Euler's Formula: The Most Beautiful Equation in Mathematics

In 1988, a physicist named Richard Feynman wrote in his private notebook: "This is the most remarkable formula in mathematics."

He was talking about a single line, discovered by Leonhard Euler in 1748:

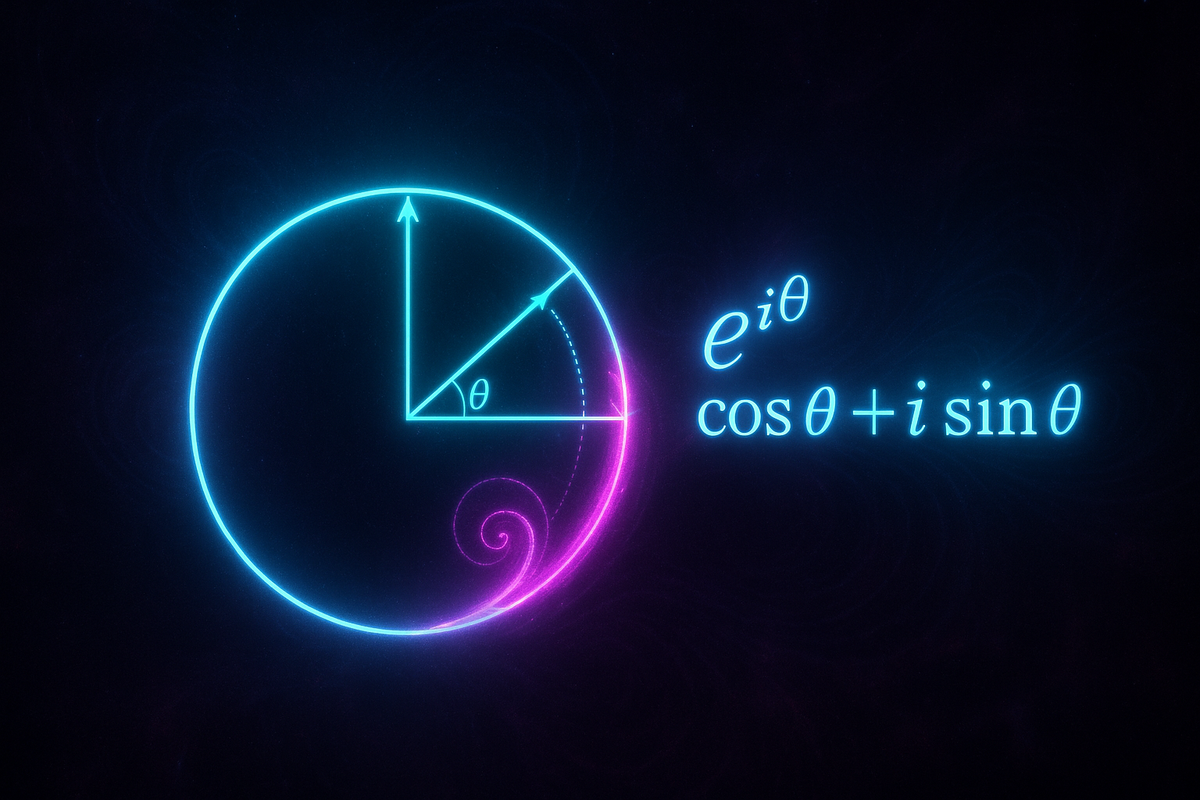

e^(iθ) = cos θ + i sin θ

On the left: an exponential function raised to an imaginary power. On the right: two trigonometric functions—one tracking horizontal position, one tracking vertical—added together with an imaginary twist.

What could these possibly have to do with each other?

Here's the punchline, and it's a weird one: exponentials and rotation are the same thing. Not metaphorically. Not "kind of similar." Mathematically identical. When you raise e to an imaginary power, you spin.

The Setup: What Are These Symbols?

Let's make sure we're speaking the same language.

e is the natural exponential base, roughly 2.71828. It's the number that calculus prefers—the one where d/dx(e^x) = e^x. The function that is its own rate of change.

i is the imaginary unit, defined by i² = -1. It's not "imaginary" in the sense of being fake. It's perpendicular to the real number line. If real numbers stretch left and right, i points up.

θ (theta) is just an angle, measured in radians.

cos θ and sin θ are the horizontal and vertical coordinates of a point on a unit circle at angle θ.

None of these seem related. Exponential growth? Imaginary numbers? Circles? Three completely different chapters in a math textbook.

And yet.

The Weird Connection

Here's what happens when you compute e^(iθ) properly.

You know how e^x can be written as an infinite series:

e^x = 1 + x + x²/2! + x³/3! + x⁴/4! + ...

Now substitute x = iθ:

e^(iθ) = 1 + (iθ) + (iθ)²/2! + (iθ)³/3! + (iθ)⁴/4! + ...

Here's where it gets interesting. Remember that i² = -1. So:

- i¹ = i

- i² = -1

- i³ = -i

- i⁴ = 1

- i⁵ = i (and it cycles)

When you expand that series and sort the real and imaginary terms:

e^(iθ) = (1 - θ²/2! + θ⁴/4! - ...) + i(θ - θ³/3! + θ⁵/5! - ...)

That first parenthesis is the Taylor series for cos θ. The second is the Taylor series for sin θ.

So: e^(iθ) = cos θ + i sin θ

The proof is mechanical. The result is not. Something deep is happening here.

What This Actually Means

Here's the mind-bending part: e^(iθ) traces a circle.

As θ increases from 0 to 2π, the value of e^(iθ) walks around the unit circle in the complex plane. At θ = 0, you're at (1, 0). At θ = π/2, you're at (0, 1). At θ = π, you're at (-1, 0). At θ = 2π, you're back at (1, 0).

Exponentials grow. Or so you thought.

When the exponent is imaginary, the function doesn't grow—it rotates. The magnitude stays 1. Only the angle changes.

This means multiplication by e^(iθ) is rotation by angle θ.

Want to rotate a point 90 degrees counterclockwise? Multiply by e^(iπ/2). Want to rotate 180 degrees? Multiply by e^(iπ).

Rotation has been hiding inside exponentiation this whole time.

Why Does Growth Become Rotation?

The intuition is this: exponential growth is what happens when the rate of change is proportional to the current value. You have $100, it grows 5%, now you have $105, which grows 5%, and so on.

But what if that growth is perpendicular to your current position?

On the real line, e^x grows by pushing outward—the derivative points in the same direction as the value.

On the complex plane, e^(ix) grows by pushing sideways—the derivative is perpendicular to the value. (Because multiplying by i rotates by 90 degrees.)

If your velocity is always perpendicular to your position, you don't spiral outward. You orbit. You trace a circle.

The exponential function on imaginary numbers doesn't explode. It spins.

The Engineering Superpower

Euler's formula isn't just beautiful—it's weaponized across physics and engineering.

Electrical engineers describe alternating current using e^(iωt) instead of sin(ωt). Why? Because exponentials are easier to differentiate, integrate, and manipulate algebraically. At the end, you just take the real part.

Quantum mechanics uses complex exponentials everywhere. The wave function evolves as e^(-iHt/ℏ). Probability amplitudes are complex numbers. Interference patterns arise when these rotating phases add up.

Signal processing turns sounds and images into sums of complex exponentials (the Fourier transform). Every filter, every compression algorithm, every synthesizer is doing algebra in Euler's playground.

The reason? Sines and cosines are awkward. They have two terms each. Addition formulas are painful. But e^(iθ) is a single object that multiplies cleanly: e^(iα) · e^(iβ) = e^(i(α+β)).

Angles add when exponentials multiply. That's the whole trick.

The Philosophical Punchline

Here's what gets me about Euler's formula.

Mathematics didn't have to work this way. There's no obvious reason why the number that defines continuous growth (e), the number that defines impossibility-made-possible (i), and the functions that describe circles (sin, cos) should all be the same thing viewed from different angles.

But they are.

Euler's formula reveals that these aren't separate topics. They're different faces of a single underlying structure. The complex exponential is more fundamental than any of its projections.

It's like discovering that ice and steam are both water. Obvious in hindsight. Deeply weird before you see it.

This is what pure mathematics feels like when it's working. The universe is not a collection of separate phenomena. It's a unified system that humans keep rediscovering in pieces, and occasionally we find an equation that shows two pieces were always one.

e^(iπ) + 1 = 0 isn't just elegant notation. It's a message that we're on the right track.

Further Reading

- Nahin, P. (2006). Dr. Euler's Fabulous Formula. Princeton University Press.

- Needham, T. (1997). Visual Complex Analysis. Oxford University Press.

- 3Blue1Brown. "Euler's Formula and Introductory Group Theory." YouTube—an exceptional visual explanation.

- Feynman, R. (1977). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. I, Chapter 22.

This is Part 5 of the Complex Numbers series, exploring mathematics beyond the real line. Next: "Euler's Identity: When e, π, i, 1, and 0 Meet."

Part 5 of the Complex Numbers series.

Previous: Polar Form: Complex Numbers as Rotation and Scaling Next: Euler's Identity: When e π i 1 and 0 Meet

Comments ()