Mountains, Rivers, and Ports Determined More History Than Ideas

In 1532, Francisco Pizarro captured the Incan emperor Atahualpa with 168 Spanish soldiers. The Inca Empire had millions of subjects and a sophisticated administration. Spain was a small European kingdom an ocean away. How did 168 men conquer an empire?

The standard answer: guns, germs, and steel. But behind that answer lies another: why did Europe have guns and steel while the Inca didn't? Why did Eurasia develop differently from the Americas?

Jared Diamond's answer: geography. The shape of continents, the distribution of domesticable plants and animals, the orientation of landmasses along climate bands—these facts, set millions of years before humans evolved, shaped which civilizations would develop technologies that conquered others.

This is geographic determinism: the claim that physical geography constrains and channels human possibilities more than we like to admit. It's an uncomfortable idea because it suggests that much of history was shaped by factors no one chose—the random distribution of mountains and rivers and species across landmasses. But discomfort isn't a refutation. The question is whether it's true.

The Continental Argument

Diamond's core insight in Guns, Germs, and Steel: Eurasia's east-west axis gave it decisive advantages over the Americas' north-south axis.

Climate bands run east-west. Plants and animals domesticated in one part of Eurasia could spread across thousands of miles at similar latitudes. Wheat from the Fertile Crescent spread to Europe, India, and China. Horses domesticated on the steppes reached everywhere. This diffusion accelerated development everywhere it reached.

The Americas run north-south. Crops domesticated in Mexico couldn't easily spread to Peru—different climates, different growing seasons, different day lengths. The same with animals. Development remained local rather than cumulative across the continent.

Eurasia had more domesticable species. The major domesticated animals—horses, cattle, pigs, sheep, goats—are almost all Eurasian. The Americas had llamas and alpacas in a limited range, and nothing else suitable. No horses meant no cavalry, no plowing, no rapid communication. This wasn't cultural failure; it was biological bad luck.

Dense populations near domesticated animals produced epidemic diseases. Eurasians developed resistance through millennia of exposure. When they arrived in the Americas, their germs killed up to 90% of indigenous populations. Smallpox conquered before soldiers arrived.

This explains Pizarro. Spain didn't conquer the Inca because of superior culture or courage. They conquered because Eurasia's geography had given them a 10,000-year head start in accumulating technologies and immunities.

The implications are uncomfortable. If your ancestors were conquered, it wasn't because they were inferior—it was because their continent's shape gave them fewer domesticable species and less east-west diffusion. If your ancestors conquered others, it wasn't because they were superior—it was because they inherited geographic luck that translated into technological advantage. History's winners won the lottery before the game even started.

The Map as Explanation

Geographic thinking explains patterns that cultural explanations struggle with:

Why is Africa poor? Standard answers invoke colonialism, governance, or culture. Geographic answers add: Africa has few natural harbors, making trade expensive. Its rivers have cataracts that block navigation. Its tropical diseases burden human productivity. Its soils are often poor. None of these are destiny—but all are headwinds that other regions didn't face.

Why did Europe industrialize first? Coal deposits in Britain and Germany. Iron ore nearby. Rivers for transport. Temperate climate allowing year-round labor. These didn't guarantee industrialization—but they made it easier than in places lacking these endowments.

Why is Russia paranoid? The North European Plain offers no natural barriers between Moscow and potential invaders. Russia has been invaded from the west repeatedly—by Napoleon, by Germany twice. Its strategic behavior—buffer states, territorial expansion, fortress mentality—reflects geographic vulnerability, not mere ideology.

Why are island nations different? Britain and Japan could develop without fear of land invasion. This allowed different political development than continental powers facing constant military pressure. Islands can be naval powers; continental states must maintain large armies.

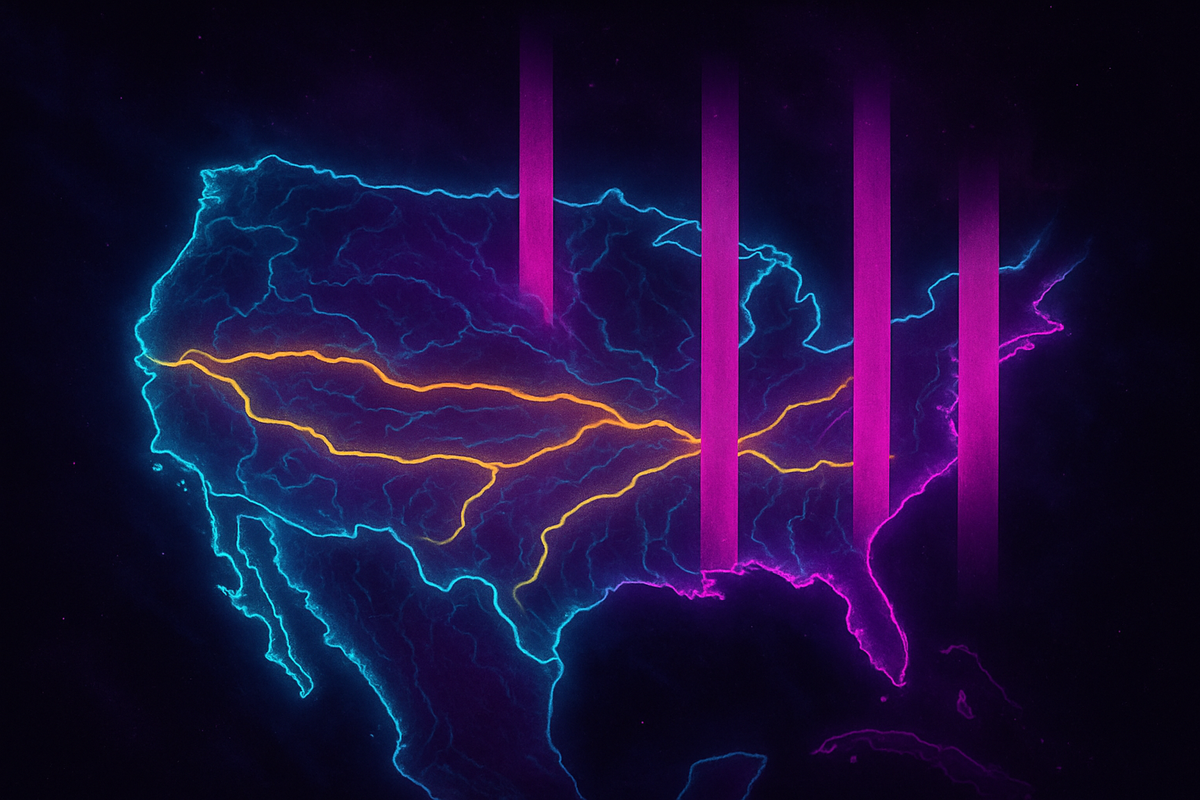

Why did the United States become dominant? Two ocean moats prevent invasion. Friendly or weak neighbors to north and south. The Mississippi River system—the world's largest navigable river network—enables cheap internal transport. Abundant coal, oil, iron, farmland. America's geography is almost absurdly advantageous, and its rise reflects that advantage.

The geographic lens doesn't replace political or cultural analysis. It provides the substrate on which politics operates.

The Limits of Determinism

Geographic determinism has obvious problems:

Geography doesn't change; outcomes do. The Middle East was the cradle of civilization for millennia, then fell behind. China led the world, then stagnated. Britain industrialized; Portugal didn't. Same geography, different trajectories. Geography constrains but doesn't determine.

Human agency matters. The Dutch created land from sea. Singapore became rich despite having nothing but location. Japan industrialized despite lacking coal and iron. Human choices within geographic constraints can produce wildly different outcomes.

Technology changes what geography means. Rivers mattered enormously when water transport was superior. Railroads changed that. Oil was worthless until we needed it. Climate control makes deserts habitable. The significance of geographic features shifts as technology shifts.

Determinism can excuse injustice. If Africa is poor because of geography, does that excuse exploitation? If some peoples were "destined" to be conquered, does that make conquest acceptable? Geographic arguments can slide into apologetics for imperialism.

Culture and institutions clearly matter. North and South Korea have identical geography and wildly different outcomes. West and East Germany diverged for decades under different systems, then converged when reunified. Argentina has excellent geography and persistent underperformance. Geography constrains but doesn't determine.

The sophisticated position isn't that geography determines everything—it's that geography determines more than we usually acknowledge. Culture, institutions, and choices matter enormously. But they operate within constraints that physical reality imposes.

The Geopolitical Tradition

Academic geopolitics emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, attempting to make these geographic constraints explicit:

Friedrich Ratzel coined "Lebensraum"—living space—arguing that states needed territorial expansion to survive. The Nazis weaponized this concept, discrediting it for decades.

Halford Mackinder identified the Eurasian "Heartland" as the pivot of world politics—whoever controlled it could control the "World-Island" of Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Alfred Thayer Mahan argued that sea power determined great-power status—controlling ocean trade routes mattered more than territorial extent.

Nicholas Spykman countered Mackinder: the "Rimland" around Eurasia's coasts mattered more than the Heartland. America should prevent any power from dominating this rim.

These theorists shaped actual policy. The Cold War containment strategy drew on Spykman. NATO exists partly because of Mackinder. The U.S. Navy's global presence reflects Mahan.

Geopolitics fell out of academic fashion after its Nazi associations, but practitioners never stopped thinking geographically. Every war plan, alliance structure, and trade negotiation involves geographic calculation, whether explicit or not.

The tension between Mackinder's land-power thesis and Mahan's sea-power thesis shaped the 20th century. Britain pursued sea control; Germany pursued continental dominance. America, blessed with both oceanic access and continental resources, could pursue both. The debate continues today: is the Indo-Pacific (sea power) or Central Asia (land power) the key to 21st-century dominance?

Modern Geopolitics

Contemporary analysts have revived geographic thinking:

Peter Zeihan argues that American geography is uniquely advantageous—two ocean moats, friendly neighbors, the world's best river system, abundant resources—and that America's withdrawal from global security commitments will cause chaos because no other power has comparable advantages.

Tim Marshall popularized geographic thinking with Prisoners of Geography, showing how maps explain conflicts from Russia-Ukraine to China-Taiwan to the Middle East.

Robert Kaplan traced how geography shaped American identity and how it will shape 21st-century conflicts over water, food, and climate-stressed regions.

George Friedman at Stratfor built geopolitical forecasting on geographic foundations—predicting state behavior from geographic interests rather than ideological statements.

These thinkers vary in rigor and accuracy, but they share a conviction: you can't understand international politics without understanding maps.

What unites modern geopolitical thinkers is methodological: start with the map. Ask what pressures geography creates. Then ask how leaders respond to those pressures. The map doesn't tell you what will happen, but it tells you what must be dealt with.

What Geographic Thinking Offers

Geographic analysis provides several intellectual services:

Long-term perspective. Political leaders come and go. Ideologies rise and fall. Mountains stay where they are. Geographic thinking cuts through the noise of personalities and events to identify structural constraints that persist across administrations and regimes.

Skepticism about intentions. States claim to act on principles. Geographic thinking asks: what do they have to do regardless of principles? Russia will worry about its western border whether led by tsars, communists, or nationalists. China will want Taiwan whether democratic or authoritarian.

Prediction anchored in constraint. You can't predict what leaders will choose, but you can predict what pressures they'll face. Geographic analysis doesn't say what will happen; it says what must be dealt with.

Humility about intervention. Geographic thinking suggests that changing other countries is harder than idealists assume. Afghanistan's geography makes it ungovernable from outside—as empires repeatedly discover. Some problems have geographic roots that political solutions can't fix.

Recognition of structural constraints. Leaders aren't free to do whatever they want. They operate within pressures created by their country's position, resources, and neighbors. Understanding those pressures helps predict behavior better than analyzing personalities or ideologies.

The Takeaway

Geography shapes possibility. The distribution of mountains, rivers, coasts, climates, and resources creates constraints that politics must navigate. This doesn't mean geography determines history—human choice matters enormously—but it means that understanding physical reality is essential for understanding political reality.

The terrain beneath politics explains patterns that purely political analysis misses. Why some regions are rich and others poor. Why some states are paranoid and others confident. Why some conflicts never resolve. Geography doesn't answer every question, but it poses questions that must be answered.

This doesn't mean we should be fatalists. Humans have overcome geographic obstacles repeatedly—the Dutch created land, Singapore turned location into wealth, Israel made deserts bloom. But overcoming geography requires recognizing it first. Ignoring geographic constraints doesn't make them disappear; it just makes failure more likely.

Maps aren't just about where things are. They're about why things happen.

This series explores geopolitical thinking—classical and contemporary, theoretical and practical. The goal isn't to reduce everything to geography, but to add geographic thinking to the analytical toolkit.

The payoff is practical: better predictions, fewer surprises, more realistic expectations. Understanding that Russia will always worry about its western approaches—regardless of who rules—helps interpret its behavior. Recognizing that China needs to secure energy imports helps explain its naval expansion. Seeing that America has unmatched geographic advantages contextualizes its global role. Geographic thinking doesn't predict specific events, but it illuminates the structural pressures that shape events.

Further Reading

- Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel. Norton. - Kaplan, R. D. (2012). The Revenge of Geography. Random House. - Marshall, T. (2015). Prisoners of Geography. Scribner.

This is Part 1 of the Geography of Power series. Next: "Mackinder and Spykman: Heartland Theory"

Comments ()