General Relativity: Gravity Is Geometry

Series: Spacetime Physics | Part: 2 of 9 Primary Tag: FRONTIER SCIENCE Keywords: general relativity, Einstein, curved spacetime, gravity, geodesics, gravitational lensing

In 1907, Albert Einstein had what he later called "the happiest thought of my life."

He imagined a person falling freely from a roof. During the fall, the person would be weightless—they wouldn't feel gravity at all. Einstein realized this meant something profound: gravity and acceleration are equivalent. You can't tell the difference between standing on Earth and accelerating through space at 9.8 m/s².

This "equivalence principle" would take eight more years to develop into general relativity—Einstein's theory of gravity that replaced Newton's and reshaped our understanding of space, time, and the cosmos.

The Problem With Newton

Newton's law of universal gravitation worked beautifully for centuries. Every mass attracts every other mass. The force is proportional to both masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance. F = Gm₁m₂/r².

Simple. Elegant. Extremely accurate.

But Newton himself knew something was wrong. Gravity in his theory acted instantaneously across any distance. If the Sun suddenly disappeared, Earth would instantly feel the change in gravitational pull. Information was traveling infinitely fast.

That violated everything special relativity established. Nothing—including information—can travel faster than light.

Newton's gravity also had a conceptual problem: it didn't explain what gravity was. How does the Sun reach across 150 million kilometers of empty space to pull on Earth? Newton famously wrote "I frame no hypotheses"—he could describe gravity mathematically but not explain its mechanism.

Einstein's theory would solve both problems.

Spacetime Curvature

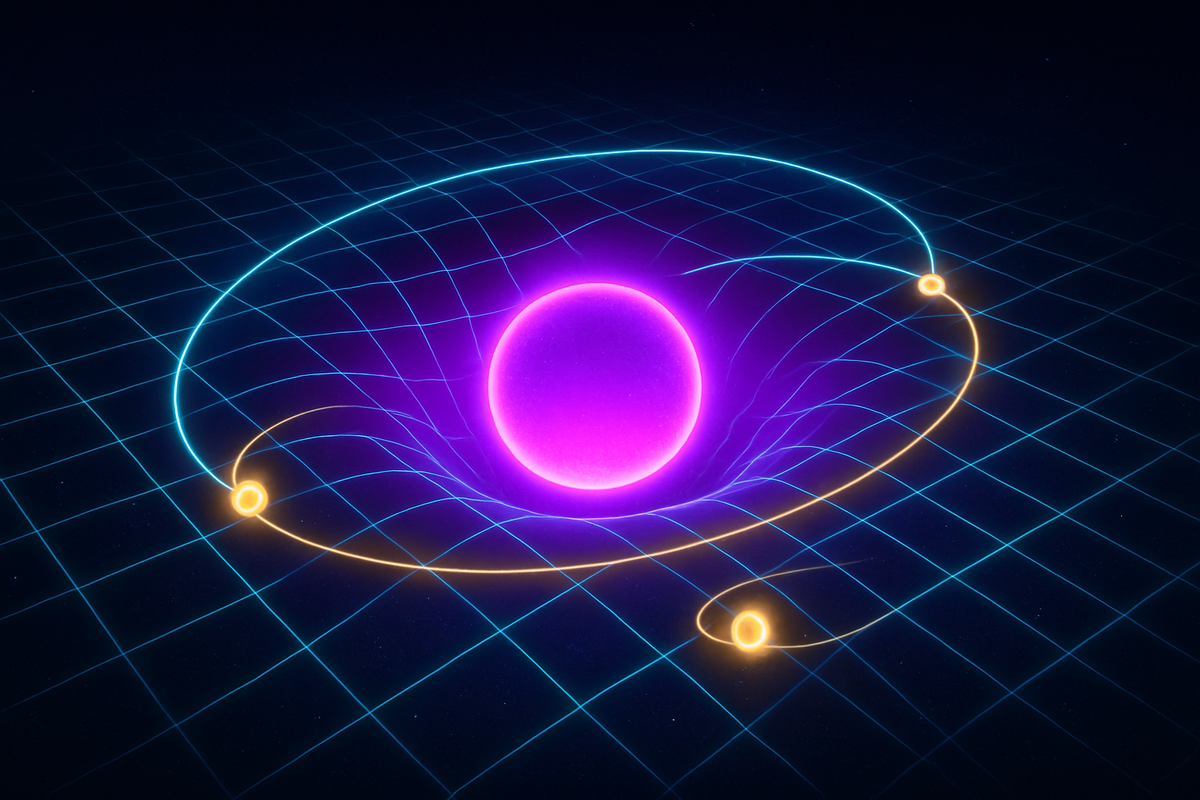

Here's Einstein's insight: gravity isn't a force at all. It's geometry.

Mass and energy curve spacetime. Objects then move along the straightest possible paths through that curved geometry. What we perceive as gravitational attraction is actually objects following the natural contours of warped spacetime.

The famous rubber sheet analogy helps (though it's imperfect): imagine a stretched rubber sheet. Place a bowling ball on it—the sheet curves. Roll a marble nearby—it spirals toward the bowling ball, not because the bowling ball pulls it, but because the marble is following the curved surface.

The Einstein Field Equations express this mathematically:

Gμν = 8πG/c⁴ × Tμν

The left side describes spacetime curvature. The right side describes the distribution of mass-energy. They're equal: mass tells spacetime how to curve, and curved spacetime tells mass how to move.

John Wheeler summarized it: "Spacetime tells matter how to move; matter tells spacetime how to curve."

Geodesics: The Straightest Path

In flat space, the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Objects in motion continue in straight lines unless acted upon (Newton's first law).

In curved space, the shortest distance is called a geodesic. It's not a straight line in the usual sense—it curves—but it's the straightest possible path given the geometry.

On Earth's surface, geodesics are great circles. An airplane flying from New York to Tokyo takes a curved path on a flat map, but it's actually flying the shortest route—the geodesic on Earth's curved surface.

Similarly, planets orbit the Sun not because the Sun pulls them with a force, but because they're following geodesics in the curved spacetime around the Sun. The elliptical orbit IS the straight-line path through that geometry.

A falling apple doesn't accelerate because Earth exerts a force on it. It follows a geodesic—a straight path through curved spacetime—while Earth's surface accelerates upward to meet it.

This is why Einstein called his realization about free fall his "happiest thought." The falling person isn't experiencing a force—they're simply moving along the natural paths of spacetime. It's the person standing on the ground who's being accelerated (by the ground pushing up against them).

Time Curvature

Spacetime curvature affects time as well as space—and for most everyday situations, the time effect dominates.

Near a massive object, time runs slower. A clock on the ground floor of a building ticks slightly slower than a clock on the top floor. A clock on Earth's surface ticks slower than a clock on a satellite.

This is gravitational time dilation, distinct from the velocity-based time dilation of special relativity. (GPS satellites experience both and must account for both.)

The effect is tiny at Earth's surface—clocks at sea level run about 1 second slow per every 300 million years compared to clocks infinitely far from Earth. But near more massive objects, the effect grows dramatic. At the event horizon of a black hole, time stops altogether from an outside observer's perspective.

This time curvature is actually the dominant component of what we call gravity in everyday situations. When you stand on Earth, you're being pushed by the ground against the gradient of curved time. The "force" you feel is mostly the time component of spacetime curvature.

Predictions and Confirmations

General relativity made specific predictions different from Newton's:

Mercury's orbit: Mercury's orbit precesses—the ellipse itself rotates slowly. Newton's theory predicted precession from other planets' influence, but the observed value was off by 43 arcseconds per century. General relativity predicted exactly that discrepancy. Einstein later said this discovery gave him heart palpitations.

Light bending: Light should bend around massive objects because light follows geodesics in curved spacetime. The famous 1919 eclipse expedition led by Arthur Eddington confirmed that stars near the Sun's edge appeared shifted by the amount Einstein predicted—twice what Newton's theory (treating light as particles with mass) would predict.

Gravitational redshift: Light climbing out of a gravity well loses energy and shifts toward red wavelengths. Measured first in 1959 using the Mössbauer effect, later confirmed to high precision using atomic clocks at different altitudes.

Gravitational time dilation: Clocks run slower in stronger gravitational fields. Confirmed with atomic clocks on aircraft (Hafele-Keating experiment, 1971) and by GPS satellite operations (continuously).

Gravitational waves: Accelerating masses should emit waves in spacetime itself, traveling at the speed of light. Indirectly confirmed through the orbital decay of binary pulsars (Hulse-Taylor, 1974). Directly detected by LIGO in 2015—the merger of two black holes rippled spacetime enough for us to measure.

Black holes: Regions where spacetime curves so severely that nothing can escape. Predicted mathematically in 1916, observed indirectly for decades, directly imaged in 2019 (Event Horizon Telescope).

The Elegant Horror

General relativity is mathematically beautiful and conceptually disturbing.

It's beautiful because geometry replaces force. The same mathematical framework describes planetary orbits, light bending, gravitational waves, black holes, and the expansion of the universe. Everything is spacetime curvature.

It's disturbing because it undermines intuitions we didn't even know we had. There's no absolute space. There's no absolute time. There's no universal "now." Simultaneity is relative. The geometry of the universe depends on what's in it.

And it gets worse. The theory allows solutions that seem physically absurd—closed timelike curves (time travel), wormholes, naked singularities. Whether these are physical possibilities or mathematical artifacts is still debated.

General relativity also breaks down in its own predictions. At black hole singularities and the Big Bang, the curvature becomes infinite. The theory predicts its own failure at these points—a sign that quantum effects must become important where we don't yet know how to include them.

What General Relativity Changed

Before Einstein, space and time were the stage on which physics happened. After Einstein, space and time are part of the physics—dynamic, responsive, participant.

This shift transformed cosmology. The universe can expand (and does). The Big Bang is a prediction of general relativity—run the expansion backward, and everything converges to a singularity.

It transformed astrophysics. Black holes, neutron stars, gravitational waves—all general relativistic phenomena. We now detect black hole mergers from billions of light-years away by the ripples they send through spacetime.

It raised profound questions. If spacetime curvature is gravity, and quantum mechanics describes everything else, what is quantum gravity? How does spacetime itself behave at quantum scales? We don't know. That's the unfinished revolution we'll discuss later in this series.

The Takeaway

Gravity is not a force pulling you down. It's the shape of spacetime pushing you up.

When you stand on Earth, you're being accelerated upward by the ground. When you fall, you're following the natural contours of curved spacetime—weightless, in free fall, taking the straightest possible path through geometry warped by Earth's mass.

Everything with mass curves spacetime. The effect is usually tiny—you slightly curve the space around you right now—but accumulate enough mass and the curvature becomes extreme: white dwarfs, neutron stars, black holes.

Time and space aren't separate; they're aspects of spacetime. Spacetime isn't fixed; it responds to what's in it. What we call gravity is how we experience that response.

It took Einstein eight years to figure this out. It will take the rest of physics centuries to fully understand what it means.

Further Reading

- Einstein, A. (1915). "The Field Equations of Gravitation." Prussian Academy of Sciences. - Wheeler, J.A. & Ford, K.W. (2000). Geons, Black Holes, and Quantum Foam. W.W. Norton. - Carroll, S. (2003). Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity. Addison-Wesley.

This is Part 2 of the Spacetime Physics series. Next: "Black Holes: Where Spacetime Breaks."

Comments ()