Greatest Common Divisor: What Numbers Share

The GCD is the largest number that divides both.

gcd(12, 18) = 6. Both 12 and 18 are divisible by 6, and no larger number divides both.

gcd(35, 49) = 7. Both are divisible by 7, but not by any larger common factor.

gcd(8, 15) = 1. They share no common factor except 1 — they're coprime.

The GCD captures what two numbers have in common, multiplicatively.

That's the unlock. When you reduce a fraction to lowest terms, you divide by the GCD. When you find a common rhythm between two cycles, you're finding their GCD. The greatest common divisor tells you the largest "unit" that measures both numbers evenly.

The Definition

The greatest common divisor of a and b, written gcd(a, b), is the largest positive integer that divides both a and b.

Equivalently: gcd(a, b) is the largest d such that d | a and d | b.

Finding GCD by Factorization

Factor both numbers. Take the minimum power of each common prime.

gcd(360, 150): 360 = 2³ × 3² × 5 150 = 2 × 3 × 5²

Common primes: 2, 3, 5 Minimum powers: 2¹, 3¹, 5¹

gcd(360, 150) = 2 × 3 × 5 = 30

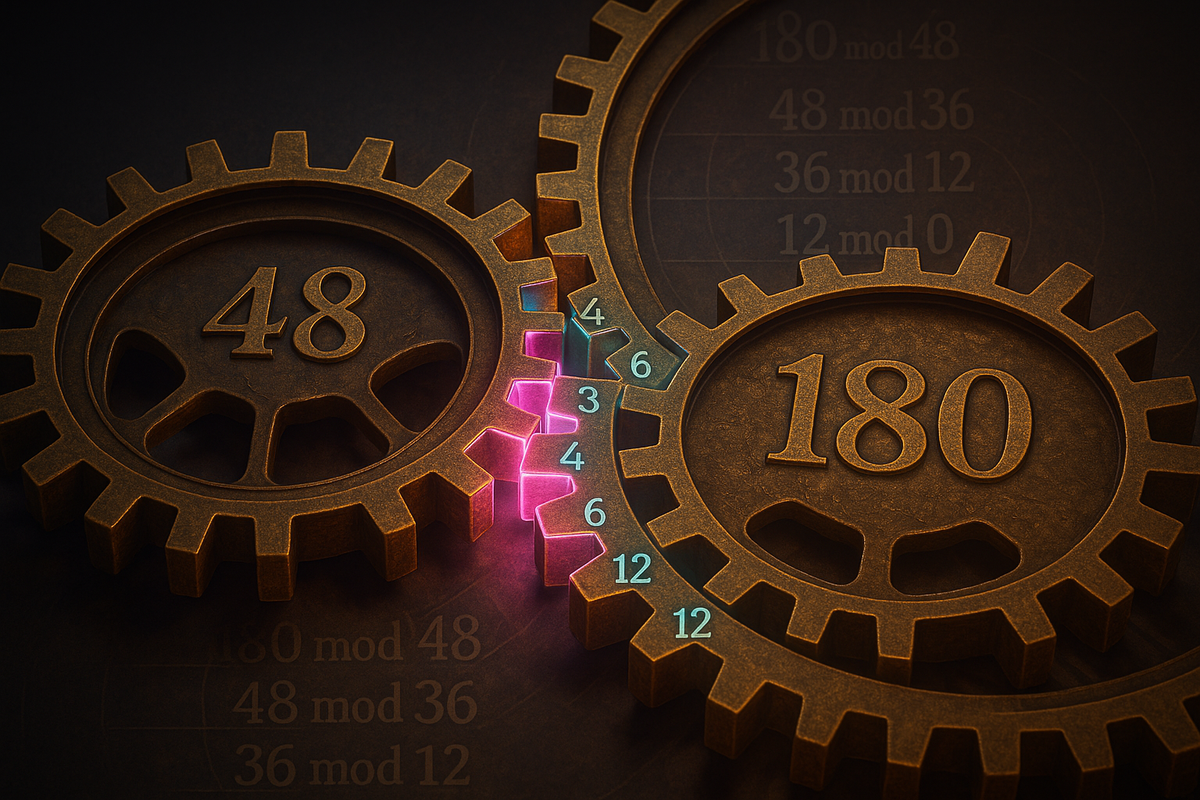

Euclid's Algorithm

Factoring is slow for large numbers. Euclid's algorithm is fast.

Key insight: gcd(a, b) = gcd(b, a mod b)

The GCD of two numbers equals the GCD of the smaller and the remainder.

Example: gcd(252, 105)

252 = 2 × 105 + 42 → gcd(252, 105) = gcd(105, 42) 105 = 2 × 42 + 21 → gcd(105, 42) = gcd(42, 21) 42 = 2 × 21 + 0 → gcd(42, 21) = gcd(21, 0) = 21

gcd(252, 105) = 21

When the remainder hits 0, the last nonzero remainder is the GCD.

Why Euclid's Algorithm Works

If d | a and d | b, then d | (a - qb) for any integer q.

In particular, d | (a mod b).

So any common divisor of a and b is also a common divisor of b and (a mod b).

The GCDs are equal. Keep reducing until one number is 0.

gcd(a, 0) = a (everything divides 0).

Properties of GCD

Commutative: gcd(a, b) = gcd(b, a)

gcd(a, 0) = a: The GCD with zero is the other number.

gcd(a, a) = a: A number's GCD with itself is itself.

gcd(a, 1) = 1: 1 is the only divisor of 1.

Associative: gcd(a, gcd(b, c)) = gcd(gcd(a, b), c)

Coprime Numbers

a and b are coprime (or relatively prime) if gcd(a, b) = 1.

They share no common factor except 1.

Examples:

- gcd(8, 15) = 1 (coprime)

- gcd(14, 15) = 1 (coprime, even though consecutive)

- gcd(12, 18) = 6 ≠ 1 (not coprime)

Coprime doesn't mean prime. 8 and 15 are both composite, yet coprime.

Bézout's Identity

For any integers a and b, there exist integers x and y such that:

ax + by = gcd(a, b)

This is remarkable. The GCD can always be expressed as a linear combination of a and b.

Example: gcd(252, 105) = 21

From Euclid's algorithm: 21 = 105 - 2(42) = 105 - 2(252 - 2×105) = 5(105) - 2(252)

So 21 = 5(105) + (-2)(252). We have x = -2, y = 5.

The Extended Euclidean Algorithm

Runs Euclid's algorithm while tracking how to express the GCD as a linear combination.

This is crucial for:

- Finding modular inverses

- Solving linear Diophantine equations

- Cryptographic computations

GCD and Fractions

To reduce a/b to lowest terms, divide both by gcd(a, b).

18/24: gcd(18, 24) = 6. 18/24 = (18÷6)/(24÷6) = 3/4.

A fraction is in lowest terms iff gcd(numerator, denominator) = 1.

GCD and LCM Relationship

gcd(a, b) × lcm(a, b) = a × b

If you know one, you can find the other: lcm(a, b) = (a × b) / gcd(a, b)

Example: gcd(12, 18) = 6 lcm(12, 18) = (12 × 18) / 6 = 216 / 6 = 36

Multiple Numbers

gcd(a, b, c) = gcd(gcd(a, b), c)

Compute pairwise and combine.

gcd(12, 18, 30): gcd(12, 18) = 6 gcd(6, 30) = 6

gcd(12, 18, 30) = 6

Applications

Reducing fractions: Divide by GCD.

Cryptography: Finding modular inverses uses the extended Euclidean algorithm.

Music theory: The GCD of two frequencies determines their harmonic relationship.

Tiling: An a × b rectangle can be perfectly tiled by d × d squares iff d | gcd(a, b).

The Core Insight

The GCD extracts the common multiplicative structure of two numbers.

When gcd(a, b) = d, you can write a = d × a' and b = d × b' where gcd(a', b') = 1. The GCD is the "shared part"; what remains after dividing by the GCD is the "individual part."

Euclid's algorithm makes this computable, even for huge numbers. Bézout's identity reveals that the GCD isn't just a divisor — it's the smallest positive number expressible as a linear combination of a and b.

Part 5 of the Number Theory series.

Previous: Divisibility Rules: Patterns in the Digits Next: Least Common Multiple: When Cycles Align

Comments ()