Gibbs Free Energy: The Universe's Decision Function

In the 1870s, Josiah Willard Gibbs was a professor at Yale with no salary. He taught for free, published in obscure journals, and created the theoretical framework that would become the foundation of chemistry, materials science, and biochemistry.

His key insight: reactions don't just want to minimize energy. They don't just want to maximize entropy. They want to do both—and temperature decides the balance.

Gibbs combined these drives into one quantity. He called it the "available energy." We call it Gibbs free energy. It's the quantity the universe optimizes at constant temperature and pressure. It's the decision function that determines what happens next.

The Problem Gibbs Solved

Before Gibbs, chemists had two competing principles:

Berthelot's principle (1860s): Reactions proceed to minimize enthalpy. Exothermic reactions are favored.

The entropy principle: Reactions proceed to maximize entropy. Disorder is favored.

Both principles had counterexamples. Some endothermic reactions happen spontaneously (ice melting above 0°C absorbs heat). Some reactions decrease entropy yet proceed (crystallization).

Neither principle alone predicts reality. Gibbs realized: both matter, and temperature sets the weights.

The pebble: Reactions don't minimize energy or maximize entropy—they minimize free energy, which balances both.

The Definition

Gibbs free energy is defined as:

G = H - TS

Where: - G is Gibbs free energy - H is enthalpy (heat content at constant pressure) - T is absolute temperature (in Kelvin) - S is entropy

For a process at constant temperature and pressure, the change in Gibbs free energy is:

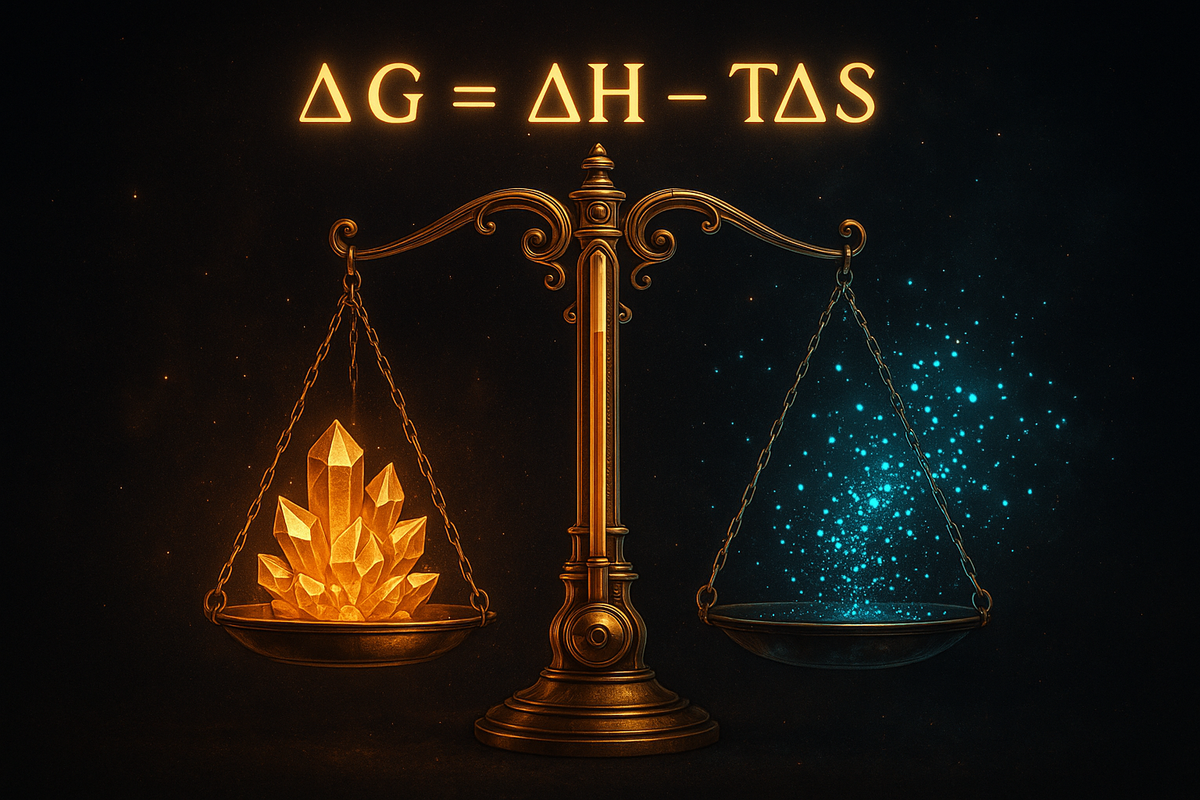

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

This equation is the universe's decision rule: - ΔG < 0: Process is spontaneous (thermodynamically favorable) - ΔG > 0: Process is non-spontaneous (requires energy input) - ΔG = 0: System is at equilibrium

Why "Free" Energy?

The word "free" means "available to do work."

Not all energy in a system is useful. Some is locked up, unavailable. The Gibbs free energy is the portion that can, in principle, be extracted as useful work at constant temperature and pressure.

When a reaction has ΔG < 0, it can drive other processes—like your muscles contracting or your neurons firing. That negative ΔG is the energy "freed up" by the reaction.

The pebble: Free energy is energy that's free to do something useful. The rest is thermodynamic overhead.

The Competition: Enthalpy vs Entropy

The equation ΔG = ΔH - TΔS sets up a competition:

Enthalpy (ΔH): Does the reaction release or absorb heat? - ΔH < 0 (exothermic): Favors reaction (makes ΔG more negative) - ΔH > 0 (endothermic): Opposes reaction (makes ΔG more positive)

Entropy (ΔS): Does the reaction increase or decrease disorder? - ΔS > 0 (entropy increase): Favors reaction (makes -TΔS negative) - ΔS < 0 (entropy decrease): Opposes reaction (makes -TΔS positive)

Temperature (T): How much does entropy matter? - High T: The -TΔS term dominates - Low T: The ΔH term dominates

This is why some reactions that don't happen at low temperature become spontaneous at high temperature—entropy becomes more important.

The Four Scenarios

| ΔH | ΔS | ΔG | Result | |----|----|----|--------| | − | + | Always − | Always spontaneous | | + | − | Always + | Never spontaneous | | − | − | − at low T, + at high T | Spontaneous when cold | | + | + | + at low T, − at high T | Spontaneous when hot |

The first two cases are simple: enthalpy and entropy agree or disagree completely. The last two are where temperature decides the winner.

Example of the third case: Freezing water. ΔH < 0 (releases heat), ΔS < 0 (ice is more ordered). At low temperature, enthalpy wins: water freezes. At high temperature, entropy wins: ice melts.

Example of the fourth case: Dissolving ammonium nitrate. ΔH > 0 (absorbs heat—the solution gets cold), ΔS > 0 (ions disperse). At high temperature, entropy wins: it dissolves. The cold pack in your first aid kit works this way.

Why Constant Temperature and Pressure?

Gibbs free energy applies at constant T and P. Why these conditions?

Because that's chemistry on Earth. Most reactions happen in open containers at atmospheric pressure. Temperature is controlled by surroundings. These are the conditions where G is the right thermodynamic potential.

At other conditions, different potentials apply: - Constant T and V: Use Helmholtz free energy (A = U - TS) - Constant S and P: Use enthalpy (H) - Constant S and V: Use internal energy (U)

But for most chemistry and biology, Gibbs is what you need.

The Second Law in Disguise

Gibbs free energy is the Second Law of Thermodynamics in practical form.

The Second Law says entropy of the universe increases. But tracking universal entropy is impractical. Gibbs free energy lets you focus on just your system, with the entropy cost automatically included.

When ΔG < 0 for your system, the universe's entropy increases (Second Law satisfied). The math guarantees this:

ΔS_universe = ΔS_system + ΔS_surroundings = ΔS_system - ΔH/T

If ΔG = ΔH - TΔS < 0, then ΔS_universe > 0.

The pebble: Gibbs free energy encodes the Second Law in a system-centered variable. You don't need to track the universe—just minimize G.

Standard Gibbs Free Energy

Chemists define standard conditions: 25°C (298 K), 1 atm pressure, 1 M concentration for solutions.

At standard conditions, the Gibbs free energy change for a reaction is written ΔG° (delta G naught). These values are tabulated for thousands of reactions.

To find ΔG° for a reaction, use standard free energies of formation:

ΔG°_rxn = Σ ΔG°_f(products) - Σ ΔG°_f(reactants)

This lets you predict spontaneity from tables, without doing calorimetry.

Gibbs Free Energy and Equilibrium

At equilibrium, ΔG = 0. The forward and reverse reactions are balanced. No net change occurs.

But ΔG° (standard) isn't usually zero. The relationship is:

ΔG = ΔG° + RT ln Q

Where Q is the reaction quotient (ratio of products to reactants). At equilibrium, Q = K (the equilibrium constant), and ΔG = 0:

ΔG° = -RT ln K

This equation connects thermodynamics (ΔG°) to the position of equilibrium (K). Large negative ΔG° means large K—reaction strongly favors products.

The Magnitude Matters

Not all spontaneous reactions are equal. The size of ΔG matters:

- ΔG = -1 kJ/mol: Weakly spontaneous, close to equilibrium - ΔG = -30 kJ/mol: Moderately spontaneous (like ATP hydrolysis) - ΔG = -200 kJ/mol: Strongly spontaneous, essentially irreversible

Large negative ΔG means the reaction drives hard toward products. The system has far to fall on the free energy landscape.

Coupled Reactions

Life exploits Gibbs free energy through coupled reactions.

A non-spontaneous reaction (ΔG > 0) can be driven by coupling it to a spontaneous one (ΔG < 0), as long as the total ΔG is negative.

ATP hydrolysis (ΔG ≈ -30.5 kJ/mol) is the cell's universal coupler. Reactions that would never happen alone become spontaneous when coupled to ATP breakdown. The favorable reaction drives the unfavorable one.

The pebble: Life runs on free energy coupling. Reactions that shouldn't happen do happen because they're yoked to reactions that must happen.

Why Gibbs Matters

Gibbs free energy is the master variable of chemistry and biochemistry:

- Predicts spontaneity: Will this reaction go? - Quantifies driving force: How hard does it push? - Determines equilibrium: Where does it settle? - Enables coupling: How can we make things happen?

Every drug binding to a receptor, every enzyme catalyzing a reaction, every protein folding into shape—all are navigating the Gibbs free energy landscape.

Gibbs the Person

Josiah Willard Gibbs (1839-1903) was a quiet revolutionary. He spent his entire career at Yale, publishing dense papers that most chemists couldn't understand. His "On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances" (1876-1878) contained the foundations of chemical thermodynamics, phase equilibria, and statistical mechanics—300 pages in the Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Sciences.

Maxwell recognized Gibbs' genius and built a plaster model of Gibbs' thermodynamic surface—the 3D representation of how entropy, energy, and volume relate. The model survives at Cambridge.

Gibbs received the Copley Medal, the Royal Society's highest honor, in 1901. He died two years later, having reshaped how we understand matter.

The pebble: Gibbs worked for free and published in obscurity. His equation now decides what happens in every chemical system on Earth.

Further Reading

- Atkins, P. & de Paula, J. (2014). Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. - Dill, K. & Bromberg, S. (2011). Molecular Driving Forces. Garland Science. - Gibbs, J. W. (1878). "On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances." Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences.

This is Part 1 of the Gibbs Free Energy series. Next: "The Formula: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS"

Comments ()