FEP Implementations: From Theory to Working Systems

FEP Implementations: From Theory to Working Systems

Series: The Free Energy Principle | Part: 9 of 11

Theory is elegant. Implementation is messy.

The Free Energy Principle makes beautiful claims: brains minimize surprise, action fulfills predictions, hierarchical models process the world. But does the math actually work when you try to build systems that operate this way?

The answer: sometimes spectacularly, sometimes not at all.

Over the past decade, researchers have built FEP-based models for everything from visual processing to robotic control to psychiatric diagnosis. Some implementations vindicate the theory. Others reveal where formalism meets reality and breaks.

Let's look at what actually works.

Predictive Coding in Visual Cortex

The claim: Visual cortex implements hierarchical predictive coding, with higher areas predicting lower areas and only errors propagating upward.

The implementation: Rao and Ballard (1999) built a computational model where V1 neurons encode prediction errors between expected and actual visual input, with higher visual areas (V2, V4) sending predictions down.

What works:

- The model explains extraclassical receptive field effects (neurons responding to context outside their classical receptive field)

- It predicts distinct prediction and error neurons (found in different cortical layers)

- It accounts for top-down modulation of visual responses

- It explains why most cortical connections are feedback (carrying predictions)

What doesn't: The model requires hand-tuned priors and doesn't learn hierarchical representations as well as modern deep learning. It's a proof of concept, not a full visual system.

Verdict: Successful as neuroscientific model; limited as engineering solution.

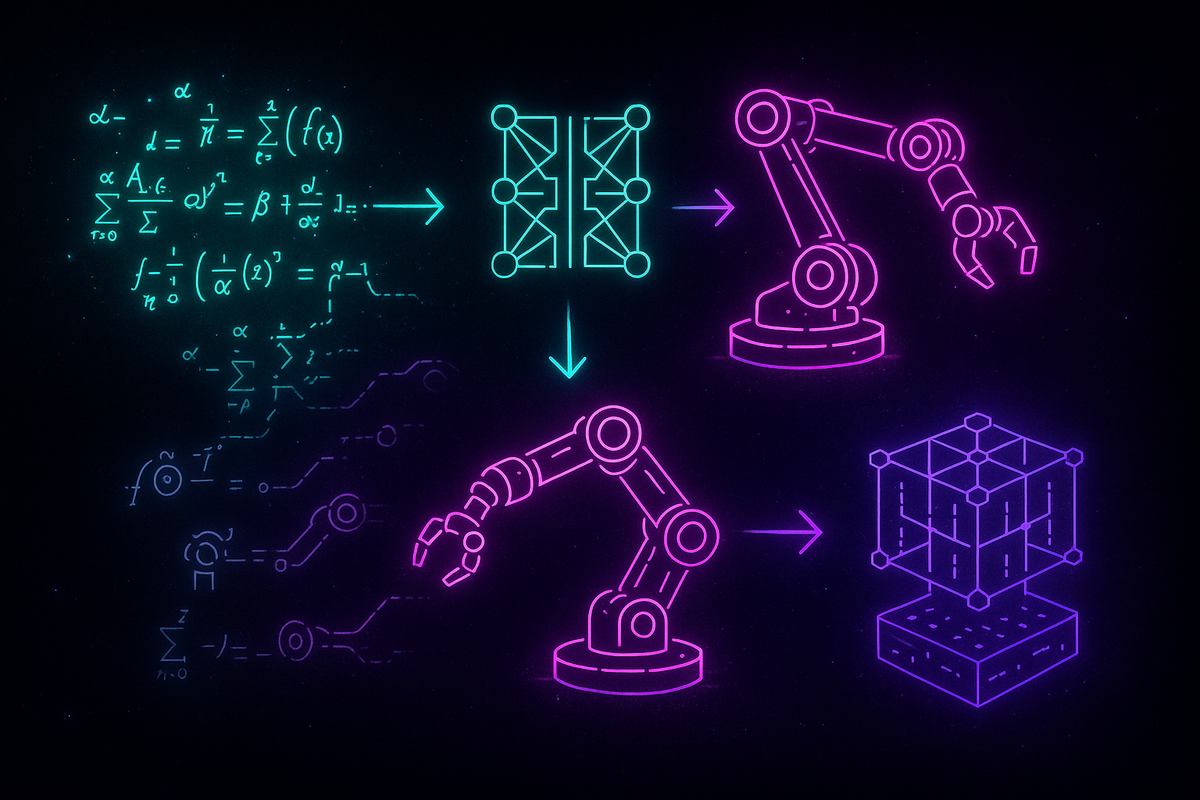

Active Inference for Robotic Control

The claim: Motor control can be implemented as active inference—predicting proprioceptive targets and letting reflexes minimize error.

The implementation: Friston and colleagues have built active inference controllers for robotic arms and simulated agents. Instead of computing motor commands directly, the system:

- Predicts desired proprioceptive state (e.g., "arm extended")

- Computes error between predicted and actual proprioception

- Issues motor commands that minimize error

What works:

- Agents successfully reach targets, navigate mazes, and perform sequential tasks

- The approach naturally handles uncertainty (noisy sensors, unpredictable environments)

- It unifies perception and action in a single framework

- Policies emerge from expected free energy minimization without explicit reward engineering

What doesn't:

- Computationally expensive compared to standard optimal control

- Requires careful tuning of precision parameters

- Struggles with very high-dimensional action spaces

- Not yet competitive with state-of-the-art reinforcement learning on complex tasks

Verdict: Promising for robotics requiring tight sensorimotor coupling; not yet ready for general AI.

PyMDP and SPM: Software Tools

Several software packages implement active inference and FEP:

SPM (Statistical Parametric Mapping): Friston's lab developed DCM (Dynamic Causal Modeling) toolbox, which fits FEP models to neuroimaging data. Widely used in computational psychiatry and neuroscience.

PyMDP: Python library for discrete-state active inference. Allows researchers to build agents with generative models, compute expected free energy, and simulate behavior.

What works: These tools make FEP accessible to researchers without deep math backgrounds. They've enabled hundreds of studies testing FEP predictions in neural and behavioral data.

What doesn't: Steep learning curve. Many hyperparameters. Results can be sensitive to model specification. Risk of overfitting complex models to limited data.

Verdict: Valuable research tools; require expertise to use well.

Computational Psychiatry Applications

The claim: Mental illness reflects dysfunctional inference—either poor priors, misweighted precision, or maladaptive generative models.

The implementation: Researchers have built FEP models of:

- Autism: Over-weighting sensory evidence (low prior precision), leading to unpredictability and preference for routine

- Schizophrenia: Over-weighting priors (low sensory precision), leading to hallucinations and delusions

- Depression: High expected free energy for all policies, leading to behavioral inactivation

- Anxiety: Over-predicting threat, leading to hypervigilance and avoidance

What works:

- FEP provides a unifying framework for understanding diverse psychopathologies

- Models generate testable predictions about neural and behavioral differences

- Some experimental support (e.g., reduced mismatch negativity in schizophrenia consistent with low sensory precision)

What doesn't:

- Models are often qualitative or fitted post hoc

- Harder to distinguish FEP accounts from competing theories without direct neural measurements

- Risk of explaining everything without predicting anything specific

Verdict: Productive framework for generating hypotheses; needs more direct empirical tests.

Deep Learning Meets FEP

Can FEP improve deep learning, or vice versa?

Predictive coding networks: Some researchers have built neural networks inspired by FEP, using bidirectional connections and error-correction dynamics.

What works:

- Predictive coding networks can learn hierarchical representations

- They handle uncertainty better than standard feedforward networks

- They're more biologically plausible (separate error and prediction units)

What doesn't:

- Training is slower than backpropagation

- Performance on standard benchmarks (ImageNet, etc.) doesn't yet match state-of-the-art deep learning

- Unclear whether biological plausibility buys practical advantages

Alternative approach: Use deep learning to learn generative models, then use active inference for control. This hybrid approach shows promise—leverage deep learning's representation power with FEP's uncertainty handling and action selection.

Verdict: Interesting research direction; not yet practically superior to standard methods.

Where Implementations Struggle

Several challenges recur across FEP implementations:

1. Computational cost: Variational inference is iterative and expensive. Real-time performance requires approximations that sacrifice optimality.

2. Model specification: FEP requires defining a generative model (what causes what). For complex domains, this is hard. You either hand-craft the model (limiting generality) or learn it (requiring vast data).

3. Precision weighting: Attention and learning depend on setting precision correctly. But how does the brain know what precision to assign? This is an open problem.

4. Scalability: FEP works well for small discrete state spaces or simple continuous systems. Scaling to high-dimensional perception-action loops (e.g., humanoid robotics) remains challenging.

5. Biological realism vs. engineering performance: FEP aims for biological plausibility, but biology isn't optimized for artificial tasks. Sometimes less biologically realistic methods work better in practice.

Where Implementations Succeed

Despite challenges, FEP implementations excel at:

Unified perception-action: Systems that must tightly couple sensing and acting (e.g., adaptive robots, sensorimotor prosthetics) benefit from FEP's integrated framework.

Uncertainty quantification: FEP naturally handles noisy, ambiguous, or missing data by maintaining probabilistic beliefs.

Neuroscience models: FEP provides principled frameworks for modeling neural data, generating testable hypotheses about circuit function.

Computational psychiatry: FEP offers a common language for understanding diverse psychopathologies as inference failures.

The Meta-Lesson

FEP is not a silver bullet for AI or neuroscience. But it's a productive framework:

- It generates specific, testable models

- It unifies previously separate phenomena

- It suggests novel architectures and algorithms

- It connects biology to engineering

The gap between theory and implementation is where science happens. Every failed implementation teaches us something about where the formalism needs refinement.

And every successful implementation—visual predictive coding, active inference robots, computational psychiatry models—validates a piece of the larger FEP picture.

Further Reading

- Rao, R. P., & Ballard, D. H. (1999). "Predictive coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects." Nature Neuroscience, 2(1), 79-87.

- Friston, K., FitzGerald, T., Rigoli, F., Schwartenbeck, P., & Pezzulo, G. (2017). "Active inference: a process theory." Neural Computation, 29(1), 1-49.

- Da Costa, L., Parr, T., Sajid, N., Veselic, S., Neacsu, V., & Friston, K. (2020). "Active inference on discrete state-spaces: a synthesis." Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 99, 102447.

- Schwartenbeck, P., FitzGerald, T., Mathys, C., Dolan, R., & Friston, K. (2015). "The dopaminergic midbrain encodes the expected certainty about desired outcomes." Cerebral Cortex, 25(10), 3434-3445.

- Parr, T., Pezzulo, G., & Friston, K. J. (2022). Active Inference: The Free Energy Principle in Mind, Brain, and Behavior. MIT Press.

This is Part 9 of the Free Energy Principle series, exploring how FEP translates from mathematical formalism to working implementations.

Previous: Critics and Controversies

Next: Synthesis: The Free Energy Principle and the Geometry of Coherence

Comments ()