Determinants: The Volume-Scaling Factor of Matrices

The determinant is one number that tells you everything important about a matrix.

How much does the transformation scale volume? Is the transformation reversible? Does it flip orientation? The determinant answers all of these.

It's not a calculation you memorize. It's a property you understand.

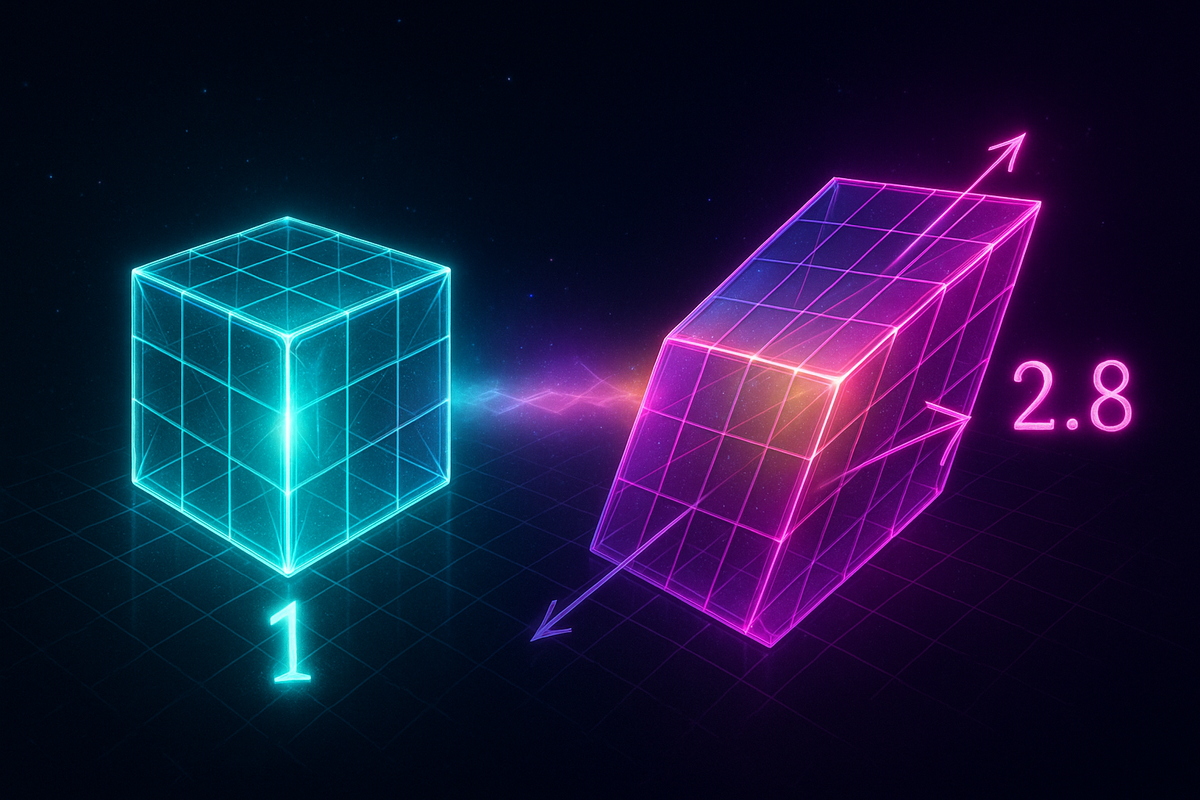

The Geometric Meaning

Take a unit square—corners at (0,0), (1,0), (0,1), and (1,1). Area = 1.

Now apply a 2×2 matrix transformation. The square becomes a parallelogram.

The determinant is the signed area of that parallelogram.

Signed because orientation matters:

- Positive determinant: the transformation preserves handedness (counterclockwise stays counterclockwise)

- Negative determinant: the transformation reverses handedness (counterclockwise becomes clockwise)

- Zero determinant: the parallelogram has collapsed to a line or point—area = 0

For a 3×3 matrix, the determinant is the signed volume of what happens to a unit cube. Same principle, one dimension higher.

The 2×2 Formula

For a 2×2 matrix:

| a b |

| c d |

det = ad - bc

That's it. Multiply the diagonals, subtract.

Let's see why geometrically.

The matrix sends ê₁ = (1,0) to (a,c) and ê₂ = (0,1) to (b,d).

The unit square becomes a parallelogram with sides (a,c) and (b,d).

The area of a parallelogram with sides (a,c) and (b,d) is |ad - bc|.

The sign tells you whether the transformation preserved or reversed orientation.

What Determinant = 0 Means

If det = 0, the transformation collapses at least one dimension.

A unit square with area 1 becomes a parallelogram with area 0. That's a line (or a point).

Geometrically: the two column vectors are parallel. They point in the same (or opposite) direction. There's no "second dimension" after the transformation.

Algebraically: the matrix is not invertible. You can't undo a transformation that loses dimensions. The information is gone.

This is the key test for invertibility:

- det ≠ 0 → invertible

- det = 0 → not invertible

The 3×3 Formula

For larger matrices, the formula gets more complex. For 3×3:

| a b c |

| d e f |

| g h i |

det = a(ei - fh) - b(di - fg) + c(dh - eg)

This is "expansion by minors" along the first row. Each entry in the first row multiplies the determinant of the 2×2 matrix left over when you cross out that row and column.

The pattern generalizes to n×n matrices (with alternating signs and recursion), but the computation grows factorially. For large matrices, use row reduction or numerical algorithms.

Properties of Determinants

Multiplicativity

det(AB) = det(A) × det(B)

The volume scaling of combined transformations equals the product of individual scalings.

If A scales volume by 3 and B scales volume by 2, then AB scales volume by 6.

This is why determinants are useful: they convert matrix multiplication into number multiplication.

Transpose

det(Aᵀ) = det(A)

The transpose doesn't change the determinant. Rows and columns contribute equally.

Inverse

det(A⁻¹) = 1/det(A)

The inverse transformation scales volume by the reciprocal factor.

If A doubles volume, A⁻¹ halves it.

Row Operations

- Swapping two rows: flips the sign of the determinant

- Multiplying a row by scalar k: multiplies determinant by k

- Adding a multiple of one row to another: doesn't change determinant

These properties make row reduction a practical way to compute determinants.

Applications

Checking Invertibility

det(A) ≠ 0 ⟺ A is invertible

This is the primary application. Before trying to invert a matrix, check if it's possible.

Solving Systems of Equations

Cramer's Rule uses determinants to solve Ax = b:

xᵢ = det(Aᵢ)/det(A)

where Aᵢ is A with column i replaced by b.

This isn't efficient for large systems, but it proves solutions exist when det(A) ≠ 0.

Change of Variables in Integration

When you change coordinates in a multiple integral, the Jacobian determinant scales the area/volume element.

The integral becomes:

∫∫ f(x,y) dx dy = ∫∫ f(g(u,v)) |det(J)| du dv

where J is the Jacobian matrix of partial derivatives.

Cross Product

In 3D, the cross product a × b can be computed as a determinant:

| î ĵ k̂ |

| a₁ a₂ a₃ |

| b₁ b₂ b₃ |

The result is a vector perpendicular to both a and b, with magnitude equal to the parallelogram area.

Geometric Intuition for Special Cases

Rotation Matrices

Rotation matrices have determinant 1.

Rotation doesn't change area or volume—it just moves things around.

Scaling Matrices

A diagonal scaling matrix:

| k₁ 0 0 |

| 0 k₂ 0 |

| 0 0 k₃ |

has determinant k₁ × k₂ × k₃.

Scale by 2 in each direction: volume scales by 8.

Reflection Matrices

Reflections have determinant -1.

Area is preserved, but orientation is flipped.

Projection Matrices

Projection matrices have determinant 0.

They collapse to a lower dimension—information is lost.

Shear Matrices

Shears have determinant 1.

They distort shape but preserve area. A unit square becomes a parallelogram with the same area.

The Deeper Pattern

The determinant captures something fundamental: how much does the transformation change the "amount" of space?

In 2D, that's area. In 3D, volume. In n dimensions, n-dimensional volume (hypervolume).

Transformations that preserve this quantity (|det| = 1) are special. Rotations and reflections preserve lengths and angles. Volume-preserving transformations are important in physics (incompressible fluids, Hamiltonian mechanics).

The sign captures something equally fundamental: does the transformation preserve or reverse orientation? This matters in physics (parity), topology, and computer graphics (backface culling).

Computing Determinants Efficiently

For 2×2: use the formula ad - bc.

For 3×3: expansion by minors works, but row reduction is often faster.

For larger matrices:

- Row reduce to triangular form

- Determinant of triangular matrix = product of diagonal entries

- Track sign changes from row swaps

For numerical computation, LU decomposition finds det efficiently and stably.

What's Next

The determinant tells you how much space scales. But it doesn't tell you which directions scale.

Some special directions don't just scale—they survive the transformation unchanged except for stretching. These are eigenvectors, and their scaling factors are eigenvalues.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors are where linear algebra gets really powerful. They reveal the intrinsic structure of a transformation, independent of coordinates.

That's next.

This is Part 5 of the Linear Algebra series. Next: "Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors: The Directions That Do Not Rotate."

Part 5 of the Linear Algebra series.

Previous: Matrix Multiplication: Why the Rows and Columns Dance Next: Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors: The Directions That Do Not Rotate

Comments ()