From Theory to Code: The Active Inference Implementation Revolution

From Theory to Code: The Active Inference Implementation Revolution

Series: Active Inference Applied | Part: 1 of 10

In 2010, Karl Friston published a paper claiming that everything from bacterial chemotaxis to human consciousness operates on the same mathematical principle: organisms minimize the gap between what they expect and what they experience. By 2020, researchers were using these equations to build robots that navigate uncertainty, AI agents that plan in open-ended environments, and computational models of psychiatric disorders. By 2025, active inference had moved from theoretical neuroscience into working implementations—code running on hardware, agents acting in real environments, systems that learn by doing.

This isn't just another AI framework. It's a shift from hand-coding behaviors to specifying how agents should think about the world. From reward functions to world models. From optimization to inference. From training on massive datasets to learning through interaction.

And it's happening now. Not in the distant future, not in research labs alone, but in repositories, competitions, and deployed systems. Active inference is becoming the actual math behind next-generation AI agents.

The Gap Between Theory and Implementation

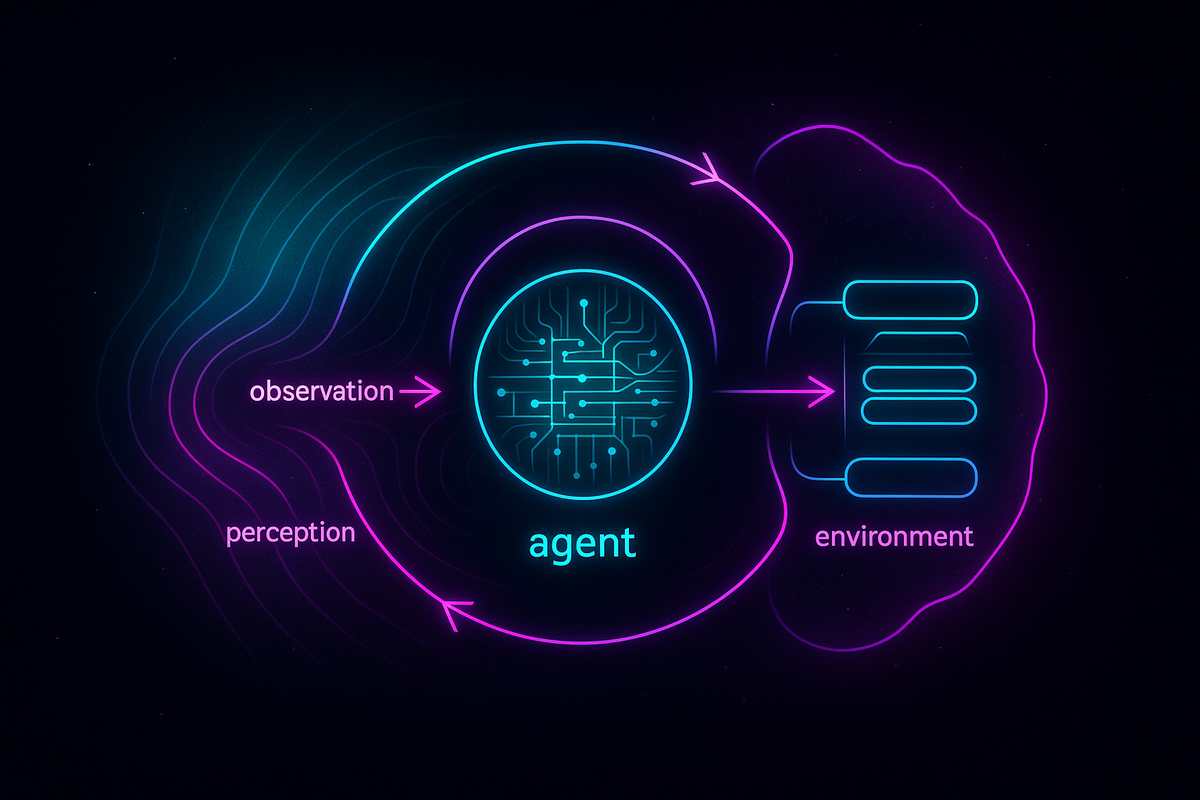

The theory is elegant. Living systems minimize variational free energy—a measure of surprise or prediction error. They do this by building generative models (internal representations of how the world works) and then using these models to both perceive the world (inference) and act on it (action). Perception updates beliefs. Action changes the world to match expectations. The mathematics is rigorous, grounded in information geometry and Bayesian inference.

The implementation is hard. How do you actually construct a generative model for a complex environment? How do you discretize continuous state spaces without losing essential structure? How do you compute expected free energy—the objective function that guides planning—in real time? How do you balance epistemic value (information gain) against pragmatic value (goal achievement) when deciding what to do next?

These aren't just engineering details. They're the gap between a beautiful theory and a working system.

For years, that gap kept active inference in the realm of theoretical neuroscience and mathematical biology. Researchers could write papers about the Free Energy Principle. They could model specific phenomena—like saccadic eye movements or sensory attenuation. But building a general-purpose active inference agent that actually worked in novel environments? That was different.

What changed? Implementation frameworks emerged. Code libraries that handle the mathematical machinery. Standardized architectures that translate theory into algorithms. Benchmarks that test whether agents actually do what the math says they should. And most importantly: a community of researchers and engineers willing to bridge the abstraction gap.

Why Active Inference Matters for AI

The dominant paradigm in AI is reward maximization: specify a reward function, train an agent to maximize expected reward through trial and error. This works—spectacularly well for games, robotics tasks, and constrained environments.

But it has limits:

Reward specification is fragile. If the reward function doesn't perfectly capture what you want, the agent optimizes for the specified reward in ways you didn't intend. This is the alignment problem in miniature.

Sample efficiency is poor. Reinforcement learning agents need massive amounts of experience to learn even simple behaviors. They don't generalize well to variations of the training environment.

Exploration is hard. Agents struggle to balance exploring unknown parts of the state space against exploiting known rewards. Curiosity-driven methods help, but they're often ad hoc additions rather than fundamental.

Planning is expensive. Model-based RL agents build world models, but using them for planning requires expensive tree searches or trajectory optimization. They don't naturally integrate perception and action.

Active inference offers different answers:

Agents minimize surprise, not maximize reward. The objective is epistemic: reduce uncertainty about the world. Goals emerge from the generative model—specifically, from preferred observations that the agent expects to encounter. This inverts the reward problem: instead of specifying what to maximize, you specify what states the agent should expect itself to be in.

Learning is structured by the generative model. The agent doesn't learn arbitrary stimulus-response mappings. It learns the causal structure of the world—how actions affect states, how states generate observations. This structure enables generalization.

Exploration is intrinsic. Active inference agents naturally seek information. Expected free energy includes an information gain term—epistemic value—that drives exploration without requiring separate curiosity mechanisms. Agents explore to reduce uncertainty about their model.

Planning is inference. Instead of searching through action sequences, active inference agents infer probable trajectories that would minimize expected free energy. Planning becomes belief propagation in a probabilistic graphical model. It's computationally efficient and integrates seamlessly with perception.

This isn't just theoretically elegant. It changes what kinds of problems you can solve.

From Neuroscience to Robotics: Implementation Bridges

The first active inference implementations focused on replicating specific neuroscience phenomena. Simulate how saccades reduce uncertainty about visual scenes. Model how action cancels sensory prediction error during movement. Show that dopamine might encode precision-weighted prediction errors.

These models were impressive but constrained. They validated the theory against known biology. They didn't yet demonstrate that active inference could scale to general-purpose agents in novel environments.

That required new architectures:

Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs) as generative models. A POMDP specifies states, observations, actions, transition dynamics, and observation likelihoods. Active inference agents treat these as the structure of their generative model. Given a POMDP, they can infer beliefs about hidden states (perception), infer probable action sequences (planning), and update their model structure (learning).

Message passing for belief propagation. Computing posterior beliefs over states and policies requires inference in graphical models. Message passing algorithms—especially variational message passing—make this tractable. Instead of exact Bayesian inference (often intractable), agents perform approximate inference by passing messages between nodes in a factor graph.

Discrete state spaces for tractability. Continuous state spaces require discretization or functional approximations. Many implementations use discrete states with categorical distributions. This sacrifices some representational richness but gains computational efficiency. Others use deep networks to parameterize continuous distributions.

Expected free energy as policy prior. Instead of sampling actions from a learned policy (as in RL), active inference agents infer policies by minimizing expected free energy. Policies that reduce expected uncertainty (epistemic) and expected deviation from preferred observations (pragmatic) become more probable. The agent then samples from this posterior over policies.

These architectural choices aren't arbitrary. They're principled translations of the theory into computational machinery.

The Tooling Revolution

Implementation frameworks have matured rapidly:

pymdp (Python): A library for discrete active inference agents. Provides tools for specifying generative models as POMDPs, computing expected free energy, performing belief updates via message passing, and running simulations. Designed for research and education. Well-documented, modular, accessible to researchers without deep ML engineering experience.

SPM DEM (MATLAB): Part of Statistical Parametric Mapping toolkit from the Wellcome Centre (where Friston works). Implements Dynamic Expectation Maximization for continuous-time active inference. Used primarily in computational neuroscience and computational psychiatry. Powerful but steep learning curve.

RxInfer.jl (Julia): A library for reactive message passing in probabilistic graphical models. Supports active inference through factor graphs and variational message passing. Emphasizes efficiency, composability, and real-time inference. Emerging as a tool for deploying active inference in robotics and control.

Deep active inference frameworks: Neural network implementations that use deep learning to parameterize generative models and inference networks. Combines active inference principles with the representational power of deep learning. Less theory-pure, more pragmatic for complex observations like images.

These tools handle the mathematical heavy lifting. Researchers can focus on model design—what generative model makes sense for this environment—rather than reimplementing belief propagation from scratch.

Real Implementations, Real Results

Active inference agents have been tested in:

Grid worlds and navigation tasks: Agents learn spatial maps, plan routes that minimize expected free energy, balance exploration and exploitation naturally. They outperform pure reward-based methods in sample efficiency—learning coherent behavior from fewer interactions.

Arm reaching and motor control: Robotic arms controlled via active inference minimize proprioceptive prediction error. The agent learns inverse models (how to move to reach targets) and forward models (how movements change proprioception) simultaneously. Movements are smooth, adaptive, robust to perturbations.

Dialogue and communication: Agents model conversational dynamics as POMDPs. They infer what the other agent believes based on utterances and select communicative acts that reduce mutual uncertainty. This produces cooperative dialogue without explicit training on conversation datasets.

Foraging and resource gathering: Agents navigate environments to collect resources. They balance epistemic exploration (discovering new resource locations) with pragmatic exploitation (harvesting known resources). The balance emerges from expected free energy, not hand-tuned heuristics.

Psychiatric modeling: Active inference models of delusions (overconfident priors), anxiety (elevated precision on threat-related predictions), and autism (atypical precision weighting) have been implemented as computational agents. These models make testable predictions about behavior under uncertainty.

The pattern: active inference agents learn structured, generalizable behaviors from sparse experience. They don't just fit training data. They build causal models and use them to act intelligently in novel situations.

The Deep Learning Integration

One criticism of early active inference implementations: they required hand-specifying the generative model. For simple environments (grid worlds, low-dimensional state spaces), this is feasible. For complex, high-dimensional observations—images, audio, natural language—it's not.

This is where deep active inference enters. Instead of manually defining observation likelihoods and transition dynamics, use neural networks to learn them:

Encoder networks map observations to beliefs over latent states (approximate posterior inference).

Decoder networks generate predicted observations from latent states (generative model).

Transition networks predict how latent states evolve with actions (dynamics model).

Policy networks infer action distributions by minimizing expected free energy (planning).

This architecture resembles variational autoencoders and model-based RL, but with crucial differences:

- The objective is expected free energy, not reconstruction loss plus KL divergence or expected reward.

- The agent learns to minimize surprise (variational free energy during inference) and expected surprise (expected free energy during planning).

- Epistemic value (information gain) is intrinsic, not bolted on.

Deep active inference combines the inductive biases of the theory (minimize surprise, maintain coherent world models) with the flexibility of deep learning (learn representations from data).

Results are promising: agents that learn visual navigation from pixels, manipulate objects from raw sensory input, and adapt to distribution shifts without catastrophic forgetting. They're not yet state-of-the-art on standard benchmarks (deep RL is highly optimized for those). But they're more sample-efficient, more robust to novel perturbations, and more interpretable—you can inspect the generative model, see what the agent believes, understand why it acts.

What Makes Implementation Hard (And Interesting)

Despite progress, implementing active inference agents remains non-trivial:

Scaling to high-dimensional observations: Discrete models work for small state spaces. Continuous models require approximations (Gaussian assumptions, variational inference, sampling). Scaling to images, lidar, or multimodal inputs demands deep architectures, but maintaining theoretical guarantees becomes difficult.

Specifying preferred observations: In reward maximization, you specify rewards. In active inference, you specify preferred observations or goal states. But how? If you get this wrong, the agent minimizes surprise in ways you didn't intend—like avoiding informative but initially unpredictable situations.

Computational cost of planning: Computing expected free energy for all possible policies is expensive. Tractable implementations use restricted policy classes (short horizons, small action sets) or approximate inference (sampling, amortized inference via networks). Scaling to long-horizon, continuous action spaces remains challenging.

Learning the generative model structure: Most implementations assume a fixed model structure (state space size, model architecture). Learning the structure itself—discovering latent variables, inferring causal relationships—is an open problem. Some approaches use structure learning from data, but this adds complexity.

Bridging discrete and continuous time: The theory is often formulated in continuous time (differential equations, Langevin dynamics). Implementations use discrete time steps. Matching the two isn't always straightforward, especially for continuous control.

These aren't fatal flaws. They're engineering frontiers. And they're being actively addressed.

Why This Matters Beyond Robotics

Active inference is often framed as a framework for embodied agents—robots, organisms, systems that act in physical environments. But the principles apply more broadly:

Language models as active inference agents: A language model minimizes surprise about text by predicting next tokens. Could we recast this as active inference over linguistic observations? Could we make models that actively sample informative prompts (epistemic exploration) rather than passively responding?

Software agents in digital environments: Code generation, debugging, system administration—tasks where agents manipulate symbolic environments. Active inference provides a principled way to balance exploration (trying new commands, discovering system states) with exploitation (achieving goals efficiently).

Multi-agent coordination: Active inference agents that model other agents' beliefs can coordinate without explicit communication. They infer what others know and what others expect them to do. This has applications in human-AI collaboration, swarm robotics, and decentralized systems.

Explainability and interpretability: Unlike black-box deep RL agents, active inference agents have explicit generative models. You can query what they believe, visualize their uncertainty, trace their planning. This matters for safety-critical applications, clinical decision support, and trust in autonomous systems.

Computational psychiatry and neurodiversity: If psychiatric conditions involve atypical inference (unusual precision, biased priors, impaired model updating), then active inference models can simulate these conditions, predict symptoms, and suggest interventions. This isn't just theory—it's being tested clinically.

The implementation revolution makes these applications feasible, not just conceptually possible.

The Convergence with Other Frameworks

Active inference doesn't exist in isolation. It's converging with other approaches:

Model-based reinforcement learning: Both build world models and use them for planning. The difference: active inference minimizes expected free energy (surprise + goal divergence); model-based RL maximizes expected reward. But the architectures overlap. Hybrid approaches are emerging.

Predictive coding: A related theory where neural networks minimize prediction error via bidirectional message passing. Active inference can be seen as predictive coding extended to action. Implementations increasingly integrate both.

Bayesian deep learning: Active inference is fundamentally Bayesian (maintain beliefs over states, actions, models). Bayesian deep learning provides tools for uncertainty quantification in neural networks. Combining the two yields agents that know what they don't know.

World models and Transformers: Large-scale models that predict environment dynamics. Active inference provides a principled way to use world models for planning—compute expected free energy under the model, infer optimal policies.

This convergence suggests that active inference principles—minimize surprise, maintain generative models, use inference for planning—are being rediscovered independently in AI engineering. The theory formalizes what works.

What's Next: The Implementation Frontier

The next wave of active inference implementations will likely involve:

Hierarchical generative models: Multi-scale models where higher levels set priors for lower levels. This enables abstraction, long-term planning, and transfer learning. Implementations are emerging but still rare.

Structure learning: Agents that discover latent variables, infer causal graphs, and revise their generative model architecture based on experience. This moves beyond parameter learning to model discovery.

Continual learning: Active inference agents should naturally avoid catastrophic forgetting—new experiences update beliefs without erasing old knowledge. Implementing this robustly remains challenging.

Integration with symbolic reasoning: Combine probabilistic generative models with logic, rules, and compositional structure. Active inference over structured knowledge graphs, not just continuous latent spaces.

Hardware acceleration: Neuromorphic chips, probabilistic computing, analog inference. Active inference maps naturally to certain hardware architectures. Implementations that exploit this could be orders of magnitude more efficient.

Real-world deployments: Moving beyond simulations to physical robots, clinical tools, deployed assistants. This requires robustness, safety guarantees, and failure modes that degrade gracefully.

The mathematical theory is mature. The implementation tooling is functional. The research community is growing. What's needed now: engineers building, testing, breaking, and improving active inference systems in the wild.

Why You Should Care

If you're building AI agents, consider this:

Active inference changes the framing. Instead of asking "what reward function captures my objective?" you ask "what generative model describes this environment?" Instead of tuning exploration bonuses, you let epistemic value emerge from expected free energy. Instead of black-box policies, you get interpretable models.

The math is real. This isn't hand-waving about "how the brain works." It's rigorous information theory, variational inference, and probabilistic modeling. The implementations prove it computes.

The community is open. Frameworks are open-source. Papers include code. Researchers answer questions on GitHub and forums. This is a field you can enter, contribute to, and shape.

The problems are hard and interesting. Scaling to high-dimensional observations, learning model structure, balancing exploration and exploitation—these aren't solved. They're active research. Your contribution could matter.

And if you're not building agents but thinking about intelligence, agency, or meaning: active inference offers a coherence-based account of agency. Agents persist by maintaining coherence between their models and their environments. They act to minimize surprise—to stay within states they expect. Goals aren't external rewards but expected observations encoded in the generative model.

In AToM terms: M = C/T. Meaning (agency, goal-directed behavior) equals coherence (aligned model and environment) over time. Active inference formalizes this. Implementations make it real.

This is Part 1 of the Active Inference Applied series, exploring how active inference moves from theoretical neuroscience into working code—agents, robots, systems that learn by minimizing surprise.

Next: The Generative Model: Building World Models for Active Inference Agents

Further Reading

- Friston, K. (2010). "The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?" Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

- Da Costa, L., Parr, T., Sajid, N., Veselic, S., Neacsu, V., & Friston, K. (2020). "Active inference on discrete state-spaces: A synthesis." Journal of Mathematical Psychology.

- Heins, C., et al. (2022). "pymdp: A Python library for active inference in discrete state spaces." Journal of Open Source Software.

- Çatal, O., Verbelen, T., Van de Maele, T., Dhoedt, B., & Safron, A. (2021). "Robot navigation as hierarchical active inference." Neural Networks.

- Friston, K., Da Costa, L., Hafner, D., Hesp, C., & Parr, T. (2021). "Sophisticated inference." Neural Computation.

- Millidge, B., Tschantz, A., & Buckley, C. L. (2021). "Whence the expected free energy?" Neural Computation.

Comments ()