Expected Value: The Long-Run Average

You're offered a bet. Roll a die: you win $10 on 6, lose $2 otherwise.

Should you take it?

Expected value answers this. It's the average outcome if you played the game infinitely many times. For this bet: (1/6)($10) + (5/6)(-$2) = $1.67 - $1.67 = $0.

The bet is fair. On average, you neither win nor lose.

Expected value is the single most important number in probability. It summarizes a random variable into one value that captures its center.

The Definition

For a discrete random variable X:

E[X] = Σ x · P(X = x)

Each possible value, weighted by its probability, summed.

Example: Fair die.

E[X] = 1(1/6) + 2(1/6) + 3(1/6) + 4(1/6) + 5(1/6) + 6(1/6) = (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6)/6 = 21/6 = 3.5

The expected value is 3.5—a number you can never actually roll. That's fine. Expected value isn't about any single outcome; it's about the long-run average.

For continuous random variables:

E[X] = ∫ x · f(x) dx

Same idea: each value weighted by its probability density, integrated.

Why "Expected"?

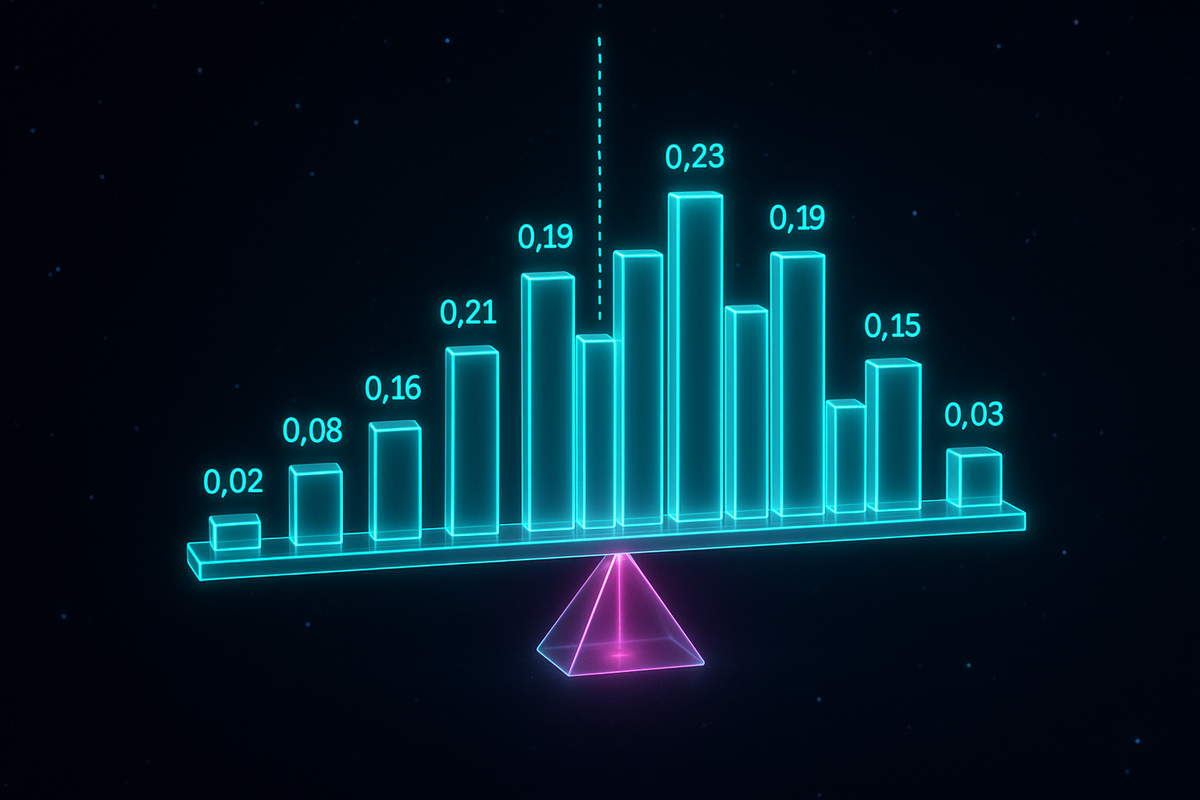

The name is somewhat misleading. E[X] isn't necessarily expected in the sense of "likely." It's the center of mass of the probability distribution.

If you had a physical bar shaped like the probability distribution, E[X] is where it balances.

For the die, it balances at 3.5. For a coin coded as 0/1, it balances at 0.5.

Properties of Expected Value

Linearity: The most important property.

E[aX + b] = aE[X] + b

E[X + Y] = E[X] + E[Y] — always true, even if X and Y are dependent!

Example: You roll two dice. What's E[sum]?

E[X + Y] = E[X] + E[Y] = 3.5 + 3.5 = 7

This is why 7 is the most common sum—it's the expected value.

Scaling: E[cX] = c · E[X]

Independence: If X and Y are independent, E[XY] = E[X] · E[Y]

(This fails for dependent variables.)

Expected Value of Functions

If Y = g(X), then:

E[Y] = E[g(X)] = Σ g(x) · P(X = x)

Example: X is a die roll. What's E[X²]?

E[X²] = 1²(1/6) + 2²(1/6) + 3²(1/6) + 4²(1/6) + 5²(1/6) + 6²(1/6) = (1 + 4 + 9 + 16 + 25 + 36)/6 = 91/6 ≈ 15.17

Note: E[X²] ≠ (E[X])² in general. Here, E[X]² = 3.5² = 12.25 ≠ 15.17.

Expected Value in Decisions

Expected value is the rational guide for repeated decisions.

Example: Insurance.

A $200 annual premium protects against a $10,000 loss that has 1% annual probability.

E[loss without insurance] = 0.01 × $10,000 = $100 E[cost with insurance] = $200

The insurance costs more than expected losses. But that's the point—you're paying for protection against catastrophic single events.

Expected value applies to the ensemble, not the individual case.

Example: Pascal's Wager.

Pascal argued: even if God's existence has low probability, infinite reward (heaven) times any positive probability equals infinite expected value. So you should believe.

The argument has issues, but it introduced expected value reasoning to philosophy.

The Law of Large Numbers (Preview)

Why should you care about expected value if single outcomes vary?

Because of this remarkable fact: the average of many independent random variables converges to the expected value.

If X₁, X₂, ..., Xₙ are independent with the same distribution:

(X₁ + X₂ + ... + Xₙ)/n → E[X] as n → ∞

This is the Law of Large Numbers. It's why casinos make predictable money, insurance works, and polls approximate population opinions.

The expected value isn't just theoretical—it's what actually happens in the long run.

Conditional Expected Value

E[X | Y = y] is the expected value of X when you know Y = y.

Example: You roll two dice. What's E[first die | sum = 9]?

When sum = 9, possible pairs are: (3,6), (4,5), (5,4), (6,3). First die values: 3, 4, 5, 6 — each equally likely. E[first die | sum = 9] = (3 + 4 + 5 + 6)/4 = 4.5

Compare to unconditional: E[first die] = 3.5.

Knowing the sum is 9 raises the expected first die from 3.5 to 4.5.

Law of Total Expectation:

E[X] = E[E[X | Y]]

The expected value of X equals the expected value of its conditional expected value, averaging over Y.

When Expected Value Doesn't Exist

Some distributions have undefined expected value.

The Cauchy Distribution:

f(x) = 1 / (π(1 + x²))

This is a valid PDF (integrates to 1), but E[X] = ∫ x f(x) dx diverges.

The distribution is so spread out that the average of many samples doesn't converge.

The St. Petersburg Paradox:

A game: flip coins until heads. Win $2ⁿ where n is the number of flips.

Expected value: Σ (1/2)ⁿ × 2ⁿ = Σ 1 = ∞

Infinite expected value! Should you pay any finite amount to play?

This paradox led to utility theory—expected utility, not expected money, should guide decisions.

Expected Value in Practice

Gambling: Every casino game has negative expected value for the player. That's not opinion—it's mathematics. The house edge is the expected loss per bet.

Investing: Expected return guides portfolio selection. But variance matters too—you care about risk as well as average return.

Testing: The expected number of tests to find a bug depends on your testing strategy and the distribution of bugs.

Queuing: Expected waiting time in a queue depends on arrival rate, service rate, and queue structure.

Common Expected Values

Bernoulli (coin flip): E[X] = p

Binomial (n trials, probability p): E[X] = np

Poisson (rate λ): E[X] = λ

Uniform (a to b): E[X] = (a + b)/2

Exponential (rate λ): E[X] = 1/λ

Normal (μ, σ²): E[X] = μ

The Essence

Expected value is the answer to "what happens on average?"

It compresses an entire probability distribution into a single number—the center. When that center is known, you know something fundamental about the random variable.

Combined with variance (measuring spread), expected value gives you the two most important summary statistics of any distribution.

This is Part 6 of the Probability series. Next: "Variance and Standard Deviation: Measuring Spread."

Part 6 of the Probability series.

Previous: Random Variables: Numbers That Depend on Chance Next: Variance and Standard Deviation: Measuring Spread

Comments ()