The Divergence Theorem: From Surface Flux to Volume Sources

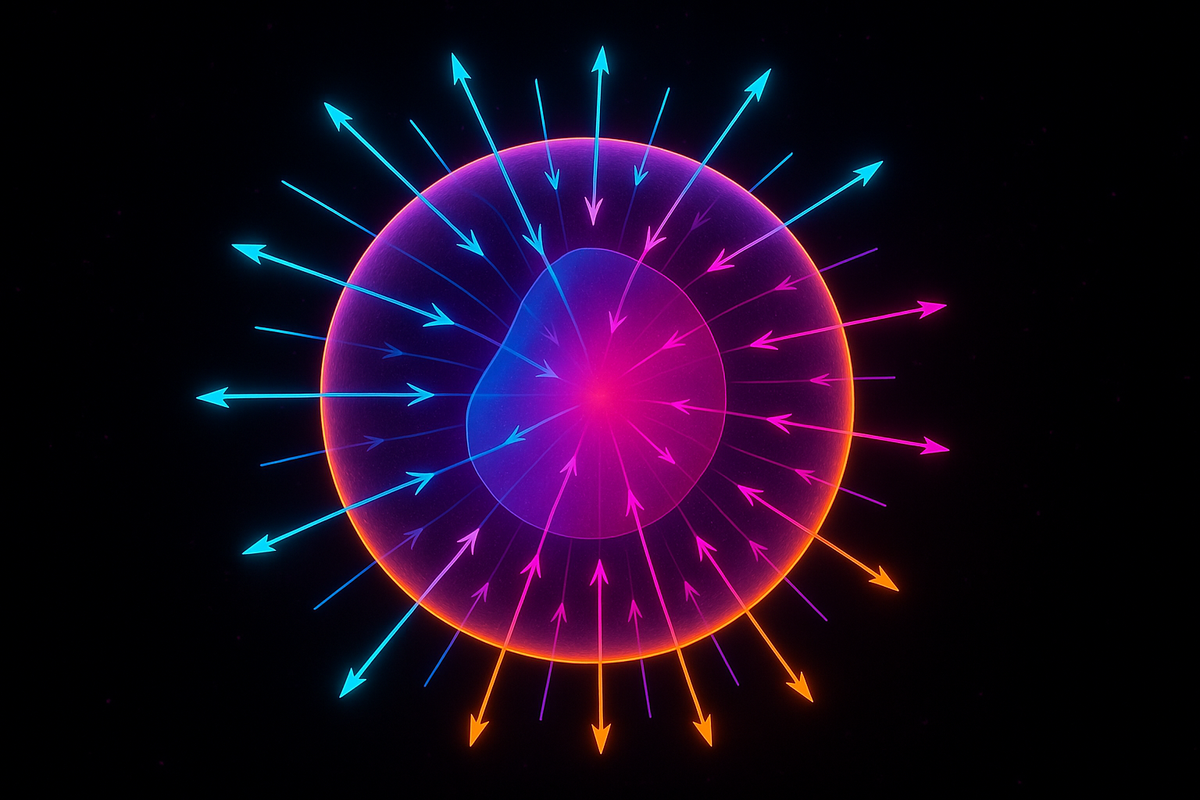

The Divergence Theorem (also called Gauss's Theorem) connects a surface integral over a closed surface to a volume integral over the region it encloses. It says: the flux out of the boundary equals the total divergence inside.

∫∫_S F · dS = ∫∫∫_V (∇ · F) dV

where S is a closed surface, V is the volume it encloses, and F is a vector field in 3D.

This is the fundamental theorem for divergence. Flux through the boundary equals integrated source density in the interior. What flows out must be created inside.

The theorem transforms hard surface integrals into easier volume integrals (or vice versa). It also reveals conservation laws: if ∇ · F = 0 (no sources), then flux through any closed surface is zero.

The Setup

You have a closed surface S in 3D space. Think of it as a balloon, a box, a sphere—any surface that completely encloses a volume.

You have the volume V inside S.

You have a vector field F defined in the region.

The Divergence Theorem says:

∫∫_S F · dS = ∫∫∫_V (∇ · F) dV

Surface integral (flux out) = Volume integral (divergence inside).

Why It's True: The Geometric Intuition

Imagine dividing the volume V into tiny boxes. For each box, the flux out of its surface approximately equals the divergence inside (by a local version of the theorem).

Now add up all boxes. The interiors sum to ∫∫∫_V (∇ · F) dV. The surfaces mostly cancel—each internal face is shared by two boxes and traversed in opposite directions. Only the outer surface S survives.

So ∑(flux out of tiny boxes) = ∫∫_S (outer boundary) = ∫∫∫_V divergence.

This is the telescoping idea again. Interior surfaces cancel, leaving only the boundary contribution.

Example: Radial Field Through a Sphere

Let F(x, y, z) = (x, y, z), a radial field pointing outward from the origin.

∇ · F = ∂x/∂x + ∂y/∂y + ∂z/∂z = 1 + 1 + 1 = 3.

Let S be the sphere of radius a centered at the origin.

Surface integral:

On the sphere, the outward unit normal is n = (x, y, z)/a.

F · n = (x, y, z) · (x, y, z)/a = (x² + y² + z²)/a = a²/a = a.

The flux per unit area is a (constant on the sphere).

Surface area of sphere: 4πa².

∫∫_S F · dS = a · 4πa² = 4πa³.

Volume integral:

∫∫∫_V (∇ · F) dV = ∫∫∫_V 3 dV = 3 · (volume of sphere) = 3 · (4πa³/3) = 4πa³.

Both sides equal 4πa³. The Divergence Theorem checks out.

Flux and Divergence

Flux through a surface measures "how much field crosses the surface."

Divergence at a point measures "how much field spreads out from the point."

The Divergence Theorem says: total spreading inside equals total flux out.

If ∇ · F > 0 somewhere, there's a source. Field is being created. Flux out exceeds flux in.

If ∇ · F < 0 somewhere, there's a sink. Field is being destroyed. Flux in exceeds flux out.

If ∇ · F = 0 everywhere, the field is divergence-free (solenoidal). Flux in equals flux out. No sources or sinks.

Applications: Gauss's Law

Gauss's law in electrostatics:

∫∫S E · dS = Q{enclosed} / ε₀

The flux of the electric field through a closed surface equals the enclosed charge (divided by ε₀).

Using the Divergence Theorem:

∫∫∫V (∇ · E) dV = Q{enclosed} / ε₀

If charge density is ρ, then Q_{enclosed} = ∫∫∫_V ρ dV.

So:

∫∫∫_V (∇ · E) dV = (1/ε₀) ∫∫∫_V ρ dV

This holds for any volume V, so the integrands must be equal:

∇ · E = ρ / ε₀

This is the differential form of Gauss's law—one of Maxwell's equations. The divergence of the electric field equals the charge density.

The Divergence Theorem connects the integral form (experimentally observed) to the differential form (the fundamental equation).

Applications: Incompressible Fluid Flow

For a fluid, if the velocity field is v, then ∇ · v measures the rate of volume expansion.

For incompressible flow, ∇ · v = 0 everywhere.

By the Divergence Theorem:

∫∫_S v · dS = ∫∫∫_V (∇ · v) dV = 0

The flux through any closed surface is zero. What flows in must flow out. Volume is conserved.

This is the continuity equation for incompressible fluids. The Divergence Theorem makes the connection between local incompressibility (∇ · v = 0) and global conservation (zero net flux).

Conservation Laws

The Divergence Theorem is the mathematical foundation of every conservation law.

Mass conservation: ∂ρ/∂t + ∇ · (ρv) = 0

Integrate over a volume V and apply the Divergence Theorem:

∫∫∫_V ∂ρ/∂t dV + ∫∫_S (ρv) · dS = 0

The rate of change of total mass inside V equals the negative flux of mass through the boundary. Mass isn't created or destroyed—it just flows.

Charge conservation: ∂ρ/∂t + ∇ · J = 0

Integrate and apply the Divergence Theorem:

∫∫∫_V ∂ρ/∂t dV + ∫∫_S J · dS = 0

The rate of change of total charge equals the negative current out of the boundary. Charge is conserved.

Energy conservation, momentum conservation, etc. all have the same structure. The Divergence Theorem connects local differential equations to global integral statements.

Example: Cube

Let F = (x², y², z²), and let S be the cube [0, 1] × [0, 1] × [0, 1] with outward normal.

Volume integral:

∇ · F = 2x + 2y + 2z

∫∫∫_V (2x + 2y + 2z) dV = ∫_0^1 ∫_0^1 ∫_0^1 (2x + 2y + 2z) dx dy dz

= ∫_0^1 ∫_0^1 [x² + 2xy + 2xz]_0^1 dy dz

= ∫_0^1 ∫_0^1 (1 + 2y + 2z) dy dz

= ∫_0^1 [y + y² + 2yz]_0^1 dz

= ∫_0^1 (2 + 2z) dz

= [2z + z²]_0^1 = 3

Surface integral:

The cube has six faces. For each face, compute F · n and integrate.

Face x = 1 (normal n = (1, 0, 0)): F · n = x² = 1. Area = 1. Contribution: 1. Face x = 0 (normal n = (-1, 0, 0)): F · n = -x² = 0. Contribution: 0. Face y = 1 (normal n = (0, 1, 0)): F · n = y² = 1. Area = 1. Contribution: 1. Face y = 0 (normal n = (0, -1, 0)): F · n = 0. Contribution: 0. Face z = 1 (normal n = (0, 0, 1)): F · n = z² = 1. Area = 1. Contribution: 1. Face z = 0 (normal n = (0, 0, -1)): F · n = 0. Contribution: 0.

Total: 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3.

Both sides equal 3. The Divergence Theorem verified.

Orientation

The surface S must be oriented with the outward-pointing normal for the theorem to hold. If you flip the normal, you flip the sign of the surface integral.

For closed surfaces, "outward" is the standard convention. It ensures consistency and makes the theorem statement clean.

Divergence-Free Fields

If ∇ · F = 0 everywhere, then ∫∫_S F · dS = 0 for any closed surface S.

Examples:

- Magnetic fields: ∇ · B = 0 (no magnetic monopoles). Flux through any closed surface is zero.

- Incompressible fluid flow: ∇ · v = 0. Net flux through any boundary is zero.

- Any field of the form F = ∇ × G (curl of another field). Divergence of curl is always zero.

Divergence-free fields have no sources or sinks. Field lines don't begin or end—they either loop back on themselves or extend to infinity.

Proof Sketch

For a rectangular box, compute the flux through each face using the fundamental theorem of calculus in that direction. Sum over all faces, and you get the integral of divergence over the box.

For general regions, approximate with tiny boxes, apply the theorem to each, sum, and take the limit. Interior faces cancel, leaving only the outer surface.

The proof is essentially the fundamental theorem of calculus applied in each coordinate direction, then combined.

Relationship to Stokes' Theorem

Divergence Theorem: ∫∫∫_V (∇ · F) dV = ∫∫_S F · dS (boundary is a surface)

Stokes' Theorem: ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = ∫_C F · dr (boundary is a curve)

Both connect a del operation over a region to a boundary integral. Divergence Theorem handles 3D volumes with 2D surface boundaries. Stokes' handles 2D surfaces with 1D curve boundaries.

Together with Green's Theorem (2D regions with 1D curve boundaries), they form a unified framework: local differential structure determines boundary behavior.

Gauss's Divergence Theorem vs Gauss's Law

"Gauss's Theorem" and "the Divergence Theorem" are the same thing—the theorem we've been discussing.

"Gauss's Law" is a specific application in electrostatics: ∫∫_S E · dS = Q / ε₀.

Gauss's Law follows from the Divergence Theorem applied to the electric field. Don't confuse the general theorem (Divergence Theorem) with the specific application (Gauss's Law).

Computational Strategy

When should you use the Divergence Theorem?

Surface integral looks hard, volume integral of divergence looks easier: Convert to a volume integral. Often true for spheres, boxes, and symmetric surfaces.

Volume integral looks hard, surface integral looks easier: Less common, but occasionally the surface has enough symmetry to make the flux trivial.

Check if a field is divergence-free: If ∇ · F = 0, flux through any closed surface is zero. This is a powerful constraint.

Physical Intuition

The Divergence Theorem says: if you have sources inside a volume, there must be net flux out of the surface. If you have sinks, there must be net flux in.

This is intuitive. If a region contains a water source (∇ · v > 0), water flows out. If it contains a drain (∇ · v < 0), water flows in. The total flow through the boundary matches the total creation/destruction inside.

In electromagnetism: positive charges create electric field (∇ · E > 0), so field lines radiate out. Negative charges absorb field (∇ · E < 0), so field lines converge. The flux through a surface around a charge equals the charge (Gauss's Law).

Why the Divergence Theorem Matters

The Divergence Theorem is the fundamental theorem for divergence. It reveals that:

- Divergence is the source of flux (local spreading integrates to boundary flux)

- Conservation laws are consequences of zero divergence (∇ · F = 0 ⇒ flux conserved)

- Gauss's Law in electromagnetism is an instance of the theorem

It's essential for:

- Electromagnetism (Gauss's Law, ∇ · E = ρ/ε₀, ∇ · B = 0)

- Fluid dynamics (continuity equation, incompressibility)

- Heat transfer (energy conservation)

- Any field theory with sources and sinks

And it completes the trinity of fundamental theorems: Green's (2D), Stokes' (curl), Divergence (divergence). Together, they unify vector calculus.

Understanding the Divergence Theorem geometrically—why boundary flux equals interior divergence, why it encodes conservation laws—is essential for mastering vector calculus and the physics it describes.

Next, we'll see how all these tools come together in Maxwell's equations, where divergence, curl, and the fundamental theorems unify to describe electromagnetism completely.

Part 10 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: Stokes' Theorem: Generalizing Green's Theorem to Surfaces Next: Maxwell's Equations: Vector Calculus in Electromagnetism

Comments ()