Exponential Decay: Half-Lives and Cooling

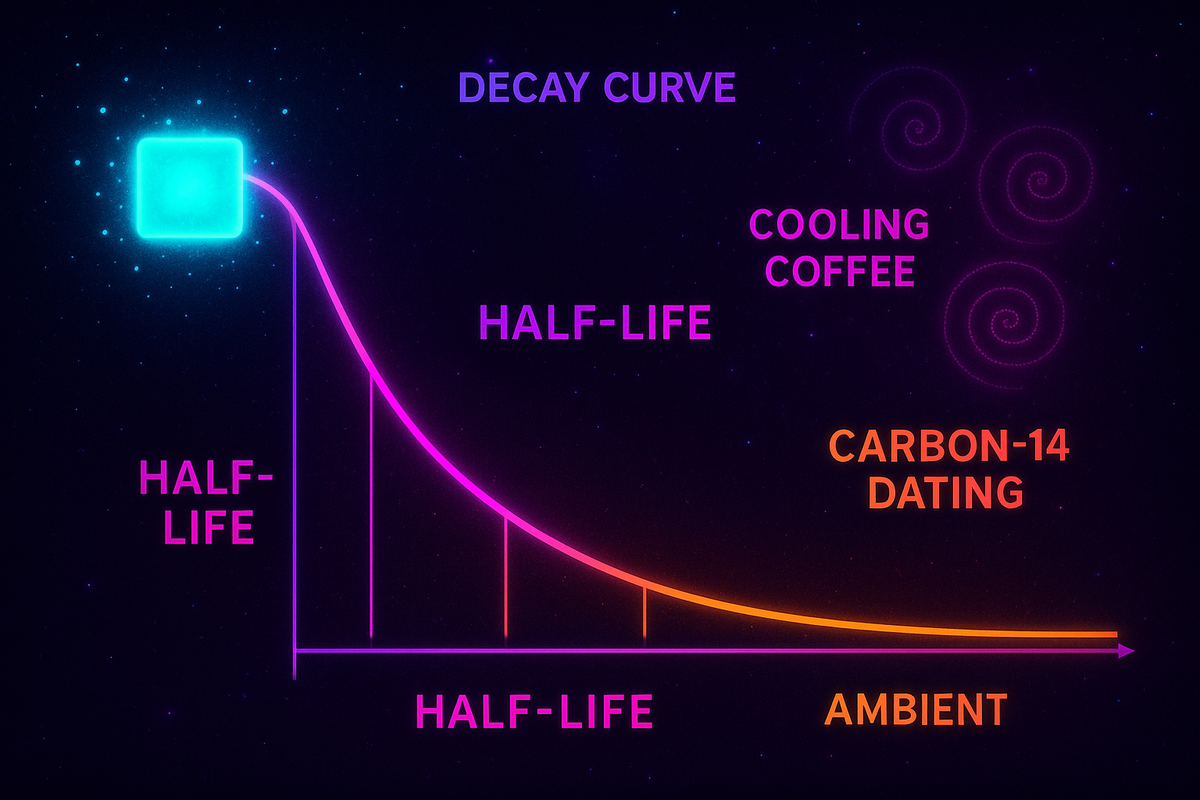

Exponential decay is exponential growth in reverse—shrinking that never quite finishes.

Radioactive atoms decay. Hot coffee cools. Medications clear from your bloodstream. All follow the same pattern: the more you have, the faster you lose it. But you never hit zero.

This is exponential decay. The quantity halves, and halves again, and halves again—forever approaching but never reaching zero.

The Defining Property

A quantity decays exponentially when its rate of decrease is proportional to its current size.

The more you have, the faster you lose it. But as you lose it, you have less, so you lose slower.

Mathematically: df/dt = -kf where k > 0.

Solution: f(t) = f₀ · e^(-kt)

Or in discrete form: f(n) = f₀ · bⁿ, where 0 < b < 1.

The key: each unit of time multiplies by a constant fraction. Not subtracts—multiplies by something less than 1.

Half-Life

Every exponential decay process has a half-life—the time it takes to reduce by half.

If f(t) = f₀ · (1/2)^(t/T½), then T½ is the half-life.

After one half-life: 100% → 50% After two half-lives: 50% → 25% After three half-lives: 25% → 12.5% After ten half-lives: 0.1% remains

The half-life formula:

T½ = ln(2)/k ≈ 0.693/k

Where k is the continuous decay rate.

This is the same formula as doubling time—the mathematics is symmetric.

Radioactive Decay

Radioactive isotopes decay with characteristic half-lives:

| Isotope | Half-life | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon-14 | 5,730 years | Dating organic material |

| Uranium-238 | 4.5 billion years | Dating rocks |

| Iodine-131 | 8 days | Medical imaging |

| Radon-222 | 3.8 days | Environmental hazard |

| Polonium-214 | 164 microseconds | Research |

A sample of Carbon-14:

- After 5,730 years: 50% remains

- After 11,460 years: 25% remains

- After 57,300 years (10 half-lives): 0.1% remains

Carbon dating works by measuring how much C-14 remains in organic material. The ratio tells you how many half-lives have passed.

Why Radioactive Decay Is Exponential

Each atom has a constant probability of decaying in any given time period. This probability doesn't depend on how long the atom has existed or how many other atoms are around.

If you have N atoms and each has probability p of decaying per second:

- Expected decays per second = pN

- This is proportional to N

Hence: dN/dt = -pN, giving exponential decay.

The randomness of individual decays averages to a smooth exponential curve when you have many atoms.

Newton's Law of Cooling

Hot objects cool exponentially toward ambient temperature:

T(t) = Tₐ + (T₀ - Tₐ)e^(-kt)

Where:

- T₀ is initial temperature

- Tₐ is ambient (surrounding) temperature

- k is the cooling constant

Example: Coffee starts at 90°C in a 20°C room.

T(t) = 20 + 70e^(-kt)

The coffee doesn't approach 0°C—it approaches 20°C. The decay is exponential in the difference from ambient.

If k = 0.1 per minute:

- At t = 0: 90°C

- At t = 10 min: 20 + 70e^(-1) ≈ 46°C

- At t = 20 min: 20 + 70e^(-2) ≈ 29°C

- At t = 30 min: 20 + 70e^(-3) ≈ 24°C

The coffee cools quickly at first (big temperature difference), then slowly as it approaches room temperature.

Drug Elimination

Medications leave your body exponentially. The half-life tells you how long the drug remains active.

Caffeine has a half-life of about 5 hours:

- 8 AM: Drink 200mg of caffeine

- 1 PM: 100mg remains

- 6 PM: 50mg remains

- 11 PM: 25mg remains

This is why coffee in the afternoon affects your sleep—25mg is still enough to cause problems.

Different drugs have wildly different half-lives:

- Aspirin: 15-20 minutes

- Ibuprofen: 2 hours

- Caffeine: 5 hours

- Alcohol: varies by body weight

Understanding half-lives explains dosing schedules. Take medication every half-life or so to maintain therapeutic levels.

The Mathematics

Discrete exponential decay: f(n) = f₀ · bⁿ, where 0 < b < 1

Example: 10% decay per period means b = 0.9: f(n) = 100 · (0.9)ⁿ

After 10 periods: 100 · (0.9)¹⁰ ≈ 35

Continuous exponential decay: f(t) = f₀ · e^(-kt)

Example: Continuous decay rate 10% per time unit: f(t) = 100 · e^(-0.1t)

After 10 time units: 100 · e^(-1) ≈ 37

Converting between half-life and decay rate: k = ln(2)/T½ ≈ 0.693/T½

If half-life is 5 hours, then k = 0.693/5 ≈ 0.139 per hour.

Never Reaching Zero

Exponential decay approaches zero asymptotically. Mathematically, it never gets there.

After n half-lives, the fraction remaining is (1/2)ⁿ:

- 10 half-lives: 1/1024 ≈ 0.1%

- 20 half-lives: 1/1,000,000 ≈ 0.0001%

- 30 half-lives: about 1 in a billion

In practice, "gone" means "below detection" or "too few atoms to matter." After 10 half-lives, most processes are effectively complete.

But mathematically, the curve never touches zero. This is the asymptotic nature of exponential decay.

Decay in Finance: Depreciation

Assets often depreciate exponentially. A car that loses 15% of its value each year:

V(t) = V₀ · (0.85)ᵗ

A $30,000 car:

- Year 1: $25,500

- Year 5: $13,300

- Year 10: $5,900

The biggest drops come early. Half the value is lost in the first 4-5 years.

This is why buying used can be economical: the steep part of the depreciation curve has already happened.

Exponential Decay vs. Linear Decay

Linear decay subtracts a constant amount. Exponential decay multiplies by a constant fraction.

Starting with 100, losing 10 per step (linear): 100 → 90 → 80 → 70 → 60 → 50 → 40 → 30 → 20 → 10 → 0

Starting with 100, keeping 90% per step (exponential): 100 → 90 → 81 → 73 → 66 → 59 → 53 → 48 → 43 → 39 → 35...

Linear decay hits zero in finite time. Exponential decay never hits zero.

Linear decay has constant absolute drops. Exponential decay has constant percentage drops.

The Forgetting Curve

Memory decay follows approximately exponential patterns. Without review, you forget:

- 50% within an hour

- 70% within 24 hours

- 90% within a week

This is Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve. Spaced repetition systems exploit this by timing reviews to catch memories before they decay below threshold.

The half-life of memory depends on the material and how well it was encoded. Well-learned material has longer half-lives.

Why Decay Matters

Exponential decay governs:

- How long contamination persists

- When drugs leave your system

- How quickly skills erode without practice

- How fast assets lose value

- How radiation hazards diminish

Understanding decay means understanding persistence—how long things last and why they last that long.

The key insight: early decay is fast, late decay is slow. Most of the action happens in the first few half-lives. After that, you're waiting for diminishing amounts to diminish further.

Part 3 of the Exponential Functions series.

Previous: Exponential Growth: When Doubling Never Stops Next: The Number e: The Base That Calculus Prefers

Comments ()