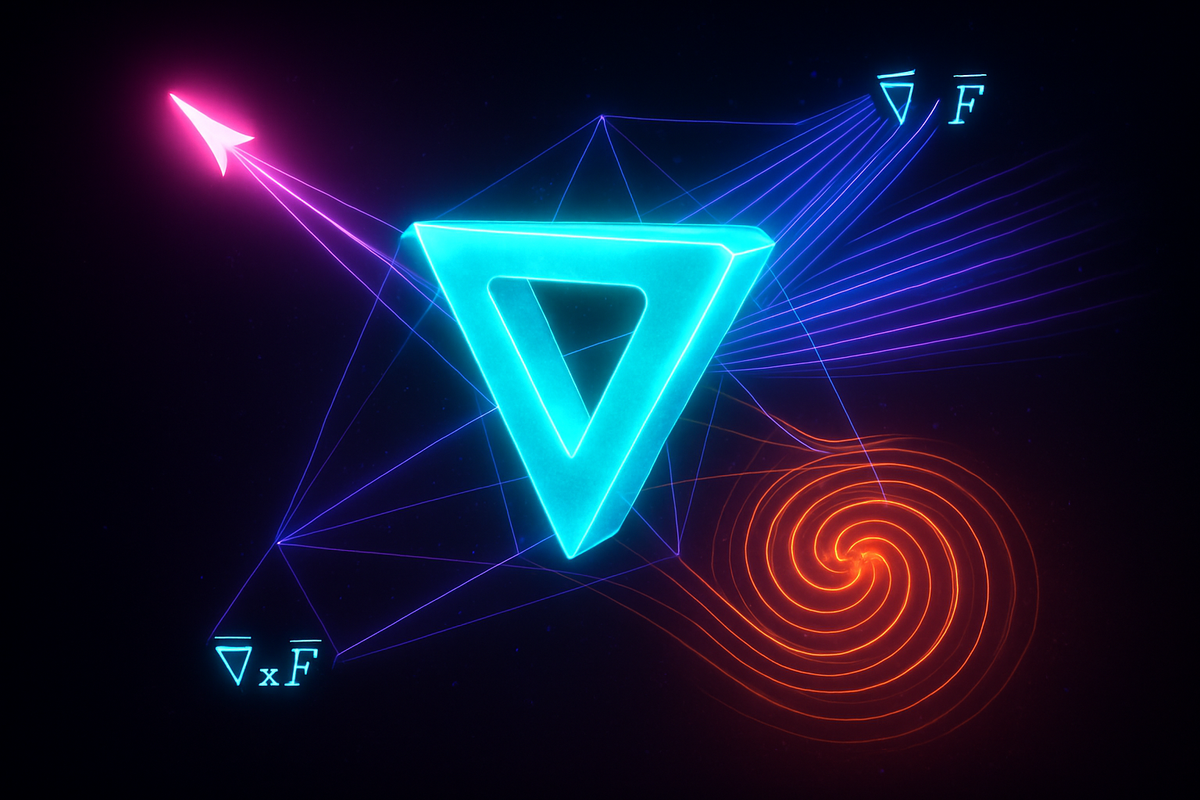

The Gradient Curl and Divergence: Del Operations

The del operator—written ∇ and pronounced "nabla" or "del"—is the unifying symbol of vector calculus. It's a vector of partial derivatives that generates gradient, divergence, and curl depending on how you apply it. Think of it as a mathematical Swiss Army knife: one symbol, three operations.

In Cartesian coordinates:

∇ = (∂/∂x, ∂/∂y, ∂/∂z)

It looks like a vector, but its components are operators, not numbers. When you apply ∇ to a scalar field, a vector field, or combine it with vector operations, you get the fundamental differential operators.

This notation isn't just convenient shorthand. It reveals algebraic structure. Gradient, divergence, and curl aren't arbitrary definitions—they're natural products of the del operator acting in different ways.

Gradient: Del Applied to a Scalar

When you apply ∇ to a scalar field φ, you get the gradient:

∇φ = (∂φ/∂x, ∂φ/∂y, ∂φ/∂z)

This is a vector field that points in the direction of steepest increase of φ, with magnitude equal to the rate of increase.

The notation makes sense: you're "multiplying" the vector operator ∇ by the scalar φ, producing a vector field.

Example: φ(x, y, z) = x² + y² + z²

∇φ = (2x, 2y, 2z) = 2(x, y, z)

The gradient points radially outward from the origin, which is the direction of steepest increase for this function.

Divergence: Del Dotted with a Vector

When you take the dot product of ∇ with a vector field F = (P, Q, R), you get divergence:

∇ · F = ∂P/∂x + ∂Q/∂y + ∂R/∂z

This is a scalar field that measures how much the field spreads out at each point.

The notation makes sense: you're taking the dot product of the vector operator ∇ with the vector field F. Dot products produce scalars, and divergence is a scalar.

Example: F = (x², y², z²)

∇ · F = ∂(x²)/∂x + ∂(y²)/∂y + ∂(z²)/∂z = 2x + 2y + 2z

Divergence increases as you move away from the origin.

Curl: Del Crossed with a Vector

When you take the cross product of ∇ with a vector field F = (P, Q, R), you get curl:

∇ × F = (∂R/∂y - ∂Q/∂z, ∂P/∂z - ∂R/∂x, ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y)

This is a vector field that measures rotation at each point.

The notation makes sense: you're taking the cross product of the vector operator ∇ with the vector field F. Cross products produce vectors, and curl is a vector.

Example: F = (-y, x, 0)

∇ × F = (∂(0)/∂y - ∂(x)/∂z, ∂(-y)/∂z - ∂(0)/∂x, ∂(x)/∂x - ∂(-y)/∂y) = (0, 0, 1 + 1) = (0, 0, 2)

The curl points in the +z direction with magnitude 2, matching the counterclockwise rotation of the field.

The Algebraic Unification

Here's why the del notation is powerful: it treats gradient, divergence, and curl as instances of the same algebraic operation.

- Gradient: ∇ acting on a scalar → vector

- Divergence: ∇ · (vector) → scalar

- Curl: ∇ × (vector) → vector

The same operator, three different contexts. You don't need to memorize three separate definitions—you just need to understand how ∇ interacts with scalars and vectors.

This unification extends to second-order operators:

- Laplacian: ∇ · (∇φ) = ∇²φ (divergence of gradient)

- Curl of curl: ∇ × (∇ × F) (appears in wave equations)

- Divergence of curl: ∇ · (∇ × F) = 0 (always zero)

- Curl of gradient: ∇ × (∇φ) = 0 (always zero)

These identities follow from the algebraic properties of ∇, treated as if it were a vector.

The Laplacian

The Laplacian is ∇² = ∇ · ∇, applied to a scalar field:

∇²φ = ∂²φ/∂x² + ∂²φ/∂y² + ∂²φ/∂z²

It's the sum of second partial derivatives—a measure of curvature or "how much φ differs from its average nearby."

The Laplacian appears everywhere in physics:

- Heat equation: ∂T/∂t = α∇²T (temperature diffuses according to Laplacian)

- Wave equation: ∂²u/∂t² = c²∇²u (waves propagate according to Laplacian)

- Schrödinger equation: iℏ∂ψ/∂t = -ℏ²/(2m)∇²ψ + Vψ (quantum wavefunctions evolve via Laplacian)

- Poisson's equation: ∇²φ = ρ (potential φ determined by source density ρ)

The Laplacian is the divergence of the gradient: ∇ · (∇φ). It combines two del operations, measuring how the gradient field spreads.

Vector Identities via Del

Many vector calculus identities become transparent when written with del notation.

Divergence of curl is zero: ∇ · (∇ × F) = 0

This follows because dot product and cross product satisfy a · (a × b) = 0 (a is perpendicular to a × b). Treating ∇ as a vector, the identity holds.

Curl of gradient is zero: ∇ × (∇φ) = 0

This follows because a × a = 0 for any vector a. Taking the cross product of ∇ with itself (applied to φ) gives zero.

Curl of curl identity: ∇ × (∇ × F) = ∇(∇ · F) - ∇²F

This is analogous to the vector identity a × (b × c) = b(a · c) - c(a · b). The Laplacian ∇²F is applied component-wise to the vector field.

These aren't separate facts to memorize—they're consequences of treating ∇ algebraically.

Del in Different Coordinate Systems

In Cartesian coordinates, ∇ = (∂/∂x, ∂/∂y, ∂/∂z). But in other coordinate systems, the formula changes.

Cylindrical (r, θ, z): ∇ = (∂/∂r, 1/r ∂/∂θ, ∂/∂z)

(But this is only part of the story—basis vectors also depend on position, so you need to account for their derivatives.)

Spherical (r, θ, φ): ∇ = (∂/∂r, 1/r ∂/∂θ, 1/(r sin θ) ∂/∂φ)

Again, this is simplified; the full expressions for gradient, divergence, and curl in these coordinates are more complex because basis vectors vary.

The key point: ∇ adapts to the coordinate system, but the conceptual meaning (gradient, divergence, curl) remains the same. The formulas look different, but they measure the same geometric properties.

Physical Meaning of Del

∇φ points toward where φ increases. It's the direction you should walk to climb uphill in the φ landscape.

∇ · F measures whether F is spreading out (positive), converging (negative), or neutral (zero). It's the source/sink detector.

∇ × F measures whether F is rotating (nonzero) or irrotational (zero). It's the vorticity detector.

These are geometric properties of fields, and del is the notation that makes them algebraically consistent.

Del as a Differential Operator

Formally, ∇ is a differential operator—a machine that takes functions to functions (or vector fields to scalar/vector fields).

As an operator, ∇ is linear:

∇(φ + ψ) = ∇φ + ∇ψ ∇(cφ) = c∇φ

It obeys the product rule:

∇(φψ) = φ∇ψ + ψ∇φ

And it satisfies chain rules for compositions.

This operator perspective is essential in functional analysis, differential geometry, and quantum mechanics. You're not just "taking derivatives"—you're applying a linear transformation to a function space.

Directional Derivatives

The gradient ∇φ also appears in directional derivatives.

The rate of change of φ in the direction of a unit vector u is:

D_u φ = ∇φ · u

This is the dot product of the gradient with the direction. It projects the gradient onto the direction u, giving the rate of change in that direction.

Maximizing D_u φ over all unit vectors u gives |∇φ|, achieved when u points along ∇φ. That's why gradient points in the direction of steepest increase.

Del and the Fundamental Theorems

The three fundamental theorems of vector calculus (Green's, Stokes', Divergence) all involve del:

Green's Theorem: ∫∫_R (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y) dA = ∫_C (P, Q) · dr

The integrand on the left is the 2D curl: ∇ × F = ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y (in 2D, curl is a scalar).

Stokes' Theorem: ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = ∫_C F · dr

Surface integral of curl equals line integral around boundary.

Divergence Theorem: ∫∫∫_V (∇ · F) dV = ∫∫_S F · dS

Volume integral of divergence equals surface integral over boundary.

All three theorems relate a del operation inside a region to a boundary integral. They're all instances of the general Stokes' Theorem in differential geometry, but the del notation makes the structure visible in each case.

Del in Maxwell's Equations

Maxwell's equations are pure del:

∇ · E = ρ/ε₀ ∇ · B = 0 ∇ × E = -∂B/∂t ∇ × B = μ₀J + μ₀ε₀∂E/∂t

Two divergence equations, two curl equations. The del operator is the grammatical structure of electromagnetism.

Without del notation, these equations would be written in components with 12 partial derivatives scattered across multiple equations. The del notation reveals the geometric unity.

Why Del Matters

Del is more than notation. It's a conceptual unification.

Gradient, divergence, and curl aren't three separate ideas—they're three manifestations of the same differential operator acting on different objects.

The algebraic properties of del (linearity, product rules, vector algebra) translate directly into properties of gradient, divergence, and curl.

The fundamental theorems are all del-based: they relate del operations to boundary integrals.

Maxwell's equations, the Navier-Stokes equations, the Schrödinger equation—all written with del. It's the language of field theory.

Understanding del means understanding that vector calculus isn't a collection of formulas. It's a coherent algebraic system built on a single operator. Once you internalize ∇, the rest follows.

Computational Notes

When computing with del:

Gradient: Apply ∇ to a scalar. Take partial derivatives in each direction.

Divergence: Dot ∇ with a vector field. Sum the diagonal partials (∂P/∂x + ∂Q/∂y + ∂R/∂z).

Curl: Cross ∇ with a vector field. Use the determinant formula or compute components.

Laplacian: Apply ∇² to a scalar. Sum second partials.

In other coordinate systems, look up the formulas (they're messy) or use the geometric definitions (flux per volume for divergence, circulation per area for curl).

Del and Differential Forms

In differential geometry, del is replaced by exterior derivatives and differential forms. The gradient, curl, and divergence are all special cases of the exterior derivative d.

This perspective unifies vector calculus with topology and geometry, extending it to manifolds, gauge theories, and modern physics.

But for classical vector calculus in R³, del is the perfect notation. It's intuitive, algebraically consistent, and physically transparent.

The Bigger Picture

Vector calculus rests on three pillars:

- Vector fields (the objects)

- Del operator (the operations)

- Fundamental theorems (the connections)

Del is the middle pillar. It takes vector fields and extracts their differential properties—gradient, divergence, curl, Laplacian.

The fundamental theorems connect these local differential properties to global integral properties—boundaries, surfaces, volumes.

Together, the three pillars form a complete system for describing fields, flows, forces, and fluxes.

Del is the keystone. Master it, and the rest of vector calculus becomes a coherent whole.

Part 7 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: Curl: How Much Does a Field Rotate? Next: Green's Theorem: Relating Line and Double Integrals

Comments ()