The First Law: Energy Cannot Be Created or Destroyed

In the early 1840s, a young German physician named Julius Robert Mayer was working as a ship's doctor in the tropics. He noticed something odd: when he bled patients in Java, their venous blood was unusually red—almost as bright as arterial blood.

Mayer knew that blood color relates to oxygen content. In cold climates, venous blood is dark because the body has extracted more oxygen to generate heat. In the tropics, less oxygen is needed for heat, so venous blood stays redder.

But this observation led Mayer to a profound insight: heat and mechanical work are the same thing—different forms of one underlying quantity. The body burns food to produce heat OR work. The total is conserved.

This was the first clear statement of the First Law of Thermodynamics, published in 1842. It would take decades for the physics community to recognize its importance. But Mayer had discovered that the universe keeps perfect books.

The Law

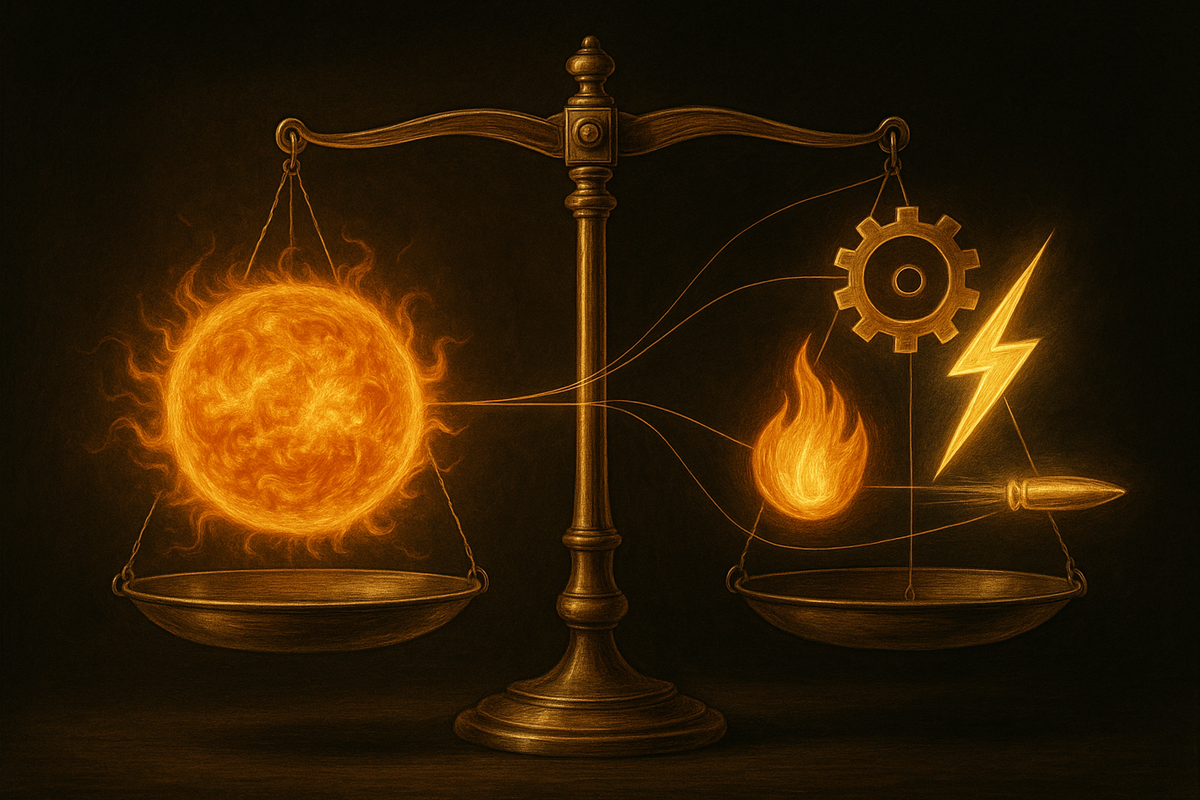

The First Law of Thermodynamics states: Energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed from one form to another.

Mathematically: ΔU = Q - W

Where: - ΔU is the change in internal energy - Q is heat added to the system - W is work done by the system

The total energy of an isolated system remains constant. Energy in equals energy out plus change in stored energy. No exceptions.

The pebble: The universe doesn't do free lunches. Every output requires an input. The books always balance.

What Is Energy?

Energy is physics' most abstract concept. We can't see it directly—we only see its effects. But it turns out to be the one quantity nature refuses to create or destroy.

Energy comes in many forms: - Kinetic: Moving objects - Potential: Position in a force field (gravitational, electric) - Thermal: Random motion of particles - Chemical: Bonds between atoms - Nuclear: Binding energy in atomic nuclei - Electromagnetic: Light, radio waves, X-rays - Mass: E=mc² (mass is concentrated energy)

The First Law says all these forms are fungible. Convert any one into any other. The total stays the same.

The Mechanical Equivalent of Heat

Before the First Law, scientists thought heat was a substance called "caloric" that flowed between objects. Hot things had more caloric; cold things had less. This explained a lot but predicted that mechanical work couldn't create heat—only transfer it.

James Prescott Joule disproved caloric theory with a brilliant experiment in the 1840s. He built an apparatus where falling weights turned paddles in a tank of water. The mechanical work (falling weights) became thermal energy (water heating up). No caloric transfer—just conversion.

Joule measured the conversion rate precisely: 4.184 joules of mechanical work produce exactly 1 calorie of heat. This number—the mechanical equivalent of heat—proved that heat and work are the same thing in different forms.

The pebble: The mechanical equivalent of heat killed the caloric theory and birthed conservation of energy. One careful experiment collapsed centuries of wrong thinking.

Conservation in Action

A Cup of Coffee

Your hot coffee has thermal energy (fast-moving molecules). It's surrounded by cooler air. Heat flows from coffee to air until equilibrium. The coffee loses thermal energy; the air gains it. Total conserved.

A Car Engine

Gasoline has chemical energy (bonds between atoms). Combustion converts this to thermal energy (hot gas). The hot gas expands, pushing pistons—converting thermal to kinetic energy. The kinetic energy moves the car, eventually dissipating as heat (friction, air resistance). At every step, total energy is conserved.

You Reading This

Light energy hits your retina, becoming electrochemical signals. Your neurons fire, burning ATP. The ATP came from glucose oxidation. The glucose came from food. The food's energy came from photosynthesis. The sunlight came from nuclear fusion in the sun. Every step: conserved.

The pebble: Trace any energy backward and it leads to the Big Bang. Trace it forward and it eventually becomes ambient heat. But at every instant, the total is constant.

Perpetual Motion Machines of the First Kind

The First Law explicitly forbids perpetual motion machines of the first kind—devices that produce work from nothing or create energy from nowhere.

Every such machine ever proposed or built has failed. Not some—all. The history of perpetual motion is a history of fraud, error, and wishful thinking.

Famous examples: - Bhaskara's wheel (12th century): Weighted wheel that supposedly turns forever. Doesn't work—angular momentum conserves, friction dissipates. - Orffyreus's wheel (1712): Claimed to run indefinitely. Was later revealed to have a hidden hand crank operated by the inventor's maid. - Modern "free energy" devices: All either don't work, have hidden energy inputs, or are measuring errors.

The pebble: The Patent Office explicitly refuses to examine perpetual motion patent applications. The First Law has held for 180 years. They're not going to break it for your clever design.

The First Law vs. Other Conservation Laws

Conservation of energy isn't the only conservation law in physics: - Conservation of momentum - Conservation of angular momentum - Conservation of electric charge - Conservation of baryon number - Conservation of lepton number

But energy conservation is special because it connects to time. Emmy Noether proved in 1915 that every conservation law corresponds to a symmetry of nature. Energy conservation follows from time-translation symmetry—the laws of physics being the same today as tomorrow.

The pebble: The First Law holds because the universe is consistent through time. If physics changed from moment to moment, energy wouldn't be conserved.

Einstein's Addendum: E=mc²

In 1905, Einstein showed that mass is a form of energy. A kilogram of mass "contains" 9×10¹⁶ joules of energy. This is why nuclear reactions release such enormous power—they're converting a tiny bit of mass into energy.

The First Law still holds with this addendum. Mass-energy is conserved. When uranium fissions, the products weigh slightly less than the reactants—the missing mass became the energy of the explosion.

The pebble: Hiroshima converted about 0.6 grams of mass into energy. That's it—half a paperclip. E=mc² is not abstract.

Why the First Law Isn't Enough

The First Law is necessary but not sufficient for understanding thermodynamics. It tells you energy is conserved but not which processes actually happen.

Consider: you drop a ball, it hits the ground and stops. Kinetic energy became thermal energy (heat in the ball and floor). That's fine—energy conserved.

Now imagine the reverse: the floor spontaneously cools down slightly, and that thermal energy becomes kinetic energy, launching the ball back up. Energy would still be conserved. But this never happens.

The First Law permits both directions. The Second Law is what picks the actual direction. We need both laws to understand reality.

Internal Energy

The First Law introduces a crucial concept: internal energy (U). This is the total energy contained within a system—kinetic energy of all molecules, potential energy of molecular interactions, bond energies.

You can't measure internal energy directly. But you can measure changes in internal energy (ΔU) by tracking heat (Q) and work (W).

For a gas in a cylinder: - Heat the gas (add Q): internal energy increases - Let the gas expand (do work W): internal energy decreases - Net change: ΔU = Q - W

This bookkeeping is the First Law in practice. Track all the inputs and outputs. The change in stored energy is what's left.

Enthalpy: Energy at Constant Pressure

Most real-world processes happen at constant pressure (atmospheric pressure). This makes work calculation awkward because the system can expand or contract against the atmosphere.

Chemists define enthalpy (H) as H = U + PV, where P is pressure and V is volume. At constant pressure, the change in enthalpy (ΔH) equals the heat absorbed: ΔH = Q.

This is why you see enthalpy in chemistry tables. It's the useful form of the First Law for reactions in open beakers.

Thermodynamic Cycles

A thermodynamic cycle returns a system to its initial state. Since the system ends where it started, ΔU = 0 over the cycle. By the First Law, this means the net work output equals the net heat input: W_net = Q_net.

This is how engines work: 1. Heat added at high temperature (Q_in) 2. Work extracted (W_out) 3. Heat rejected at low temperature (Q_out) 4. Return to start

First Law: Q_in = W_out + Q_out

The First Law constrains the energy flow but doesn't say how much work you can extract. For that, you need the Second Law and its efficiency limits.

Philosophical Implications

The First Law makes a profound statement: the universe has a fixed energy budget. We're not creating or destroying—just rearranging.

Every action you take, every thought you think, is part of a chain of energy transformations that began at the Big Bang and will continue until heat death. The total never changes. The forms constantly shift.

There's something both humbling and elegant about this. We're not exempt from conservation. Neither are stars, galaxies, or black holes. The same laws apply everywhere, every time.

The pebble: The universe's energy was set at the Big Bang. Everything since—stars forming, life emerging, you reading this—is just that energy changing costumes.

Further Reading

- Feynman, R. (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1, Chapter 4 (Conservation of Energy). - Atkins, P. (2010). The Laws of Thermodynamics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. - Cropper, W. H. (2001). Great Physicists. Oxford University Press. (Chapters on Mayer, Joule, Helmholtz)

This is Part 3 of the Laws of Thermodynamics series. Next: "The Second Law: Why Time Has a Direction"

Comments ()