Derivatives of Trigonometric Functions: Why d/dx(sin x) = cos x

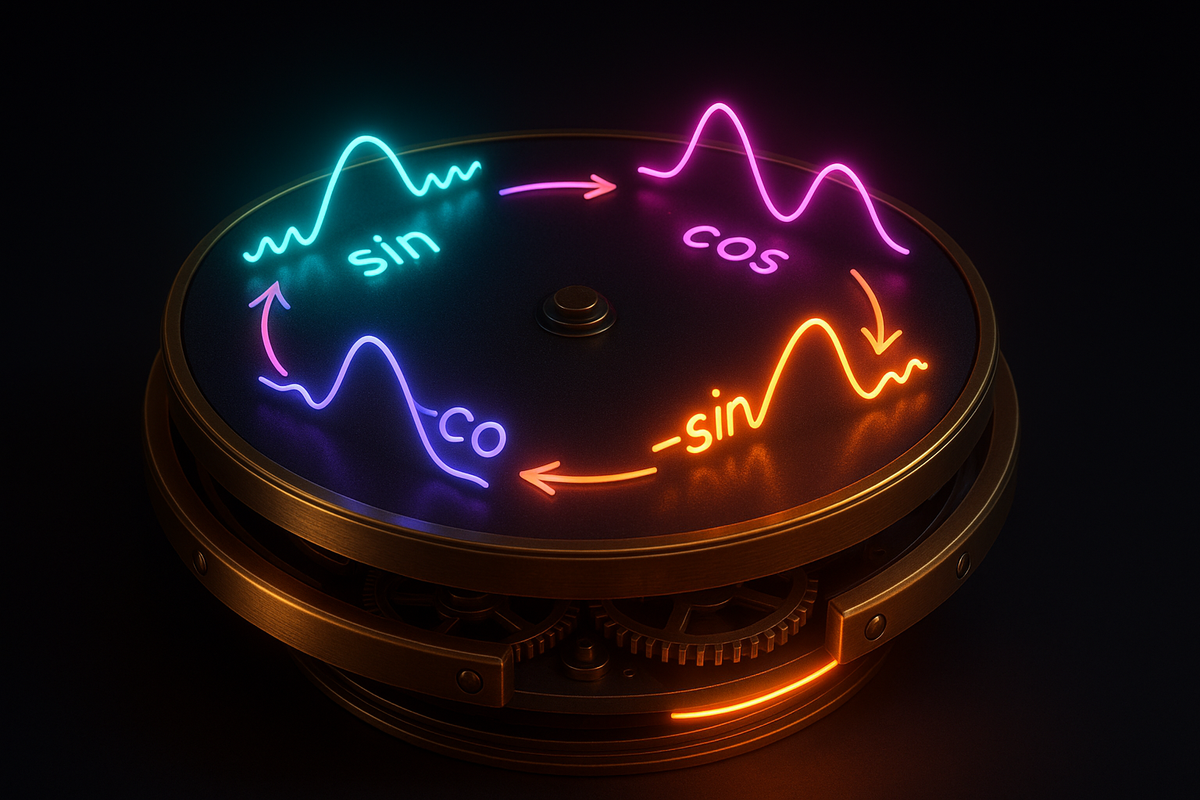

The trig derivatives form a beautiful cycle:

d/dx(sin x) = cos x d/dx(cos x) = -sin x d/dx(-sin x) = -cos x d/dx(-cos x) = sin x

Then it repeats. Four derivatives to complete the loop.

Here's the unlock: this cycle isn't arbitrary — it comes from the geometry of rotation. When a point moves around a circle, its vertical velocity (derivative of sine) is proportional to its horizontal position (cosine). The derivatives encode how position and velocity relate on a rotating wheel.

The Fundamental Derivatives

d/dx(sin x) = cos x

d/dx(cos x) = -sin x

These are the two you need. Everything else follows.

Why d/dx(sin x) = cos x

From the limit definition:

d/dx(sin x) = lim[h→0] (sin(x+h) - sin(x))/h

Use the angle addition formula: sin(x+h) = sin x cos h + cos x sin h

= lim[h→0] (sin x cos h + cos x sin h - sin x)/h = lim[h→0] [sin x(cos h - 1)/h + cos x (sin h)/h] = sin x · lim[h→0] (cos h - 1)/h + cos x · lim[h→0] (sin h)/h

Key limits (provable geometrically):

- lim[h→0] (sin h)/h = 1

- lim[h→0] (cos h - 1)/h = 0

Therefore: = sin x · 0 + cos x · 1 = cos x

Why d/dx(cos x) = -sin x

Similarly:

d/dx(cos x) = lim[h→0] (cos(x+h) - cos(x))/h

Use: cos(x+h) = cos x cos h - sin x sin h

= lim[h→0] (cos x cos h - sin x sin h - cos x)/h = lim[h→0] [cos x(cos h - 1)/h - sin x(sin h)/h] = cos x · 0 - sin x · 1 = -sin x

The negative sign appears because cosine decreases when sine increases (in the first quadrant).

Geometric Intuition

On the unit circle at angle θ:

- x-coordinate = cos θ

- y-coordinate = sin θ

As θ increases (counterclockwise rotation):

- sin θ (height) increases when cos θ (horizontal position) is positive

- cos θ (horizontal) decreases when sin θ (height) is positive

The rate of change of height equals horizontal position. The rate of change of horizontal position equals negative height.

That's the circle's geometry encoded in derivatives.

The Other Four

d/dx(tan x) = sec²x

Prove it: tan x = sin x / cos x. Use quotient rule:

= (cos x · cos x - sin x · (-sin x)) / cos²x = (cos²x + sin²x) / cos²x = 1/cos²x = sec²x

d/dx(cot x) = -csc²x

d/dx(sec x) = sec x tan x

d/dx(csc x) = -csc x cot x

Pattern: Derivatives of "Co-" Functions

Notice the negatives:

- d/dx(sin x) = cos x (positive)

- d/dx(cos x) = -sin x (negative)

- d/dx(tan x) = sec²x (positive)

- d/dx(cot x) = -csc²x (negative)

- d/dx(sec x) = sec x tan x (positive)

- d/dx(csc x) = -csc x cot x (negative)

The "co-" functions (cosine, cotangent, cosecant) all have negative derivatives. The others don't.

Derivatives of Inverse Trig Functions

d/dx(arcsin x) = 1/√(1-x²)

d/dx(arccos x) = -1/√(1-x²)

d/dx(arctan x) = 1/(1+x²)

d/dx(arccot x) = -1/(1+x²)

d/dx(arcsec x) = 1/(|x|√(x²-1))

d/dx(arccsc x) = -1/(|x|√(x²-1))

These come from implicit differentiation. For y = arcsin x: sin y = x, so cos y · dy/dx = 1, giving dy/dx = 1/cos y = 1/√(1-sin²y) = 1/√(1-x²).

Chain Rule Applications

For sin(f(x)):

d/dx(sin(f(x))) = cos(f(x)) · f'(x)

Examples:

d/dx(sin(3x)) = cos(3x) · 3 = 3cos(3x)

d/dx(cos(x²)) = -sin(x²) · 2x = -2x sin(x²)

d/dx(tan(eˣ)) = sec²(eˣ) · eˣ = eˣ sec²(eˣ)

Why Radians?

In radians, d/dx(sin x) = cos x exactly.

In degrees, d/dx(sin x°) = (π/180) cos x°.

The factor π/180 appears because degrees are an arbitrary human convention. Radians are the natural measure where arc length equals radius × angle.

Calculus with trig only works cleanly in radians.

Higher Derivatives of Sine

d/dx(sin x) = cos x d²/dx²(sin x) = -sin x d³/dx³(sin x) = -cos x d⁴/dx⁴(sin x) = sin x (back to start)

The cycle repeats every four derivatives. This pattern reflects the four-fold symmetry of rotation by 90°.

Applications

Simple harmonic motion: x(t) = A sin(ωt) Velocity: v(t) = Aω cos(ωt) Acceleration: a(t) = -Aω² sin(ωt) = -ω²x(t)

The acceleration is proportional to negative position — that's the definition of harmonic motion.

Wave equations: The derivatives of sine describe how waves propagate.

AC circuits: Voltage and current in AC are sinusoidal; their derivatives describe impedance relationships.

The Core Insight

The derivatives of trig functions cycle because trig functions describe circular motion.

d/dx(sin x) = cos x says: the rate of change of vertical position equals horizontal position. That's geometry — when you're at the rightmost point of a circle, your vertical velocity is maximum.

The trig derivatives aren't formulas to memorize. They're the calculus translation of how things move in circles.

sin → cos → -sin → -cos → sin

Round and round. The derivative keeps the rotation going.

Part 10 of the Calculus Derivatives series.

Previous: The Derivative of eˣ: The Function That Is Its Own Rate of Change Next: Optimization: Finding Maxima and Minima with Derivatives

Comments ()