Green's Theorem: Relating Line and Double Integrals

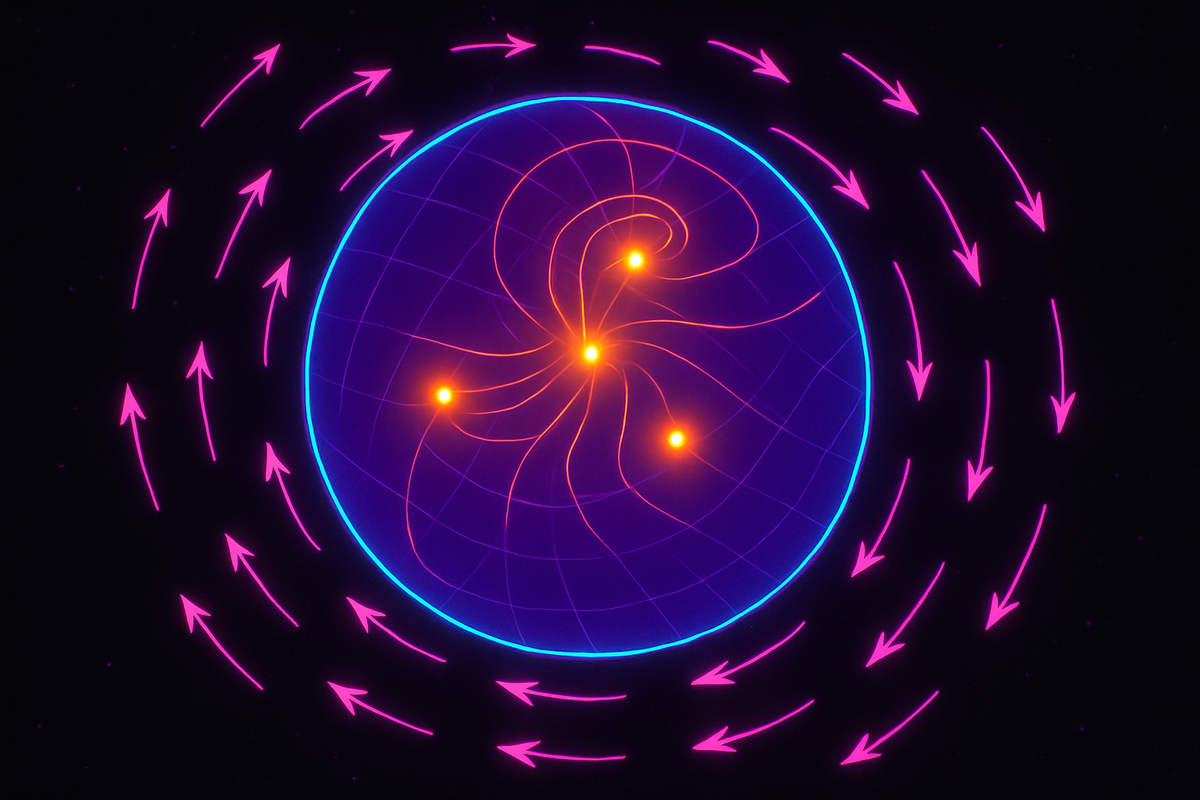

Green's Theorem connects a line integral around a closed curve to a double integral over the region it encloses. It says: the circulation around the boundary equals the total curl inside.

∫_C P dx + Q dy = ∬_R (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y) dA

where C is a simple closed curve (counterclockwise), R is the region it encloses, and F = (P, Q) is a vector field in 2D.

This is the fundamental theorem of calculus for 2D vector fields. Instead of ∫ f' = f(b) - f(a), you have ∫_boundary F = ∫∫_interior curl. Boundary behavior equals integrated interior structure.

The theorem transforms a hard integral (around a complicated curve) into an easier one (over a region), or vice versa. It also reveals that curl is the source of circulation—local rotation sums to global circulation around the boundary.

The Formula Unpacked

Left side: ∫_C P dx + Q dy

This is a line integral of the vector field F = (P, Q) around the closed curve C. It measures circulation—how much the field "goes around" the curve.

Right side: ∬_R (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y) dA

This is a double integral over the region R. The integrand is the 2D curl of F—a scalar in 2D, measuring rotation at each point. You're summing curl over the entire region.

The theorem: Circulation around the boundary = Total curl inside.

Why It's True: The Geometric Intuition

Imagine dividing the region R into tiny squares. For each square, the line integral around its boundary equals the curl inside (by a local version of the theorem).

Now add up all the squares. The interiors add up to ∬_R curl dA. The boundaries mostly cancel—each internal edge is traversed twice in opposite directions. Only the outer boundary C survives.

So ∑(line integrals around tiny squares) = ∫_C (outer boundary) = ∬_R curl dA.

This is the telescoping idea: interior contributions cancel, leaving only the boundary. It's the same principle as the fundamental theorem of calculus, but in 2D.

Example: Circular Region

Let F = (0, x), so P = 0 and Q = x.

Let C be the circle of radius a centered at the origin, traversed counterclockwise.

Left side (line integral): Parameterize: x = a cos t, y = a sin t, t ∈ [0, 2π] dx = -a sin t dt, dy = a cos t dt

∫_C P dx + Q dy = ∫_0^{2π} (0)(-a sin t) + (a cos t)(a cos t) dt = ∫_0^{2π} a² cos² t dt

Using cos² t = (1 + cos 2t)/2: ∫_0^{2π} a² cos² t dt = a² · π

Right side (double integral): ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y = ∂(x)/∂x - ∂(0)/∂y = 1 - 0 = 1

∬_R 1 dA = area of circle = πa²

Both sides equal πa². Green's Theorem checks out.

Applications: Calculating Area

If you set P = 0 and Q = x, Green's Theorem gives:

∫_C x dy = ∬_R 1 dA = area of R

The line integral of x dy around the boundary equals the area inside. This is a clever way to compute area: just integrate around the perimeter.

Alternatively, set P = -y and Q = 0:

-∫_C y dx = area of R

Or symmetrize: P = -y/2, Q = x/2:

∫_C (-y/2 dx + x/2 dy) = area of R

This is how planimeters work—mechanical devices that trace a curve and compute the enclosed area by measuring the line integral.

Curl in 2D

In 2D, curl is a scalar:

curl F = ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y

It measures rotation. Positive curl means counterclockwise rotation. Negative means clockwise. Zero means irrotational.

Green's Theorem says: ∫_C F · dr = ∬_R curl F dA

Circulation equals total curl. If the field rotates inside the region, there's circulation around the boundary. If curl is zero everywhere (irrotational field), circulation is zero.

Conservative Fields and Path Independence

If F is conservative (F = ∇φ for some potential φ), then ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y = 0. The curl is zero everywhere.

By Green's Theorem, ∫_C F · dr = 0 for any closed curve C.

This is path independence: the line integral from A to B doesn't depend on the path, because any two paths from A to B form a closed loop, and the integral around that loop is zero.

Green's Theorem explains why conservative fields have zero circulation: zero curl integrates to zero circulation.

Multiply Connected Regions

Green's Theorem extends to regions with holes. If R is a region with an outer boundary C and inner boundaries C₁, C₂, ..., Cₙ (all traversed so that R is on the left), then:

∫C F · dr - ∫{C₁} F · dr - ... - ∫_{Cₙ} F · dr = ∬_R curl F dA

The line integrals around the holes subtract because they're traversed in the opposite orientation.

Example: An annulus (ring-shaped region) has an outer circle and an inner circle. Green's Theorem relates the difference in circulation to the curl in the annulus.

Proof Sketch

For a rectangular region R = [a, b] × [c, d]:

Consider ∫_C P dx.

The horizontal edges contribute ∫_a^b P(x, c) dx - ∫_a^b P(x, d) dx.

By the fundamental theorem of calculus in the y-direction:

∫_a^b (P(x, c) - P(x, d)) dx = -∫_a^b ∫_c^d ∂P/∂y dy dx = -∬_R ∂P/∂y dA

Similarly, ∫_C Q dy = ∬_R ∂Q/∂x dA.

Adding: ∫_C P dx + Q dy = ∬_R (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y) dA.

For general regions, approximate with rectangles, take the limit, and the theorem follows.

This proof shows that Green's Theorem is essentially the fundamental theorem of calculus applied twice (once in each direction) and combined.

Flux Form of Green's Theorem

There's another version of Green's Theorem involving flux across the boundary:

∫_C F · n ds = ∬_R (∇ · F) dA

where n is the outward unit normal to C and ds is the arc length element.

This says: the flux out of the boundary equals the total divergence inside.

It's the 2D version of the Divergence Theorem. Instead of circulation and curl, it relates flux and divergence.

The two forms (circulation-curl and flux-divergence) are related by rotating the field 90 degrees. They're both instances of Green's Theorem.

Connection to Stokes' Theorem

Green's Theorem is a special case of Stokes' Theorem in 3D.

If you embed the 2D region R in the xy-plane of 3D space and extend the vector field F = (P, Q) to 3D as F = (P, Q, 0), then:

∇ × F = (0, 0, ∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y)

The curl is perpendicular to the plane, with magnitude equal to the 2D curl.

Stokes' Theorem says ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = ∫_C F · dr.

The surface S is the flat region R in the xy-plane, so (∇ × F) · dS = (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y) dA.

Thus Stokes' reduces to Green's in 2D. Green's Theorem is Stokes' Theorem for flat surfaces.

Applications in Physics

Green's Theorem appears in:

Fluid dynamics: Circulation of a velocity field equals the integrated vorticity in the region. Kelvin's circulation theorem uses this.

Electromagnetism: In magnetostatics, the line integral of B around a loop equals the current through the loop (Ampère's law). This is Green's Theorem for magnetic fields.

Complex analysis: For holomorphic functions f(z), Cauchy's theorem says ∫_C f(z) dz = 0. This follows from Green's Theorem, because the Cauchy-Riemann equations imply zero curl.

Work and energy: For a conservative force field, work around a closed path is zero. Green's Theorem explains this: conservative means zero curl, which integrates to zero circulation.

Computational Strategy

When should you use Green's Theorem?

Use it when the double integral is easier than the line integral. If C is a complicated curve but R is a simple region (rectangle, disk, etc.), convert to a double integral.

Use it when the line integral is easier than the double integral. If curl is complicated but the boundary is simple (circle, square), convert to a line integral.

Use it to check path independence. If curl is zero, all closed-loop integrals are zero, so the field is conservative.

Why Green's Theorem Matters

Green's Theorem is the first fundamental theorem of vector calculus. It connects:

- Line integrals (1D) to double integrals (2D)

- Boundary behavior to interior properties

- Circulation to curl

It's the prototype for Stokes' Theorem and the Divergence Theorem, which extend the same idea to 3D.

It reveals that curl is the source of circulation. Rotation in the interior causes the field to swirl around the boundary.

And it provides a practical tool for transforming integrals, often turning a hard calculation into an easy one.

Understanding Green's Theorem geometrically—why boundary circulation equals interior curl—is key to understanding the deeper structure of vector calculus. It's not just a computational trick. It's a statement about how local differential properties (curl at a point) integrate to global properties (circulation around a region).

Next, we'll generalize this to 3D with Stokes' Theorem, which relates surface integrals of curl to line integrals around the boundary. Green's is the flat case; Stokes' handles curved surfaces in 3D space.

Part 8 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: The Gradient Curl and Divergence: Del Operations Next: Stokes' Theorem: Generalizing Green's Theorem to Surfaces

Comments ()