Evaluating Coherence Communities: Healthy vs Harmful Groups

Evaluating Coherence Communities: Healthy vs Harmful Groups

Series: Gene-Culture Coevolution | Part: 8 of 9

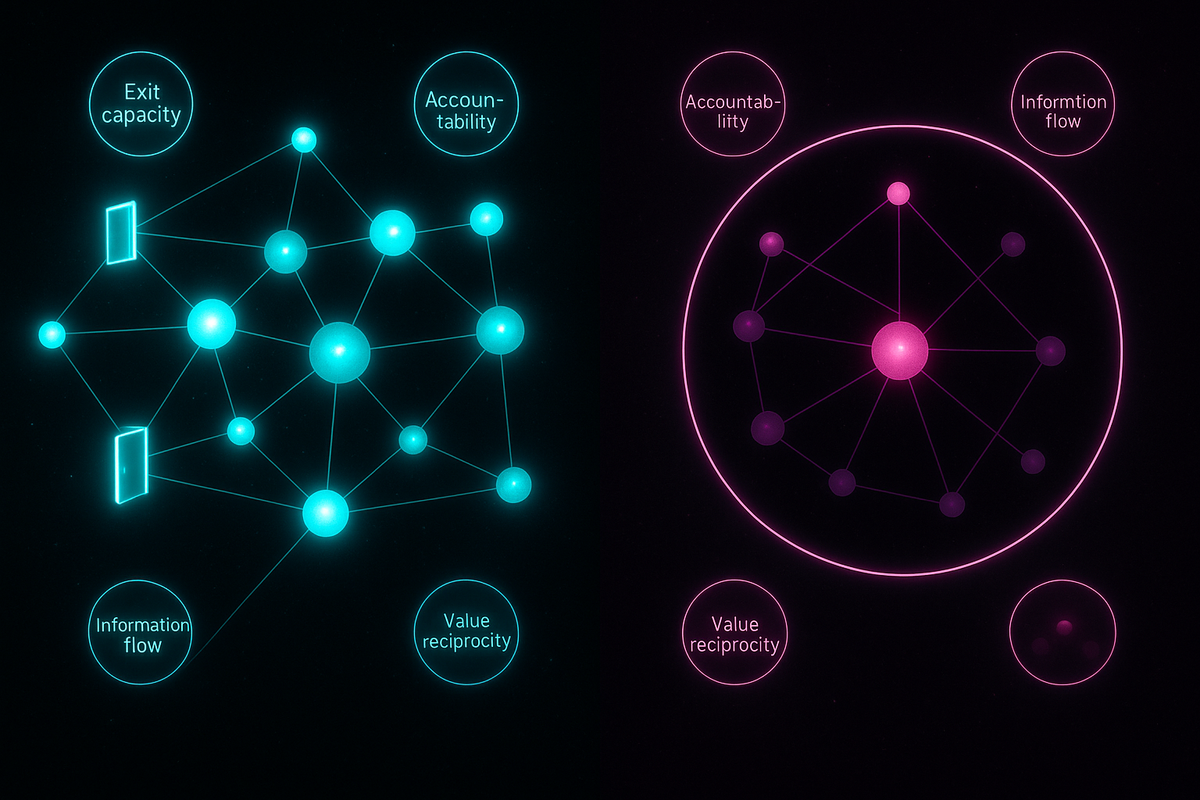

Not all coherence communities are created equal. Some genuinely serve member flourishing—providing meaning, connection, growth, and support. Others exploit coherence hunger—extracting resources, limiting autonomy, and damaging members while providing only the illusion of integration.

The line between healthy and harmful isn't always clear. Groups exist on a spectrum. And the same mechanisms that make communities functional—costly commitment, strong boundaries, charismatic leadership, intense practices—can become pathological under the wrong conditions.

This article provides a framework for evaluating coherence communities—whether religious movements, political organizations, fitness cultures, online tribes, or any group that offers identity and meaning in exchange for commitment.

The goal isn't to avoid community. Humans need coherence communities to function. The goal is discernment: recognizing when a group genuinely serves coherence vs. when it exploits coherence hunger for other ends.

The Core Question: Does the Group Serve Members or Itself?

Healthy communities exist to serve member flourishing. The group's purpose is to help individuals develop, connect, and thrive. Success is measured by member wellbeing.

Harmful communities exist to serve the group (or its leaders). Members exist to sustain the organization, enrich leadership, or fulfill the group's mission. Individual wellbeing becomes secondary to organizational preservation.

This difference shows up in whose needs take priority when there's conflict between individual and institutional interests.

Healthy pattern: "Your mental health is deteriorating—you should take a break from intensive practice."

Harmful pattern: "Your doubts are selfish. The community needs your commitment. Taking a break is abandoning the mission."

The first prioritizes member wellbeing. The second prioritizes organizational preservation. This distinction appears in dozens of micro-interactions and reveals the group's fundamental orientation.

Exit Capacity: The Ultimate Test

Alexandra Stein, researcher on authoritarian groups, proposes a simple heuristic: Can you leave?

Not legally—most groups allow formal exit. But practically:

- Can you express doubt without social consequences?

- Can you reduce participation without losing relationships?

- Can you leave without financial ruin?

- Can you exit without identity collapse?

- Can you maintain relationships with members after leaving?

Healthy communities make exit possible, if costly. You'll lose community benefits, but you won't lose your life, livelihood, or entire social network.

Harmful communities make exit prohibitively expensive. Leaving means losing everything—family, friends, income, identity, meaning. The costs are designed to trap members even when the group is damaging them.

Mechanisms That Restrict Exit

Isolation: Cutting ties with non-members ("worldly people," "toxic influences," "normies"). If the only people you know are in the group, leaving means total social isolation.

Financial dependence: Requiring members to donate most income, work for the organization, or live communally. Leaving without savings or job skills makes exit nearly impossible.

Information control: Limiting access to outside perspectives, critical information, or former members. If you only hear the group's narrative, you can't evaluate alternatives.

Thought-stopping techniques: Teaching members to dismiss doubt as "ego," "satanic influence," or "lack of faith." This prevents internal reflection that might lead to exit.

Shunning policies: Requiring members to cut contact with anyone who leaves. This makes exit equivalent to social death and prevents current members from hearing exit narratives.

When these mechanisms are strong, exit capacity approaches zero. Members stay not because the group serves them, but because leaving is too costly. This is the defining feature of authoritarian or cult-like groups.

Warning Signs: Red Flags in Community Dynamics

1. Charismatic Authority Without Accountability

Leadership claiming special access to truth, divine authority, or unique insight—combined with no accountability mechanisms—is dangerous.

Healthy: Leaders are fallible, subject to feedback, and replaceable. Disagreement is permitted. Criticism is addressed, not punished.

Harmful: Leader is infallible, beyond criticism, irreplaceable. Questioning leadership is heresy. Criticism triggers punishment.

2. Information Control

Limiting members' access to outside perspectives, critical information, or former member accounts.

Healthy: Members encouraged to read widely, engage with critics, and form independent judgments.

Harmful: Outside information labeled as deception, contamination, or spiritual danger. Critical sources prohibited or pre-interpreted to dismiss them.

3. Binary Thinking

Dividing the world into absolute categories: enlightened vs. asleep, saved vs. damned, red-pilled vs. blue-pilled.

Healthy: Recognizing complexity, ambiguity, and degrees of understanding. Room for nuance and partial agreement.

Harmful: No middle ground. You're either fully in or you're the enemy. Nuance is weakness or confusion.

4. Escalating Commitment

Requirements that increase over time without proportional benefit.

Healthy: Commitment scales with value received. Members can participate at varying intensities. Boundaries respected.

Harmful: Constant pressure for more—more time, money, devotion, sacrifice. Never enough. Boundaries are "resistance" or "ego."

5. Love Bombing and Conditional Affection

Initial overwhelming affection and acceptance—followed by withdrawal when members don't conform.

Healthy: Consistent warmth that doesn't depend on perfect compliance. Relationships survive disagreement.

Harmful: Affection contingent on conformity. Withdrawal of warmth used as punishment for doubt or deviation.

6. Manufactured Crisis

Creating constant urgency, external threat, or impending catastrophe to justify extreme demands.

Healthy: Realistic assessment of challenges. Responses proportional to actual threat.

Harmful: Everything is an emergency. Outside world is imminently dangerous. Only total commitment can save you/us/the world.

7. Exploitation

Leaders enriching themselves while members sacrifice. Financial opacity. Resource extraction without reciprocal value.

Healthy: Transparent finances. Leaders' lifestyles commensurate with members'. Value flows reciprocally.

Harmful: Leaders live lavishly while members struggle. Donations go to undisclosed purposes. Questioning finances is prohibited.

Healthy Coherence: What Functional Communities Look Like

Functional communities provide genuine coherence without exploitation. They're characterized by:

Psychological Safety

You can express doubt, ask questions, disagree, and make mistakes without fear of ejection or punishment. Relationships survive conflict.

Developmental Arc

The community helps members grow. There's progression—you develop skills, understanding, relationships, autonomy. You're encouraged to eventually reduce dependence on the group.

Value Reciprocity

Members receive proportional value for their investment. Time, money, and energy spent translate to genuine skill development, meaningful relationships, or tangible benefits.

External Relationships Maintained

The community encourages (or at least permits) relationships with family, friends, and others outside the group. You're not forced to choose.

Leader Humility

Leaders acknowledge limitations, welcome feedback, and create accountability structures. Power is distributed or checked.

Flexible Commitment

You can participate at varying intensities. Reducing participation is okay. Life circumstances change, and the community adapts.

Reality-Testing

The group's claims are falsifiable and engage with evidence. Disagreement is productive. Outside perspectives are considered seriously.

The Nuance: Costs vs. Control

Here's the complexity: Costly commitment is necessary for coherence, but excessive control is harmful.

Functional communities require investment. Learning a skill takes time. Building relationships requires vulnerability. Transformation requires challenging yourself. These costs are legitimate and productive.

The question is whether the costs are:

Proportional to benefits: Does the value you receive justify the investment?

Freely chosen: Can you assess costs and decide whether to pay them?

Transparent: Do you understand what you're committing to?

Reversible: Can you change your mind and exit if it's not working?

If yes to these, costly commitment is healthy. If no—if costs are hidden, escalating, non-consensual, or irreversible—it's control.

Practices like fasting, meditation retreats, or intensive training are costly. But they can be chosen, understood, and stopped. That's healthy cost.

Cutting off family, donating your savings, or renouncing legal rights are costly. If they're presented as mandatory, irreversible, or as tests of faith, that's harmful control.

Practical Discernment

When evaluating a community (or your current involvement in one):

Can I leave? Practically, not just legally. What would I lose?

Am I growing? Developing skills, autonomy, relationships, understanding? Or just more dependent?

Can I question? Safely express doubt, disagree, or criticize without consequences?

Are my boundaries respected? Or constantly pushed, dismissed, or pathologized?

Do leaders model what they teach? Or are there different rules for them?

Is information open? Can I access critical perspectives and former member accounts?

Do I have external relationships? Or has the group become my entire world?

Is the cost proportional? Am I getting value commensurate with investment?

If the answers are mostly healthy, the community is probably functional. If the answers are concerning, trust your instinct. Coherence hunger is real, but so is exploitation. Not every group that offers meaning deserves your trust.

The Coherence-Exploitation Spectrum

In AToM terms, healthy communities provide genuine coherence—integrated frameworks that help members navigate complexity, maintain relationships, and act effectively.

Harmful communities provide illusory coherence—surface integration that masks internal contradictions, restricts rather than expands possibility, and extracts value while claiming to provide it.

The difference isn't always obvious externally. Both create strong identity, demanding practices, and committed members. The difference is in directionality: Does engagement expand your autonomy and flourishing? Or contract it while making you more dependent?

Humans need coherence communities. We're built for them. But we're also vulnerable to groups that exploit that need. Discernment isn't cynicism. It's responsible engagement with the reality that not all offers of meaning are genuine—and your coherence is too important to hand over without evaluation.

This is Part 8 of the Gene-Culture Coevolution series, exploring how genes and culture evolve together to make humans uniquely human.

Previous: Digital Tribes: Gene-Culture Dynamics in Online Communities

Next: Synthesis: Humans as Coherence Community Generators

Further Reading

- Stein, A. (2017). Terror, Love and Brainwashing: Attachment in Cults and Totalitarian Systems. Routledge.

- Hassan, S. (2018). The Cult of Trump. Free Press.

- Lalich, J., & Tobias, M. (2006). Take Back Your Life: Recovering from Cults and Abusive Relationships. Bay Tree Publishing.

- West, L. J., & Singer, M. T. (1980). "Cults, quacks, and nonprofessional psychotherapies." In H. I. Kaplan, A. M. Freedman, & B. J. Sadock (Eds.), Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry (3rd ed., pp. 3245-3258). Williams & Wilkins.

Comments ()