Genetic Circuits: Cells as Computers

In 2000, two papers published in the same issue of Nature launched a new field.

One described a "toggle switch"—a genetic circuit with two stable states, like a light switch that stays on or off. The other described a "repressilator"—a circuit that oscillates rhythmically, like a biological clock.

These weren't natural circuits discovered in cells. They were synthetic—designed from scratch, built from characterized parts, and inserted into bacteria to see if they'd work.

They worked.

The toggle switch could be flipped between states with chemical signals. The repressilator oscillated with a predictable period. The bacteria had been programmed.

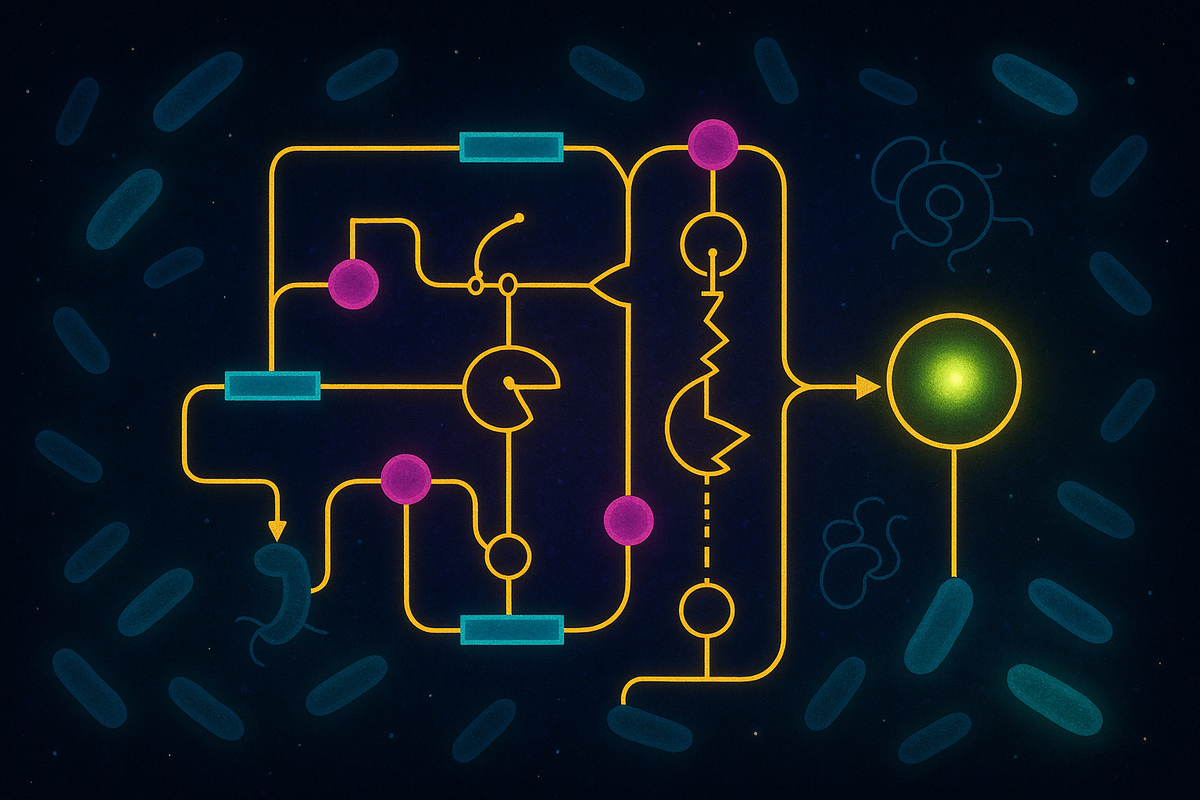

This was the beginning of synthetic genetic circuits—using DNA, RNA, and proteins as components to build computational systems inside living cells. The cell becomes a computer. The genome becomes the program.

Biology already computes. Now we're learning to write our own programs.

What Is a Genetic Circuit?

A genetic circuit is a system of interacting genes that processes information.

The components are biological: - Promoters: DNA sequences where transcription starts. They can be regulated—turned on or off by signals. - Repressors: Proteins that bind to promoters and prevent transcription. - Activators: Proteins that bind to promoters and enhance transcription. - Reporters: Proteins that produce a readable output—fluorescence, for example.

The logic is computational: - If protein A is present, gene B is off. - If chemical C is present, protein A can't bind, so gene B turns on. - This is an AND gate, an OR gate, a NOT gate—the building blocks of digital logic.

Natural cells are full of genetic circuits. The lac operon in E. coli—the textbook example of gene regulation—is a circuit that turns on lactose metabolism genes only when lactose is present and glucose is absent. Evolution built it. We study it.

Synthetic biology asks: can we build our own?

The Foundational Circuits

The toggle switch (Gardner et al., 2000) has two repressors that inhibit each other. Repressor A blocks the gene for Repressor B; Repressor B blocks the gene for Repressor A.

This creates bistability—two stable states. In one state, A is high and B is low. In the other, B is high and A is low. The system stays in whichever state it's in until pushed.

A pulse of inducer (a chemical that inhibits one repressor) can flip the switch. Remove the inducer, and the switch stays in its new state. It has memory—a one-bit latch.

The repressilator (Elowitz & Leibler, 2000) has three repressors arranged in a cycle. A represses B, B represses C, C represses A.

This creates oscillation. When A is high, it suppresses B. But then A decreases (proteins degrade), B increases, B suppresses C, C decreases, A increases again. The cycle repeats. The period is determined by the degradation rates and other parameters.

The bacteria hosting the repressilator flash rhythmically—a green fluorescent protein reporter glows on and off as the circuit cycles.

These circuits are simple. They're also foundational. Toggle switches and oscillators are building blocks for more complex systems.

Logic Gates in Cells

Digital computers use logic gates: AND, OR, NOT, XOR, etc. Can cells do the same?

Yes, with caveats.

NOT gate: Gene A produces a repressor that blocks Gene B. When A is on, B is off; when A is off, B is on. Inversion.

AND gate: Gene C is only transcribed when both Signal X AND Signal Y are present. You can build this with a promoter that requires two activators.

OR gate: Gene D is transcribed when Signal X OR Signal Y is present. A promoter with two alternative binding sites can do this.

More complex gates—NAND, NOR, XOR—can be constructed by combining simpler elements.

In 2011, Chris Voigt's lab demonstrated a library of logic gates in bacteria, including a system that could be wired together to perform arbitrary Boolean computations. The cells evaluated multi-input logic functions and produced fluorescent outputs.

Cells can compute. The computation is slow (minutes to hours per operation) but real.

Sensors and Actuators

Circuits need inputs and outputs.

Biosensors are circuits that detect environmental signals. Bacteria can be engineered to respond to: - Specific chemicals (arsenic, TNT, pollutants) - Light (optogenetics) - Temperature - pH - Other cells (quorum sensing)

The sensor converts an external signal into a change in gene expression. That change can then be processed by downstream circuits.

Actuators are circuits that produce useful outputs: - Fluorescence (for detection) - Enzymes (for metabolic production) - Cell death (for self-destruction) - Movement (in motile organisms) - Secreted molecules (for communication or therapy)

A complete system: sensor detects condition → circuit processes information → actuator responds. This is the architecture of a biological device.

Design Tools

Building genetic circuits requires design tools—software that helps predict how circuits will behave.

Cello (developed at MIT) is essentially a compiler for genetic circuits. You specify the logic function you want (in a hardware description language). Cello converts it to a DNA sequence—choosing promoters, repressors, and other parts from a characterized library. You synthesize the DNA and put it in cells.

The system isn't perfect—biological parts don't always behave as predicted. But it represents a step toward the engineering ideal: specify what you want, get a design.

Other tools include: - SBOL (Synthetic Biology Open Language): A standard for describing genetic designs - iBioSim and GEC: Simulation tools for predicting circuit dynamics - Benchling and SnapGene: Design and management platforms

The toolchain is maturing. Design is becoming more systematic.

The Challenges

Genetic circuits face fundamental challenges that electronic circuits don't.

Noise. Gene expression is stochastic. A promoter doesn't produce exactly the same amount of protein every time. Small numbers of molecules fluctuate. This noise can cause circuits to behave unpredictably.

Context-dependence. A part that works in one circuit may not work in another. The cellular environment matters. Copy number, growth phase, metabolic load—all affect behavior.

Crosstalk. Repressors and activators can interfere with each other. A circuit designed in isolation may behave differently when combined with other circuits.

Burden. Expressing foreign genes consumes cellular resources—ribosomes, amino acids, ATP. Heavy expression can slow growth or kill cells. The circuit becomes a metabolic load.

Evolution. Cells evolve. If a circuit imposes a fitness cost, mutations that disable it will spread. Engineered circuits are selected against. Keeping them functional over many generations is hard.

These challenges aren't just engineering problems—they're fundamental to biology. Cells aren't blank computing substrates; they're living systems with their own dynamics.

Electronic circuits run on inert substrates. Genetic circuits run on living, evolving, resource-limited cells.

Beyond Boolean

The toggle switch and logic gates are digital—discrete states, binary logic. But biology also does analog computation.

Analog circuits process continuous variables. A circuit might produce an output proportional to the log of an input signal—biological sensors often have logarithmic response curves. Or it might implement a ratio, computing the relative concentration of two signals.

Feedback circuits create dynamic behaviors: adaptation (response followed by return to baseline), amplification (small signals become large), filtering (certain frequencies pass, others don't).

Spatial computation happens when circuits operate differently in different parts of a cell or organism. Development uses spatial circuits to create patterns—stripes, gradients, segments.

The natural genetic programs that build organisms from fertilized eggs are computations of staggering sophistication—far beyond anything synthetic biologists have built. We can create simple logic gates. Embryonic development creates complex three-dimensional structures. The gap is vast.

Applications

Where would you use cellular computers?

Diagnostics. Cells that sense disease markers and report. Bacteria engineered to detect cancer biomarkers in the gut, or pathogens in water supplies. The cell is the sensor platform.

Therapeutics. Cells that sense disease conditions and respond. CAR-T cells are a primitive example—immune cells engineered to recognize and kill cancer. More sophisticated versions could include logic: kill only cells with marker A AND marker B, not cells with marker C.

Biomanufacturing control. Metabolic engineering for chemical production benefits from dynamic control. Instead of static expression levels, circuits that sense metabolic state and adjust enzyme levels accordingly. Self-optimizing production.

Environmental monitoring. Biosensors deployed in the environment—detecting pollution, tracking ecosystems, monitoring soil health. Cells as distributed sensor networks.

Research tools. Synthetic circuits as probes of biological systems. Build a circuit, perturb it, learn how cells respond. Construction as a form of understanding.

Whole-Cell Computation

The most ambitious vision: cells as general-purpose computers.

In 2017, researchers demonstrated a "CRISPR-based analog system" that could implement arbitrary linear functions. Cells computed weighted sums of input signals.

In 2019, a different group created cells that could perform neural-network-style computation—implementing trained classifiers that distinguished inputs.

These aren't fast computers. A silicon chip is billions of times faster. But cells have properties computers don't:

Self-replication. Grow a single engineered cell into billions. Manufacturing cost approaches zero.

Environmental interface. Cells naturally sense and respond to their environments. No external sensors needed.

Biocompatibility. Cells can operate inside living organisms—in the gut, in tumors, in tissue.

The niche isn't replacing silicon. It's computing where silicon can't go.

The Coherence of Cellular Logic

Let's connect to the AToM framework.

Natural cells process information to maintain coherence—staying alive, responding to conditions, coordinating behavior. The genetic circuits evolution built serve this maintenance function.

Synthetic circuits repurpose the same components for human goals. But they still operate within the cell's coherence constraints. A circuit that burdens the cell too much breaks coherence—the cell dies or mutates. A circuit that ignores cellular context fails.

Successful genetic circuits work with cellular coherence, not against it. They're symbiotic programs—serving human goals while not disrupting cellular homeostasis.

This is different from electronic computing, where the substrate is inert. In cellular computing, the substrate has its own agenda. Good design respects that.

Further Reading

- Gardner, T. S., Cantor, C. R., & Collins, J. J. (2000). "Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli." Nature. - Elowitz, M. B., & Leibler, S. (2000). "A synthetic oscillatory network of transcriptional regulators." Nature. - Nielsen, A. A. K., et al. (2016). "Genetic circuit design automation." Science. - Brophy, J. A. N., & Voigt, C. A. (2014). "Principles of genetic circuit design." Nature Methods.

This is Part 6 of the Synthetic Biology series. Next: "Living Materials: Self-Healing and Growing."

Comments ()