Geometric Series: Summing Geometric Sequences

Geometric series have a formula. And unlike arithmetic series, they can sum to finite values even when infinite.

Add up 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 + 64.

You could add them one by one. Or you could notice: this equals 2⁷ - 1 = 127.

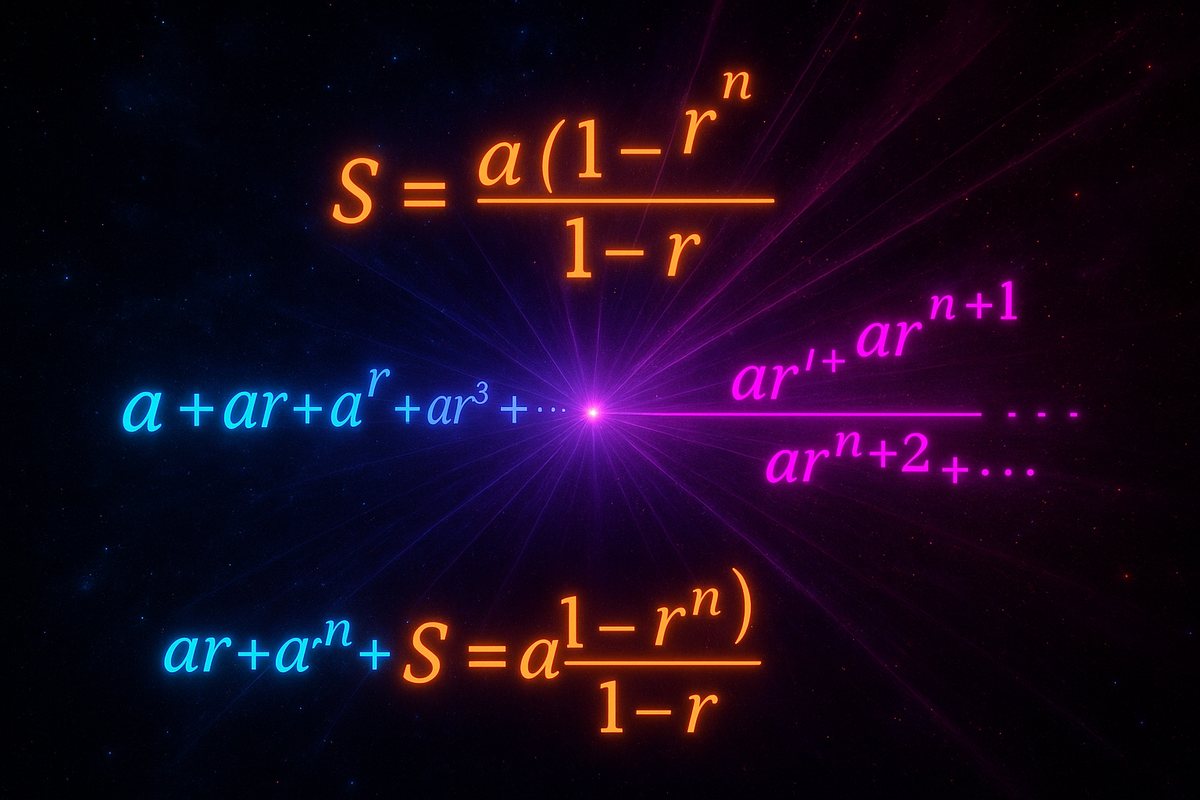

That's not a coincidence. When each term is a fixed multiple of the previous one, the sum has a beautiful closed form:

Sₙ = a₁(1 - rⁿ)/(1 - r), for r ≠ 1

One formula handles any geometric sequence. The magic is in how the terms telescope.

Deriving the Formula

Let Sₙ = a₁ + a₁r + a₁r² + ... + a₁rⁿ⁻¹

Multiply both sides by r: rSₙ = a₁r + a₁r² + a₁r³ + ... + a₁rⁿ

Now subtract: Sₙ - rSₙ = a₁ - a₁rⁿ

Most terms cancel—the sum telescopes.

Sₙ(1 - r) = a₁(1 - rⁿ)

Sₙ = a₁(1 - rⁿ)/(1 - r)

The formula works because multiplying a geometric series by r just shifts it by one position. The difference between Sₙ and rSₙ leaves only the first and last terms standing.

Alternative Forms

Form 1: Sₙ = a₁(1 - rⁿ)/(1 - r)

Use when |r| < 1. The (1 - rⁿ) term approaches 1 as n grows.

Form 2: Sₙ = a₁(rⁿ - 1)/(r - 1)

Same formula, just multiply numerator and denominator by -1. Use when |r| > 1 to avoid negative denominators.

Special case r = 1: Every term equals a₁, so Sₙ = na₁.

The formulas are undefined at r = 1 (division by zero), but the limit works out to na₁.

Examples

Sum of 2 + 6 + 18 + 54 + 162

a₁ = 2, r = 3, n = 5

S₅ = 2(1 - 3⁵)/(1 - 3) = 2(1 - 243)/(-2) = 2(-242)/(-2) = 242

Sum of 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16

a₁ = 1, r = 1/2, n = 5

S₅ = 1(1 - (1/2)⁵)/(1 - 1/2) = (1 - 1/32)/(1/2) = (31/32) × 2 = 31/16

Powers of 2 from 1 to 2¹⁰

1 + 2 + 4 + ... + 1024

a₁ = 1, r = 2, n = 11 (eleven terms, from 2⁰ to 2¹⁰)

S₁₁ = 1(1 - 2¹¹)/(1 - 2) = (1 - 2048)/(-1) = 2047

Notice: this is 2¹¹ - 1. The sum of powers of 2 from 2⁰ to 2ⁿ always equals 2ⁿ⁺¹ - 1.

The Infinite Geometric Series

Here's where geometric series become magical.

If |r| < 1, then rⁿ → 0 as n → ∞.

The formula Sₙ = a₁(1 - rⁿ)/(1 - r) approaches:

S∞ = a₁/(1 - r), when |r| < 1

This is the sum of an infinite geometric series. It's finite. You add up infinitely many terms and get a definite number.

Example: 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + ...

a₁ = 1, r = 1/2

S∞ = 1/(1 - 1/2) = 1/(1/2) = 2

The infinite sum equals exactly 2.

Example: 0.333... = 3/10 + 3/100 + 3/1000 + ...

a₁ = 3/10, r = 1/10

S∞ = (3/10)/(1 - 1/10) = (3/10)/(9/10) = 3/9 = 1/3

This proves 0.333... = 1/3, using infinite series.

Why |r| < 1 Matters

When |r| < 1, each term is smaller than the last. The terms shrink fast enough that their infinite sum is bounded.

When |r| ≥ 1, the terms don't shrink (or grow). The sum diverges.

| r | Behavior |

|---|---|

| r | |

| r | |

| r = 1 | Diverges (sum = na₁ → ∞) |

| r = -1 | Oscillates (1 - 1 + 1 - 1 + ...) |

The boundary |r| = 1 is the threshold between finite and infinite sums.

Repeating Decimals as Geometric Series

Every repeating decimal is a geometric series in disguise.

0.777... = 7/10 + 7/100 + 7/1000 + ... = (7/10)/(1 - 1/10) = 7/9

0.454545... = 45/100 + 45/10000 + ... = (45/100)/(1 - 1/100) = 45/99 = 5/11

0.123123123... = 123/1000 + 123/1000000 + ... = (123/1000)/(1 - 1/1000) = 123/999 = 41/333

The geometric series formula proves that every repeating decimal is a rational number.

Present Value: Finance Uses This

If you'll receive $100 per year forever, starting next year, with 5% interest rate, what's that worth today?

Each payment must be discounted by the interest rate:

- Year 1: $100/(1.05)¹

- Year 2: $100/(1.05)²

- Year 3: $100/(1.05)³

- ...

Present value = 100/1.05 + 100/1.05² + 100/1.05³ + ...

a₁ = 100/1.05 ≈ 95.24, r = 1/1.05 ≈ 0.952

S∞ = (100/1.05)/(1 - 1/1.05) = (100/1.05)/(0.05/1.05) = 100/0.05 = $2,000

Infinite future payments have a finite present value. This is how annuities, bonds, and pensions are priced.

Compound Geometric Series

Sometimes you need to sum rᵏ where k ranges over specific values:

∑ₖ₌ₘⁿ rᵏ = rᵐ + rᵐ⁺¹ + ... + rⁿ

Factor out rᵐ: = rᵐ(1 + r + r² + ... + rⁿ⁻ᵐ) = rᵐ × (1 - rⁿ⁻ᵐ⁺¹)/(1 - r)

Starting at k = 0 isn't required. You can shift the starting point and adjust accordingly.

The Series 1 + r + r² + ... + rⁿ

This is the standard geometric series with a₁ = 1:

∑ₖ₌₀ⁿ rᵏ = (1 - rⁿ⁺¹)/(1 - r)

For |r| < 1 and n → ∞:

∑ₖ₌₀^∞ rᵏ = 1/(1 - r)

This formula is ubiquitous. It appears in:

- Power series expansions

- Probability (geometric distribution)

- Physics (summing reflections)

- Computer science (analyzing geometric algorithms)

When r Is Negative

Negative r means the terms alternate sign:

1 - 1/2 + 1/4 - 1/8 + ... (r = -1/2)

S∞ = 1/(1 - (-1/2)) = 1/(3/2) = 2/3

The partial sums oscillate but converge. Each positive term overshoots, each negative term corrects.

Alternating geometric series converge faster than same-sign series because the overshoots and undershoots partially cancel.

Why Geometric Series Matter

- They can converge. Unlike arithmetic series, geometric series can sum infinitely many terms to a finite result.

- The formula is simple. One expression handles all cases: Sₙ = a₁(1-rⁿ)/(1-r).

- They're everywhere. Compound interest, depreciation, probability, physics—anything with constant ratios generates geometric series.

- They connect to calculus. Taylor series generalize geometric series. The formula 1/(1-x) = 1 + x + x² + ... is the foundation of power series.

- They prove things. Repeating decimals are rational, Zeno's paradox is resolved, infinite sums make sense.

The geometric series formula is one of the most useful tools in mathematics. It transforms infinite addition into finite calculation.

Part 7 of the Sequences Series series.

Previous: Arithmetic Series: Summing Arithmetic Sequences Next: Infinite Series: When Sums Never Stop but Still Converge

Comments ()