluid dynamics (vorticity and circulation)

- Stokes' Theorem (fundamental theorem connecting surface and line integrals)

- Helmholtz decomposition (splitting fields into irrotational and solenoidal parts)

- Gauge theories in quantum field theory

Without curl, you can't describe rotation, circulation, or electromagnetic induction. You can't formulate Faraday's law or Ampère's law. You can't analyze vortices or turbulence.

Curl is as fundamental as divergence. Divergence detects sources. Curl detects rotation. Together, they characterize the local structure of vector fields completely.

Understanding curl geometrically—what it measures, why it appears in Maxwell's equations, how it connects to circulation via Stokes' Theorem—is essential for mastering vector calculus and the physics it describes.

Next, we'll unify gradient, divergence, and curl under a single operator: del (∇). This will reveal the algebraic structure underlying vector calculus and clarify how these three operators are related.

Part 6 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: Divergence: How Much Does a Field Spread Out? Next: The Gradient Curl and Divergence: Del Operations

Comments ()