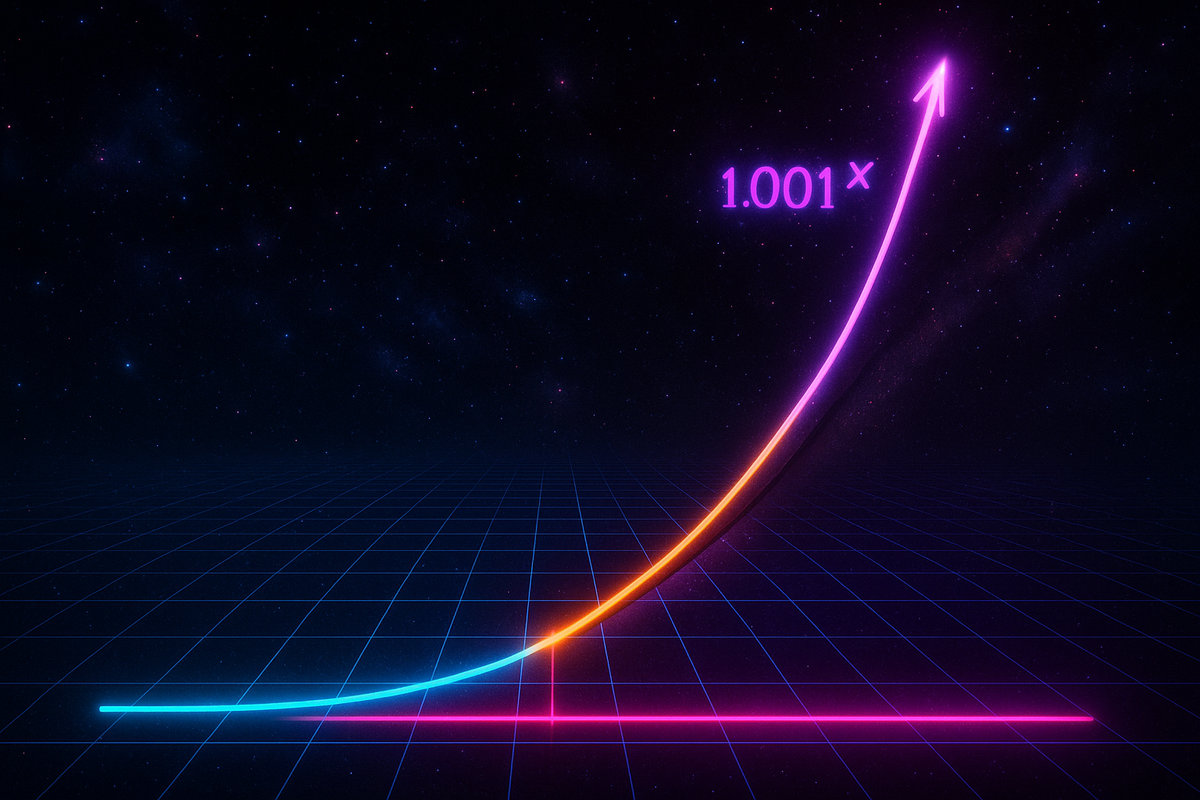

Exponential vs Polynomial Growth: Why Exponentials Always Win

Any exponential eventually beats any polynomial.

It doesn't matter how high the polynomial's degree. It doesn't matter how small the exponential's base (as long as it's greater than 1). Given enough time, exponential always wins.

x¹⁰⁰ looks massive. But 1.01ˣ eventually overtakes it. The turtle beats the hare—if the turtle is exponential and the hare is polynomial.

This is one of the most important facts in mathematics.

The Race

Let's race x² against 2ˣ:

| x | x² | 2ˣ | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2ˣ |

| 2 | 4 | 4 | Tie |

| 3 | 9 | 8 | x² |

| 4 | 16 | 16 | Tie |

| 5 | 25 | 32 | 2ˣ |

| 10 | 100 | 1,024 | 2ˣ |

| 20 | 400 | 1,048,576 | 2ˣ |

The polynomial leads early, but the exponential catches up and then explodes ahead.

Now try x¹⁰ against 2ˣ:

| x | x¹⁰ | 2ˣ | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 10¹⁰ | 2¹⁰ ≈ 10³ | x¹⁰ |

| 100 | 10²⁰ | 2¹⁰⁰ ≈ 10³⁰ | 2ˣ |

By x = 100, the exponential is already 10 billion times larger. The higher polynomial just delays the inevitable.

The Mathematical Statement

For any polynomial p(x) and any b > 1:

lim(x→∞) p(x) / bˣ = 0

No matter how high the degree, the polynomial becomes negligible compared to the exponential.

Equivalently:

lim(x→∞) bˣ / p(x) = ∞

The exponential grows infinitely larger than any polynomial.

Why This Happens

A polynomial of degree n grows like xⁿ for large x. Each step multiplies by approximately (1 + n/x), which approaches 1.

An exponential bˣ multiplies by exactly b each step—a constant greater than 1.

The polynomial's growth rate slows down. The exponential's never does.

More precisely:

d/dx(xⁿ) = nxⁿ⁻¹, which is order xⁿ⁻¹ (smaller than xⁿ)

d/dx(bˣ) = bˣ ln(b), which is order bˣ (same as the function)

The polynomial's derivative is a lower-degree polynomial. The exponential's derivative is another exponential of the same size. Exponentials sustain their rate of growth; polynomials can't.

L'Hôpital's Proof

To prove lim(x→∞) xⁿ/bˣ = 0, apply L'Hôpital's rule n times:

lim xⁿ/bˣ = lim nxⁿ⁻¹/(bˣ ln b) = lim n(n-1)xⁿ⁻²/(bˣ (ln b)²) = ...

After n applications:

= lim n!/(bˣ (ln b)ⁿ) = 0

Each differentiation reduces the polynomial's degree by 1 but leaves the exponential as an exponential. Eventually the numerator is constant, the denominator still grows, and the limit is zero.

The Hierarchy of Growth

From slowest to fastest as x → ∞:

- Logarithmic: ln(x), log₁₀(x)

- Polynomial: x^0.5, x, x², x³, x¹⁰⁰

- Exponential: 1.01ˣ, 2ˣ, 10ˣ, eˣ

- Super-exponential: xˣ, x^(xˣ), tower functions

Within each category, larger parameters mean faster growth. But a slow exponential still beats any polynomial.

lim(x→∞) x¹⁰⁰⁰ / 1.001ˣ = 0

A base barely above 1 still wins against a degree of 1000.

Practical Implications

Computer Science: Algorithm Complexity

- O(n²) algorithm with n = 1000: 1,000,000 operations

- O(n³) algorithm with n = 1000: 1,000,000,000 operations

- O(2ⁿ) algorithm with n = 30: about 1,000,000,000 operations

- O(2ⁿ) algorithm with n = 50: about 1,000,000,000,000,000 operations

Polynomial algorithms are tractable for large inputs. Exponential algorithms quickly become impossible.

This is why computer scientists care so much about P vs NP. If a problem requires exponential time, no amount of hardware saves you.

Finance: Compound Growth

Polynomial growth: add $100/year. After 30 years: $3,000.

Exponential growth at 7%: double every 10 years. After 30 years, each dollar becomes $8.

Exponential investing beats linear saving—dramatically.

Biology: Population Dynamics

Linear growth (constant birthrate): population increases steadily.

Exponential growth (births proportional to population): population explodes.

Early in population growth (abundant resources), exponential applies. This is why small populations can become large populations quickly.

Technology Adoption and Network Effects

Social networks, messaging apps, and platforms grow exponentially in their viral phase. Each user recruits more users, who recruit more users. Polynomial marketing budgets can't compete with exponential word-of-mouth.

This is why tech startups obsess over "hockey stick growth"—they're looking for the phase transition from polynomial to exponential. Companies with exponential user acquisition eat companies with linear customer acquisition.

Debt Spirals

Credit card debt at 20% annual interest:

- Year 0: $10,000

- Year 5: $24,883

- Year 10: $61,917

- Year 20: $383,376

Meanwhile, if you paid $200/month linearly toward the debt, you'd have paid $48,000 over 20 years. The exponential interest outpaces linear payments, which is why minimum payments barely dent high-interest debt.

The Crossover Point

For any polynomial p(x) and exponential bˣ (b > 1), there exists some x₀ beyond which bˣ > p(x) permanently.

Finding this crossover:

2ˣ = x¹⁰

This doesn't have a nice closed form, but numerical methods find x₀ ≈ 58.8.

For x > 59, 2ˣ dominates x¹⁰ forever.

The higher the polynomial degree, the larger the crossover point—but the crossover always exists.

Some examples of crossover points:

| Polynomial | Exponential | Crossover |

|---|---|---|

| x² | 2ˣ | x ≈ 4 |

| x³ | 2ˣ | x ≈ 10 |

| x¹⁰ | 2ˣ | x ≈ 59 |

| x¹⁰⁰ | 2ˣ | x ≈ 614 |

| x¹⁰ | 1.1ˣ | x ≈ 371 |

Notice that even a very slow exponential (base 1.1) eventually catches x¹⁰. It just takes longer. The eventual dominance is inevitable; only the timing changes.

This has a practical lesson: if you're in a race between polynomial and exponential processes, the exponential will win eventually. The only question is whether "eventually" matters for your time horizon.

Logarithms: The Slowpoke

Logarithms grow slower than any polynomial:

lim(x→∞) (ln x)ⁿ / xᵉ = 0 for any ε > 0

Even (ln x)¹⁰⁰⁰ is eventually beaten by x^0.001.

This is the flip side of "exponential beats polynomial." Taking logs inverts the hierarchy.

The Intuition

Polynomial growth is additive at heart. Going from x to x+1 adds roughly nx^(n-1) to xⁿ. The amount added grows, but it's always a finite addition.

Exponential growth is multiplicative. Going from x to x+1 multiplies bˣ by b. A constant factor, applied repeatedly.

Repeated multiplication dominates repeated addition. That's why exponentials win.

Summary Table

| Comparison | Result | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polynomial vs polynomial | Higher degree wins | x³ beats x² |

| Exponential vs exponential | Larger base wins | 3ˣ beats 2ˣ |

| Exponential vs polynomial | Exponential wins | 1.001ˣ beats x¹⁰⁰⁰ |

| Logarithm vs polynomial | Polynomial wins | x^0.01 beats (ln x)¹⁰⁰ |

Why This Matters

The dominance of exponentials over polynomials explains:

- Why compound interest beats savings

- Why exponential algorithms are intractable

- Why epidemics seem to explode overnight

- Why Moore's Law was so transformative

- Why debt spirals out of control

Any time you're comparing multiplicative and additive processes, bet on multiplicative. The exponential always wins—it's just a matter of when.

Part 7 of the Exponential Functions series.

Previous: The Exponential Function eˣ: The Most Important Function in Mathematics Next: Synthesis: Exponentials as the Language of Multiplicative Processes

Comments ()