Fiction as Cultural Imagination Technology

Every culture tells stories about what might be possible.

The Mesopotamians imagined Gilgamesh seeking immortality. The Greeks imagined Daedalus building wings. The medieval Europeans imagined holy grails and philosopher's stones. The Enlightenment imagined utopias of reason.

These aren't just entertainment. They're collective simulations—shared thought experiments about what the world allows.

Science fiction continues this tradition with a specific constraint: the stories must be naturalistic. The possibilities must flow from scientific and technological extrapolation, not from magic or divine intervention.

This makes science fiction a peculiar kind of cultural technology—one that processes what science means for human possibility.

Why Societies Tell Stories

Storytelling is not optional for humans. It's obligatory.

Narrative is how we organize experience. We don't perceive the world as raw data—we perceive it as stories with characters, causation, and consequence. The brain is a narrative engine.

But individual narratives face a limitation: they're constrained by individual experience. You can only imagine what you've encountered, what you've been told, what you've combined from your own inputs.

Collective storytelling expands the possibility space. When stories are shared, refined, elaborated by many minds, they explore territories no individual could reach alone.

This is why mythologies exist in all cultures. They're not just entertainment—they're distributed computing systems for exploring possibility.

Fiction as Simulation

Here's a way to understand what fiction does: it simulates scenarios that haven't happened yet.

A pilot practices in a flight simulator before flying real passengers. The simulator provides experience without risk. Mistakes are recoverable. Edge cases can be explored.

Fiction does the same thing for cultural possibility.

What if we could travel to other worlds? What if machines could think? What if we lived forever? What if society collapsed?

These scenarios are simulated in narrative form. Characters navigate the imagined worlds. Consequences unfold. The culture learns from simulations what might matter in realities it hasn't yet encountered.

Science fiction is the flight simulator for futures we haven't reached.

The Imagination Constraint

Fiction can imagine anything—dragons, gods, time loops, parallel selves. But science fiction operates under a constraint: the imaginings must feel naturalistic.

Not realistic in the sense of being probable—most sci-fi scenarios are wildly improbable. Naturalistic in the sense of flowing from physical law, technological development, or social evolution.

This constraint matters because it tethers imagination to the actual world. The stories are "what if" within the laws of nature, not "what if magic worked."

This is why science fiction tracks scientific paradigm. The imagination is constrained by what science says is possible. When science changes what's thinkable, fiction changes what's imaginable.

The Paradigm Filter

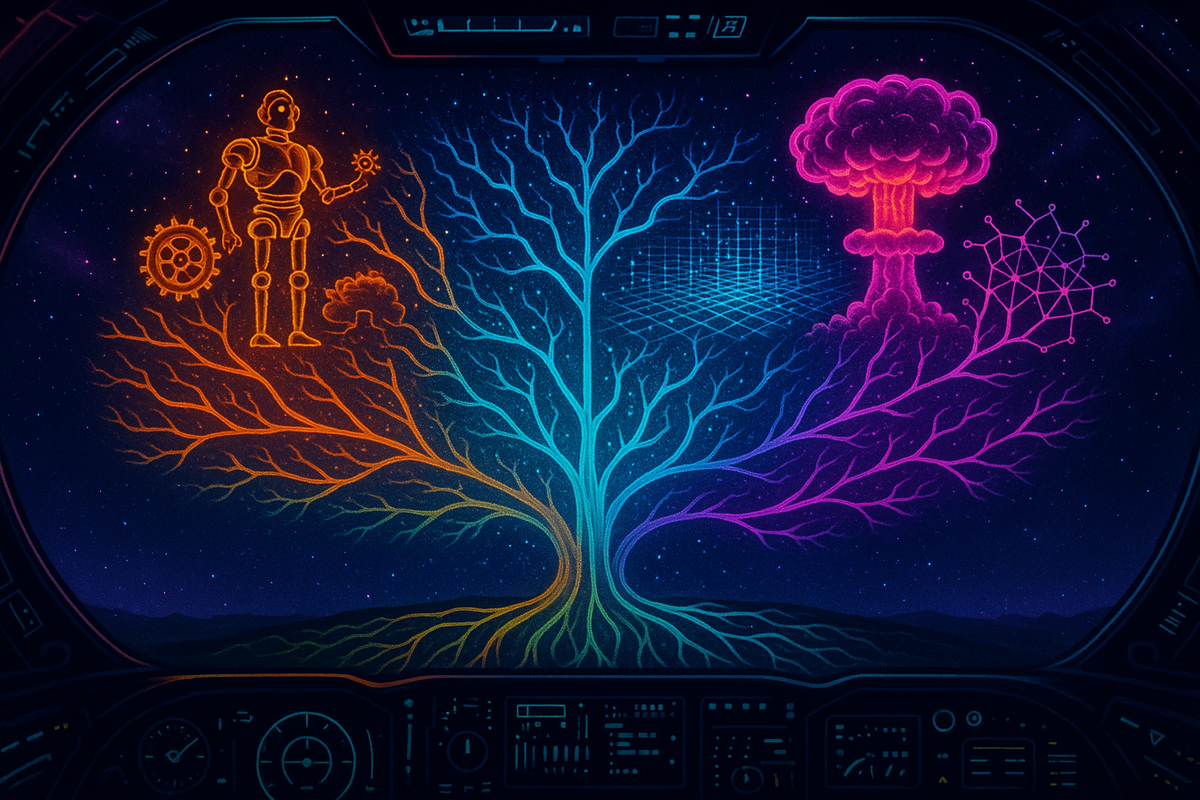

Every era's science fiction reflects that era's scientific framework.

The mechanical age (17th-19th century) gave us clockwork automata, predictable utopias, and stories where rational planning could control outcomes. The universe was a machine; fiction imagined what machines could do.

The thermodynamic age (19th century) gave us heat death anxieties, entropy narratives, and the sense that systems run down. Wells' The Time Machine ends with the sun growing dim.

The electromagnetic age (late 19th-early 20th century) gave us communication at a distance—radio, telepathy, transmission of mind. The invisible forces became characters.

The nuclear age (mid-20th century) gave us apocalypse, mutation, and the sense that technology could end everything. Power became dangerous.

The information age (late 20th century) gave us virtual reality, AI, and the question of whether minds are programs.

The complexity age (21st century) gives us emergence, network effects, and systems that no one controls.

Each paradigm filters imagination. You can only imagine what you have concepts for.

The Possibility Space

Here's the key insight: science fiction doesn't just reflect what science believes is true. It explores the possibility space that science opens up.

Newtonian mechanics makes certain things possible (space travel via rockets) and certain things impossible (faster-than-light travel without exotic physics). Science fiction explores the possible, pushes at the impossible, and occasionally proposes workarounds.

The possibility space is not just technical. It's metaphysical.

If the universe is deterministic, what does that mean for free will? If consciousness is computation, what does that mean for identity? If reality is observer-dependent, what does that mean for truth?

Science fiction is the cultural space where these questions get narrative form. Not as philosophy—as lived experience of characters navigating imagined implications.

Why This Matters

Understanding fiction as imagination technology changes how you read it.

The naive reading: "This is a fun story about robots."

The paradigmatic reading: "This story explores what it means if cognition is substrate-independent. The robot plot is a narrative vehicle for a philosophical proposition about mind."

Both readings are valid. But the second one explains why certain stories persist, why certain themes recur, and why science fiction changes when science changes.

The stories we tell about possibility reveal what we believe about reality.

A culture that believes in deterministic physics tells different stories than a culture that believes in quantum indeterminacy. A culture that believes consciousness is biological tells different stories than a culture that believes consciousness is computational.

Read the fiction. See the worldview.

The Mirror Function

Science fiction serves as a mirror for the collective imagination.

Not a distorting mirror—a revealing one. The stories show what a culture believes is possible, what it fears, what it hopes for, what metaphysical framework it's operating within.

This mirror function explains why science fiction often predates technological development. Not because fiction predicts—but because fiction reveals what a culture is already thinking about.

Submarines existed in fiction before they existed in reality. Space travel was imagined before rockets. Artificial intelligence was narrative before it was engineering.

The imagination runs ahead of the technology. And the imagination is constrained by the paradigm.

The Project of This Series

This series reads science fiction paradigmatically.

We'll examine how specific scientific frameworks shape specific fictional universes. How Newtonian mechanics creates deterministic plots. How chaos theory creates sensitive-dependence plots. How quantum mechanics creates branching plots.

We'll look at specific cases: Herbert's Dune reflecting complexity theory. The Matrix reflecting late-90s physics. The MCU reflecting quantum multiverse popularization.

We'll see how the mirror works—how fiction reveals not just what a culture imagines, but what it believes about the nature of choice, causality, and consequence.

The thesis: science fiction is a diagnostic tool. Show me what stories a culture tells about possibility, and I'll show you what that culture believes about reality.

Further Reading

- Suvin, D. (1979). Metamorphoses of Science Fiction. Yale University Press. - Jameson, F. (2005). Archaeologies of the Future. Verso. - Csicsery-Ronay, I. (2008). The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction. Wesleyan University Press.

This is Part 1 of the Science Fiction Mirror series. Next: "Determinism to Chaos: How Physics Changed Plot."

Comments ()