Functions: The Input-Output Machines of Mathematics

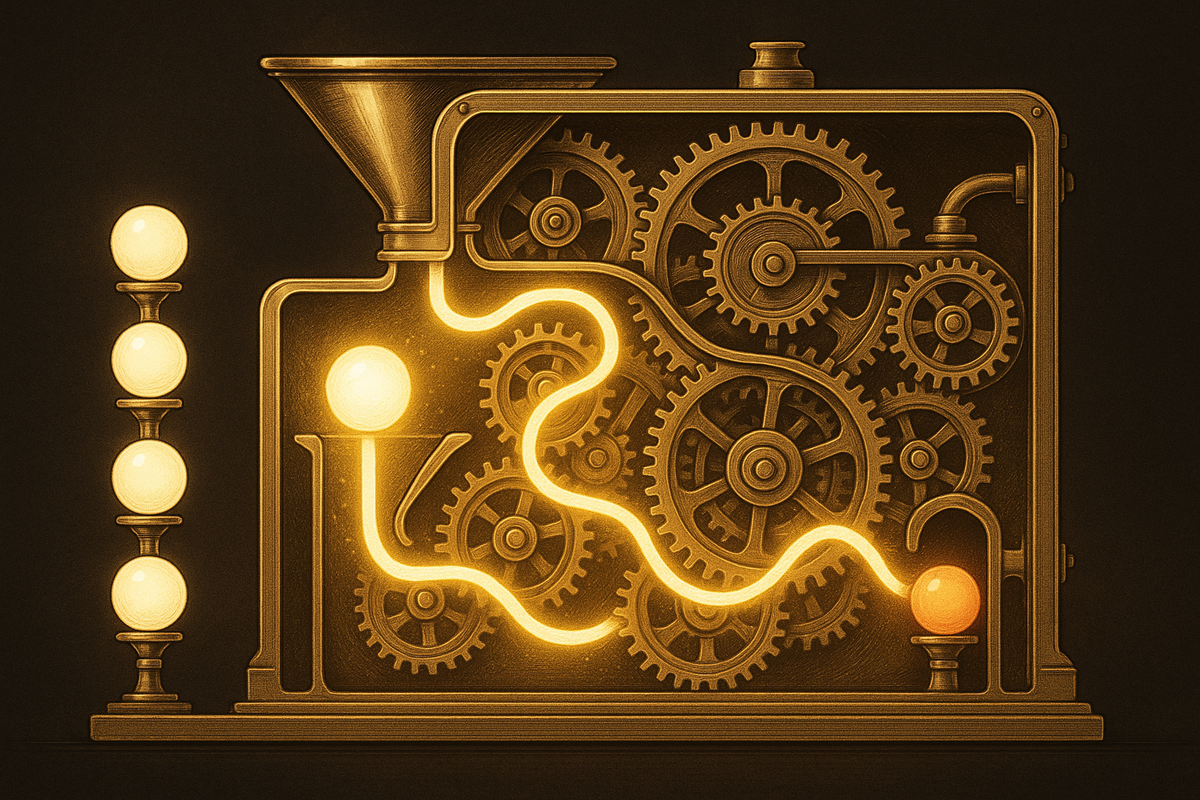

A function is a machine: one input in, one output out.

You feed it a number. It does something to that number. It spits out exactly one result. Same input always produces same output.

Here's the unlock: a function is not a formula. A formula is one way to describe a function, but the function itself is the relationship — the rule that pairs each input with exactly one output. Tables, graphs, formulas, and verbal descriptions can all define the same function.

Once you see functions as input-output pairings rather than formulas to memorize, they become intuitive.

The Definition

A function is a rule that assigns exactly one output to each input.

Input → Function → Output x → f → f(x)

The notation f(x) means "the output of function f when the input is x."

f(x) = 2x + 3

This says: "Whatever you put in, double it and add 3."

f(1) = 2(1) + 3 = 5 f(4) = 2(4) + 3 = 11 f(-2) = 2(-2) + 3 = -1

Why "Exactly One Output"?

The key word is exactly one.

✓ Function: Each student has exactly one student ID number. ✗ Not a function: Each person has exactly one phone number. (Some people have multiple.)

If an input could produce two different outputs, you wouldn't have a function. Functions are deterministic — same input, same output, every time.

Domain and Range

Domain: All possible inputs (what you can feed the machine).

Range: All possible outputs (what the machine can produce).

For f(x) = √x:

- Domain: x ≥ 0 (can't take square root of negative)

- Range: f(x) ≥ 0 (square roots are non-negative)

For f(x) = 1/x:

- Domain: x ≠ 0 (can't divide by zero)

- Range: f(x) ≠ 0 (output is never zero)

The domain is where the function "lives." The range is where it "reaches."

Function Notation

f(x) is read "f of x" — it means "apply function f to input x."

The letter f is just a name. Functions can be g(x), h(t), P(n), whatever.

f(x) = x² defines a squaring function.

- f(3) = 9

- f(-2) = 4

- f(a + b) = (a + b)²

The parentheses don't mean multiplication. They mean "function applied to."

Evaluating Functions

To evaluate f(x) at a specific value, substitute that value for x.

f(x) = 3x² - 2x + 1

f(2) = 3(2)² - 2(2) + 1 = 12 - 4 + 1 = 9 f(-1) = 3(-1)² - 2(-1) + 1 = 3 + 2 + 1 = 6 f(0) = 3(0)² - 2(0) + 1 = 1

The x is a placeholder. Replace it with whatever you're given.

The Vertical Line Test

How do you know if a graph represents a function?

Vertical line test: If any vertical line crosses the graph more than once, it's not a function.

Why? A vertical line represents all points with one x-value. If it crosses twice, that input has two outputs — violating the definition.

- Parabola y = x²: passes (each vertical line hits once)

- Circle x² + y² = 1: fails (most vertical lines hit twice)

Circles aren't functions. Each x-value has two y-values.

Common Function Types

Linear: f(x) = mx + b (straight line) Quadratic: f(x) = ax² + bx + c (parabola) Polynomial: f(x) = aₙxⁿ + ... + a₁x + a₀ Rational: f(x) = p(x)/q(x) (ratio of polynomials) Exponential: f(x) = aˣ (constant base, variable exponent) Logarithmic: f(x) = logₐ(x) (inverse of exponential) Trigonometric: f(x) = sin(x), cos(x), tan(x)

Each type has characteristic shapes and behaviors.

Combining Functions

Functions can be combined like numbers:

(f + g)(x) = f(x) + g(x) — add the outputs

(f · g)(x) = f(x) · g(x) — multiply the outputs

(f/g)(x) = f(x)/g(x) — divide the outputs (where g(x) ≠ 0)

Example: f(x) = x², g(x) = x + 1

(f + g)(x) = x² + x + 1 (f · g)(x) = x²(x + 1) = x³ + x²

Composition: Functions of Functions

(f ∘ g)(x) = f(g(x)) — apply g first, then f to the result.

This is "function composition" — chaining machines.

f(x) = x², g(x) = x + 3

(f ∘ g)(x) = f(g(x)) = f(x + 3) = (x + 3)² (g ∘ f)(x) = g(f(x)) = g(x²) = x² + 3

Note: f ∘ g ≠ g ∘ f in general. Order matters.

Inverse Functions

If f turns a into b, the inverse function f⁻¹ turns b back into a.

f(x) = 2x (double the input) f⁻¹(x) = x/2 (halve the input — undoes doubling)

Check: f(f⁻¹(x)) = f(x/2) = 2(x/2) = x ✓

The inverse undoes what the original function did.

Not all functions have inverses. For f⁻¹ to exist, f must be one-to-one: different inputs give different outputs. Otherwise, you can't uniquely reverse.

Finding Inverse Functions

To find f⁻¹:

- Write y = f(x)

- Swap x and y

- Solve for y

Example: f(x) = 2x + 3

y = 2x + 3 x = 2y + 3 (swap) x - 3 = 2y y = (x - 3)/2

So f⁻¹(x) = (x - 3)/2

Graphing Functions

A function's graph shows all input-output pairs as points (x, f(x)).

- Intercepts: Where the graph crosses the axes

- y-intercept: f(0)

- x-intercepts: values where f(x) = 0

- Increasing/decreasing: Where the function goes up or down

- Maximum/minimum: Highest and lowest points

The graph is a visual representation of the entire function at once.

Piecewise Functions

Some functions have different rules for different inputs:

f(x) = { x², if x < 0 { 2x, if x ≥ 0

For negative inputs, square. For non-negative, double.

f(-3) = (-3)² = 9 f(4) = 2(4) = 8

The function is defined "in pieces" over different domains.

Why Functions Matter

Functions are the central object of mathematics.

Calculus studies how functions change (derivatives) and accumulate (integrals).

Physics describes nature with functions: position as a function of time, force as a function of distance.

Computer science is built on functions: programs are functions that transform inputs to outputs.

Whenever you have a consistent relationship between quantities — when knowing one determines the other — you have a function.

The Core Insight

A function is a consistent pairing: each input maps to exactly one output.

Not a formula (that's one representation). Not a graph (that's another representation). The function is the relationship itself — the rule that connects inputs to outputs.

The formula, the table, the graph, and the verbal description are all windows onto the same underlying object. Master functions, and you've mastered the language that mathematics, science, and computing all speak.

Part 10 of the Algebra Fundamentals series.

Previous: Polynomials: Expressions with Multiple Powers of x Next: Graphing: Making Equations Visible

Comments ()