Entropy: The Second Law's Enforcer

In 1865, Rudolf Clausius needed a name for his new quantity. He'd discovered something fundamental—a measure of how much thermal energy was unavailable for useful work. He chose "entropy," from the Greek entropia, meaning transformation.

The name stuck. The concept conquered physics. Entropy became the bookkeeper of the Second Law, the quantity that tracks the universe's one-way slide toward equilibrium. And it turned out to be far stranger and more powerful than Clausius imagined.

What Entropy Actually Is

Entropy has multiple definitions, each correct, each revealing a different facet:

Clausius (1865): Entropy is the integral of heat divided by temperature. dS = dQ/T for reversible processes. This was the original—a thermodynamic definition with no mention of atoms.

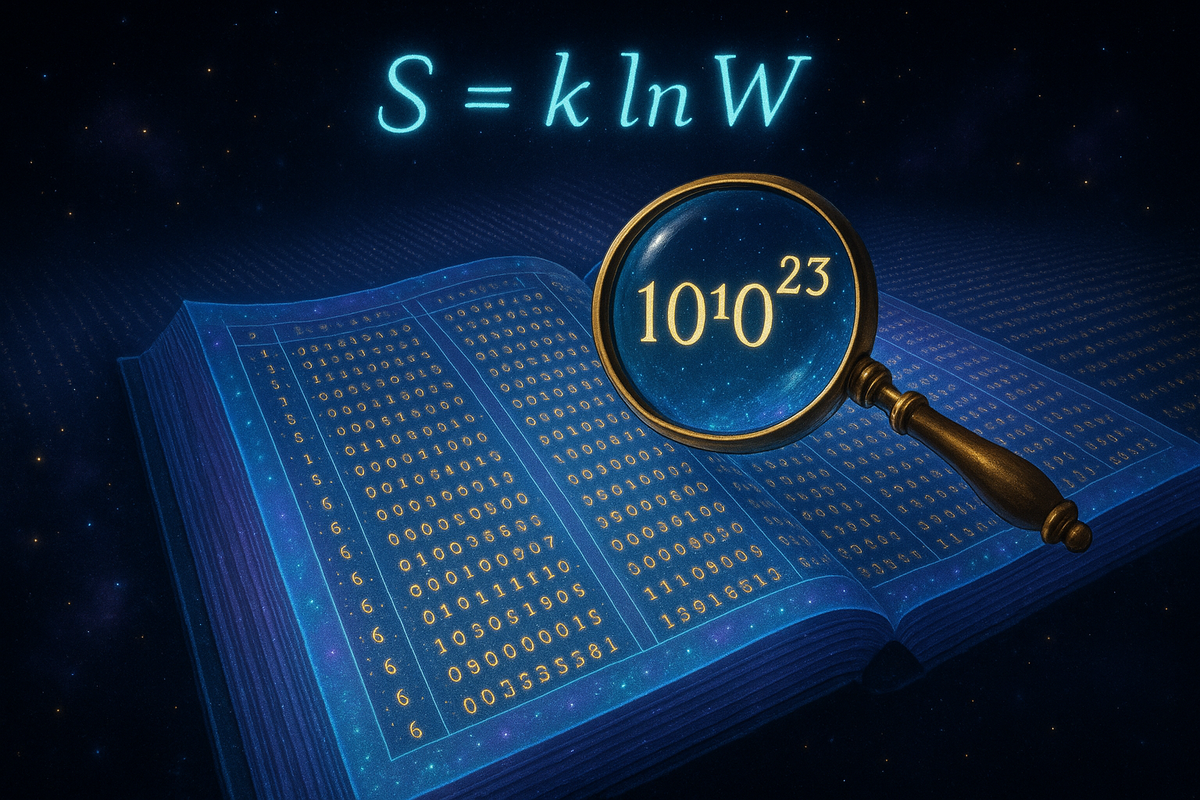

Boltzmann (1877): S = k ln W. Entropy is the logarithm of the number of microstates. This statistical definition connects entropy to probability and counting.

Gibbs (1878): S = -k Σ pᵢ ln pᵢ. Entropy is the expectation value of surprise. This generalizes Boltzmann's formula to non-equilibrium situations.

Shannon (1948): H = -Σ pᵢ log pᵢ. Information entropy measures uncertainty in a message. Same mathematics as Gibbs, different domain.

Modern synthesis: Entropy measures how many microscopic arrangements are consistent with a macroscopic description. It quantifies our ignorance of the exact state while knowing the bulk properties.

The pebble: Entropy has many faces, but one core meaning: how spread out is possibility? How many ways could the parts be arranged while looking the same from outside?

Why Entropy Increases

The Second Law says entropy increases (or stays constant) in isolated systems. But why? What forces entropy upward?

The answer is: nothing. There's no entropy force. Entropy increases because there are more ways to be high-entropy than low-entropy.

Consider a box of gas with a partition. Left side: all the molecules. Right side: vacuum. Remove the partition. The gas spreads out. Why?

Not because molecules "want" to spread. They just bounce randomly. But there are vastly more arrangements where molecules occupy both sides than arrangements where they all stay on one side. As molecules bounce, the system wanders through microstates. It ends up in high-entropy arrangements simply because there are more of them.

The pebble: Entropy increase isn't driven by a force. It's driven by math. There are more ways to be disordered, so random wandering finds disorder.

The Clausius Definition: Heat and Temperature

Clausius defined entropy change as: dS = dQ_rev / T

Where: - dS is the entropy change - dQ_rev is heat transferred reversibly - T is absolute temperature

This means: 1. Adding heat increases entropy (dQ > 0 → dS > 0) 2. The same heat matters more at low temperature (dividing by T amplifies the effect) 3. Reversible processes have zero net entropy change for the universe

Why divide by temperature? Because high-temperature heat is "worth less" entropically. A joule at 1000 K spreads over many existing microstates. A joule at 100 K is a bigger deal—it represents a larger relative addition.

The Boltzmann Definition: Counting Microstates

Boltzmann's formula S = k ln W defines entropy as a count of microstates.

W is the number of microscopic arrangements consistent with the macroscopic state. For a gas, W depends on how molecules can distribute across positions and velocities while maintaining the same pressure and temperature.

The logarithm has important properties: - Makes entropy additive (combine two systems, add their entropies) - Grows slowly (W can be astronomically huge, but S stays manageable) - Connects to probability (probabilities multiply, logs add)

For perspective: a mole of gas has W ≈ 10^(10²³). That's a number so large that scientific notation fails. But its logarithm is merely 10²³ (times the Boltzmann constant). The log tames infinity.

The pebble: Boltzmann's entropy is counting—but at scales so large that counting itself breaks. The logarithm is the ladder that lets us climb the tower of astronomical numbers.

Entropy and Information

Claude Shannon invented information theory in 1948. He needed a measure of how much information a message contains. He landed on: H = -Σ pᵢ log pᵢ

This is Gibbs' entropy formula, renamed. Shannon called it "entropy" deliberately—he'd consulted John von Neumann, who reportedly told him to use the term because "nobody really knows what entropy is, so in a debate you will always have the advantage."

But the connection is deeper than a borrowed name. Information entropy and thermodynamic entropy are the same quantity in different contexts.

When you don't know which microstate a system is in, you lack information. High entropy = high uncertainty = more bits needed to specify the state. Thermodynamic entropy is informational entropy about molecular arrangements.

The pebble: Entropy measures ignorance. The Second Law says: you can't become less ignorant about the universe's microstate without doing work.

Landauer's Principle: Information Is Physical

In 1961, Rolf Landauer proved something profound: erasing one bit of information requires dissipating at least kT ln 2 joules of energy.

This connects information to thermodynamics with a physical equation. Information isn't abstract—it's embodied in physical systems, and manipulating it costs energy.

Why does erasure cost energy? Because erasing a bit reduces the number of possible states (from two to one). That's an entropy decrease. To stay consistent with the Second Law, entropy must increase elsewhere—as heat dissipated into the environment.

Your computer gets hot not just because of resistance and friction, but because computation involves erasure, and erasure requires entropy export.

The pebble: Every time you delete a file, the universe gets imperceptibly warmer. Information is physical, and the Second Law collects its tax.

Entropy in Practice

Why Hot Coffee Cools

Your coffee has thermal energy. The air is cooler. Heat flows from coffee to air. Why?

There are more microstates where thermal energy is spread between coffee and air than concentrated in the coffee. The system evolves toward more microstates. Entropy increases. The coffee cools.

Why Ice Melts

At 0°C, ice and water have the same free energy, but liquid water has higher entropy (more molecular arrangements). Above 0°C, the entropy term dominates, favoring melting. Below 0°C, the energy term dominates, favoring freezing.

Why Perfume Spreads

Open a perfume bottle, and the scent fills the room. Not because perfume molecules are pushed outward, but because there are more arrangements where molecules spread than where they stay bottled. Random motion finds spread.

Why Rooms Get Messy

There are many disordered arrangements of objects in a room and few ordered ones. Without effort (energy input), systems drift toward high-entropy states. Cleaning requires work—you're locally decreasing entropy by exporting it elsewhere.

Entropy and Time

The Second Law creates the arrow of time. Entropy increase defines "forward."

Play a video backward. If entropy decreases in the reversed video, you know it's backward. Eggs unscrambling, smoke compressing into a candle, ice cubes forming from warm water—these are entropy-decreasing processes that never occur spontaneously.

But why was the past lower entropy? This is the Past Hypothesis—the assumption that the Big Bang was a low-entropy state. From that special beginning, entropy has been increasing ever since.

Why was the Big Bang low-entropy? We don't know. It's one of the deepest puzzles in physics.

Entropy and Life

Living systems are low-entropy structures: organized, improbable, far from equilibrium. How do they exist without violating the Second Law?

By exporting entropy. Every living thing is an entropy pump: - Take in low-entropy matter (food, sunlight) - Organize it into structure and function - Export high-entropy waste (heat, CO₂, excrement)

The total entropy—organism plus environment—always increases. Life surfs the entropy gradient from the sun (low-entropy photons) to deep space (high-entropy infrared radiation).

The pebble: Life is a temporary eddy in entropy's river. We persist by making the universe more disordered faster than we order ourselves.

Common Misconceptions

"Entropy is disorder"

Misleading. A shuffled deck isn't more "disordered" than a sorted one in any meaningful physical sense. Entropy is about the number of equivalent microstates, not human judgments of tidiness.

"Entropy always increases"

Only in isolated systems. Open systems can decrease entropy by exporting it. Earth's biosphere decreases local entropy by radiating heat to space.

"The Second Law proves evolution impossible"

Wrong. Evolution creates local order by exporting entropy through metabolism. Organisms are open systems, not isolated ones.

"We can reverse entropy"

Locally, yes—that's what refrigerators do. Globally, no. Every local decrease requires a greater increase elsewhere.

Entropy and the Fate of the Universe

If entropy always increases, where does it end?

Heat death: maximum entropy, uniform temperature, no gradients, no change. The universe would still exist but nothing would happen. All energy equally distributed, no work possible, no life.

This is trillions of years away. But it's where the Second Law points.

The Deepest Insight

Entropy connects: - Thermodynamics (heat engines, phase transitions) - Statistical mechanics (counting microstates) - Information theory (bits and uncertainty) - Cosmology (the arrow of time) - Biology (life as dissipative structure) - Computation (the physics of information processing)

No other concept spans so many domains. Entropy is the thread running through physics, linking the very large to the very small, the abstract to the concrete.

The pebble: Entropy is physics' most universal concept—more universal even than energy, because entropy has a direction that energy lacks.

Further Reading

- Ben-Naim, A. (2008). A Farewell to Entropy. World Scientific. - Carroll, S. (2010). From Eternity to Here. Dutton. - Penrose, R. (2004). The Road to Reality. Knopf. (Chapters 27-28)

This is Part 6 of the Laws of Thermodynamics series. Next: "Maxwell's Demon: The Thought Experiment That Wouldn't Die"

Comments ()