Elite Dynamics and Coherence: Why Leadership Classes Matter

Elite Dynamics and Coherence: Why Leadership Classes Matter

Series: Cliodynamics | Part: 7 of 10

Elites are not the enemy. Elite competition is.

This distinction matters. Every complex society has elites—people who control significant resources, hold political power, or possess high status. This is structural, not moral. Complex societies require coordination, and coordination requires coordination capacity, which concentrates in elite classes.

The question isn't whether elites exist. The question is whether they cooperate or compete, and what happens to everyone else when the answer changes.

In structural-demographic theory, elite cooperation is the single most reliable indicator that a society is in an integrative phase. When elites cooperate—sharing power, respecting norms, compromising on policy, investing in collective goods—the society is stable and functional. When elites compete—fighting for scarce positions, weaponizing popular discontent, breaking norms to gain advantage—the society destabilizes.

Elite overproduction transforms cooperation into competition by creating more aspirants than positions. But the mechanism through which this destabilizes society is more subtle than simple conflict. It operates through coherence breakdown: elite fragmentation propagates through the system, decoupling the components that need to be aligned for society to function.

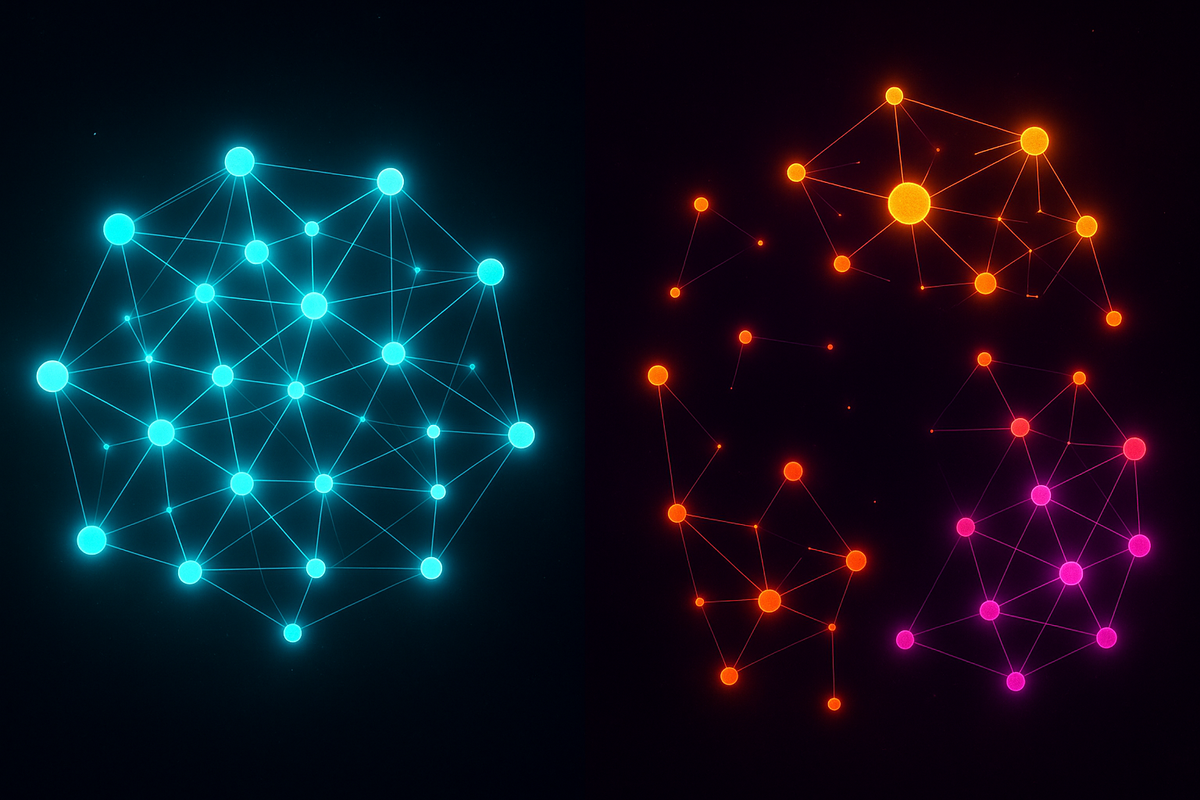

In coherence geometry terms, elites are the coupling hubs—the nodes that coordinate interaction between subsystems. When elites cooperate, they maintain coupling. When they compete, coupling breaks. The society fragments.

Understanding elite dynamics isn't about blaming elites. It's about recognizing their structural role in societal coherence and diagnosing what happens when that role fails.

What Elites Actually Do: The Coordination Function

Elites aren't parasites (though specific elites can be). They perform essential functions:

Coordination Across Subsystems

Complex societies have subsystems—economic, political, military, religious, cultural—that need to be coordinated. Elites sit at the intersection of these subsystems. A senator coordinates between business interests, voters, party apparatus, and state institutions. A CEO coordinates between shareholders, workers, regulators, and markets. A religious leader coordinates between theological tradition, congregation, and broader society.

This coordination isn't automatic. It requires individuals with resources, authority, and networks spanning multiple domains. That's what elites are: coupling nodes in the societal network.

Long-Term Investment and Institution Building

Elites have the resources and timeframe to invest in long-term projects. Infrastructure, universities, legal systems, cultural institutions—these require decades of sustained investment. Individual workers can't build them. Only concentrated resources can.

This is why elite cooperation matters. When elites cooperate, they invest in shared institutions that benefit society broadly. When they compete, they disinvest from shared goods and invest in factional advantage.

Norm Enforcement and Modeling

Elites set behavioral norms through modeling and enforcement. If elites respect rule of law, corruption norms hold. If elites break laws with impunity, corruption spreads. If elites respect democratic transitions, norms of peaceful power transfer hold. If elites contest elections, norms collapse.

This isn't about elites being morally superior. It's about elites being visible. Their behavior is observed, imitated, and interpreted as signal about what's acceptable. When elite cooperation holds, prosocial norms propagate. When elite competition intensifies, antisocial norms propagate.

State Capacity and Fiscal Extraction

States need resources to function. Resources come from extraction (taxation). Effective extraction requires elite cooperation. If elites cooperate with the state, taxation works. If elites resist (through lobbying, evasion, capture), state capacity degrades.

This is why elite fragmentation undermines state capacity. Competing elite factions can't agree on taxation, spending, or regulation. The state becomes paralyzed, revenue declines, capacity collapses. Then the crisis intensifies because the state can't manage it.

Elite Cooperation: How It Works When It Works

During the integrative phase of the secular cycle, elite cooperation dominates. Not because elites are altruistic, but because cooperation serves their interests.

The Conditions for Cooperation

Elite cooperation emerges when:

-

Elite numbers are low relative to positions. There's enough for everyone. You can afford to cooperate because it doesn't cost you your position.

-

Long-term horizons dominate. Elites expect to remain elites, their children to remain elites, their institutions to persist. Investing in collective goods pays off across generations.

-

External threats create common cause. War, economic competition with other societies, or ideological challenge focuses elites on shared goals rather than internal competition.

-

Norms of reciprocity hold. Elites expect others to cooperate if they cooperate. Defection is punished (socially, politically, economically), so cooperation is stable equilibrium.

What Cooperation Produces

When elites cooperate:

- Functional governance: Legislatures pass laws, courts function, bureaucracies operate, transitions are peaceful

- Investment in public goods: Infrastructure, education, research, institutions that benefit broadly

- Norm stability: Rules are respected because elites model compliance

- State capacity: Revenue extraction works, the state can respond to crises

- Social cohesion: Shared narratives hold because elites aren't weaponizing division

This is the geometric configuration of low-curvature societal coherence. The components (population, economy, state, culture) move together because elites provide the coupling that aligns them. Trajectories are smooth because cooperation minimizes friction.

Elite Competition: When Cooperation Collapses

Elite cooperation is stable until the structural conditions that enabled it break down. The primary driver is elite overproduction: more aspirants than positions, creating zero-sum competition.

From Cooperation to Competition

When elite numbers exceed positions:

-

Short-term thinking dominates. If you can't count on remaining elite, you maximize short-term extraction rather than long-term investment.

-

Norm defection becomes rational. If others are competing ruthlessly, cooperating makes you lose. Defection cascades.

-

Factionalism intensifies. Elites cluster into competing groups, weaponizing difference (ideological, regional, cultural) to mobilize support.

-

State capture replaces state cooperation. Rather than investing in state capacity, factions try to capture the state for factional advantage.

What Competition Produces

When elites compete:

- Political paralysis: Factions block each other, governance fails, nothing gets done

- Disinvestment from public goods: Elites hoard resources, avoid taxation, defund shared institutions

- Norm breakdown: Rules are strategic tools, not shared constraints; elites model defection

- State fiscal collapse: Revenue can't be extracted, capacity degrades, crisis response fails

- Narrative fragmentation: Elites weaponize competing stories to mobilize coalitions

This is rising curvature and coherence collapse. The coupling that held subsystems together breaks. Components pursue incompatible trajectories. The society fragments geometrically.

Historical Examples: Elite Cooperation and Competition

Rome: From Cooperation to Civil War

The Roman Republic during the 2nd-3rd centuries BCE showed elite cooperation. The senatorial class was small, powerful families rotated through offices, conquest generated enough spoils to satisfy elite ambitions. Norms of republican virtue held. The state was strong.

By the 1st century BCE, elite overproduction had occurred. More families competing for limited magistracies. Populares vs. Optimates factionalism. Norm breakdown (Sulla's proscriptions, Caesar crossing the Rubicon). State fiscal stress (latifundia, tax farming corruption). The cooperation that sustained the Republic collapsed into civil war.

The resolution was the Principate: Augustus eliminated elite competition by concentrating power. Cooperation returned, but at the cost of the republican system.

Medieval Europe: Fragmented Elites and Persistent Conflict

European feudalism represents a long period of elite fragmentation. Nobility competed for land, titles, and power. No central authority could coordinate elite cooperation across regions. The result was centuries of persistent low-intensity conflict.

The transition to modern state systems (17th-18th centuries) involved building institutions that could coordinate elite cooperation at larger scale: professional bureaucracies, standing armies, fiscal systems. Where these succeeded (France, England), states strengthened. Where they failed (Holy Roman Empire, Poland), states collapsed.

United States: New Deal Cooperation to Contemporary Competition

Post-WWII America showed remarkable elite cooperation. Business, labor, and government cooperated on New Deal/Great Society institutions. Elite numbers were constrained. Long-term investment in infrastructure, education, science was norm. State capacity was high.

By the 1980s-1990s, this cooperation was fraying. Elite numbers exploding (credential inflation, wealth concentration). Neoliberal ideology justifying short-termism and disinvestment from public goods. Factionalism intensifying (Gingrich revolution, Tea Party, MAGA, progressive left). Norms breaking down (government shutdowns, judicial blocks, election contestation).

The contemporary United States represents severe elite competition. Governance is paralyzed. Public investment has collapsed relative to need. Norms are strategic tools. The state can't coordinate response to major challenges (pandemic, climate, infrastructure decay).

Counter-Elites: Competition's Sharpest Edge

The most destabilizing form of elite competition is counter-elite formation: elites who can't access power through normal channels building alternative power bases by challenging incumbent elites.

The Counter-Elite Strategy

Counter-elites can't win on incumbents' terms, so they change the game:

- Delegitimize existing institutions: "The system is rigged," "The establishment is corrupt," "The elite are out of touch"

- Mobilize popular discontent: Frame themselves as champions of the people against corrupt elites

- Offer radical alternatives: Promise systemic transformation that would create new elite positions

- Build parallel institutions: Media ecosystems, funding networks, organizational capacity outside incumbent control

This strategy is effective because elite overproduction creates genuine grievances. Credentialed people blocked from elite positions feel betrayed. They're receptive to narratives about rigged systems. Counter-elites provide those narratives and leadership.

Why Counter-Elites Are Destabilizing

Counter-elites accelerate societal fragmentation:

- They weaponize narrative fragmentation, creating incompatible stories about reality

- They legitimize norm-breaking ("the system is corrupt, we need revolutionary change")

- They polarize politics into existential conflict rather than normal competition

- They make elite cooperation impossible (incumbents and counter-elites can't compromise)

The presence of powerful counter-elite movements is the clearest signal that a society has entered the disintegrative crisis phase. Not protest—all societies have protest. But elite-led movements promising systemic transformation. That's the signature of structural crisis.

Elite Dynamics and Meaning Production

Elites don't just coordinate institutions. They produce and propagate meaning through cultural authority.

Universities, media, arts, religion—these meaning-making institutions are elite-run. The narratives, values, and aesthetics they produce shape how the broader population understands reality. When elites cooperate, these institutions produce relatively coherent shared meaning. When elites compete, they produce fragmented, competing meanings.

Integration: Shared Meaning Production

During elite cooperation, meaning-making institutions converge. Not through conspiracy, but through:

- Shared educational background (elite universities)

- Overlapping social networks (elite circles)

- Common incentives (elite career paths)

- Institutional norms (professional standards)

This produces culture that, while diverse, operates within shared frameworks. Disagreement occurs within boundaries. The culture feels cohesive even as it evolves.

Disintegration: Weaponized Meaning

During elite competition, meaning-making becomes weapon. Competing elite factions capture institutions and use them for factional advantage:

- Universities become "liberal indoctrination" vs. "training critical thinking"

- Media becomes "fake news propaganda" vs. "truth-telling resistance"

- Arts become "woke" vs. "subversive"

- Religion becomes "oppressive tradition" vs. "moral foundation"

This isn't about which side is right. It's about elite competition transforming institutions from shared resources into factional weapons. The meaning they produce fragments along factional lines, accelerating narrative fragmentation.

Can Elite Cooperation Be Restored?

The hard question: if elite competition is driving disintegration, can cooperation be restored without going through full crisis and reset?

The Structural Problem

Elite overproduction creates a prisoners' dilemma. Any individual elite who cooperates while others compete loses. Defection (competition) is rational even though universal defection (everyone competing) produces worse outcomes than universal cooperation.

Breaking this requires either:

- Reducing elite numbers (through redistribution, downward mobility, or crisis-driven culling)

- Expanding elite positions (through economic growth, new industries, or institutional creation)

- Changing payoff structures (making cooperation more valuable than competition through institutional design)

- External forcing (threat that makes cooperation necessary for survival)

None of these are easy in the disintegrative phase. Elite numbers are high and resistant to reduction. Economic growth is difficult when state capacity is degraded. Institutional design requires elite cooperation to implement. External threats are unpredictable.

Historical Precedent

Elite cooperation is usually restored through:

- Crisis and culling: Civil war, revolution, or economic collapse reduces elite numbers violently

- Generational replacement: Competing elites age out, new generation builds new cooperation

- External shock: War or catastrophe forces cooperation

- Radical restructuring: New political/economic system creates new elite positions (American Revolution, French Revolution, post-WWII settlement)

Notice the pattern: restoration typically requires trauma. The system has to break before it can rebuild cooperation.

The Optimistic Case

The optimistic scenario is that contemporary elites recognize the structural problem and choose to cooperate before full crisis. This would require:

- Progressive taxation reducing wealth concentration

- Credentialing reform reducing elite aspirant numbers

- Institutional reform expanding meaningful positions

- Cultural shift valorizing cooperation over competition

This is possible. But it requires elites to act against their short-term interests during precisely the period when competition makes short-term thinking dominant. The historical record is not encouraging.

This is Part 7 of the Cliodynamics series, exploring Peter Turchin's mathematical history through AToM coherence geometry.

Previous: Narrative Fragmentation

Next: What History Teaches About Recovery

Further Reading

- Turchin, P. (2016). Ages of Discord: A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History. Beresta Books.

- Mills, C. Wright (1956). The Power Elite. Oxford University Press.

- Scheidel, W. (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press.

- Tilly, C. (1992). Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1992. Wiley-Blackwell.

Comments ()