The Nine Hallmarks of Aging: A Framework for Decline

Series: Longevity Science | Part: 1 of 7 Primary Tag: FRONTIER SCIENCE Keywords: hallmarks of aging, López-Otín, genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, longevity

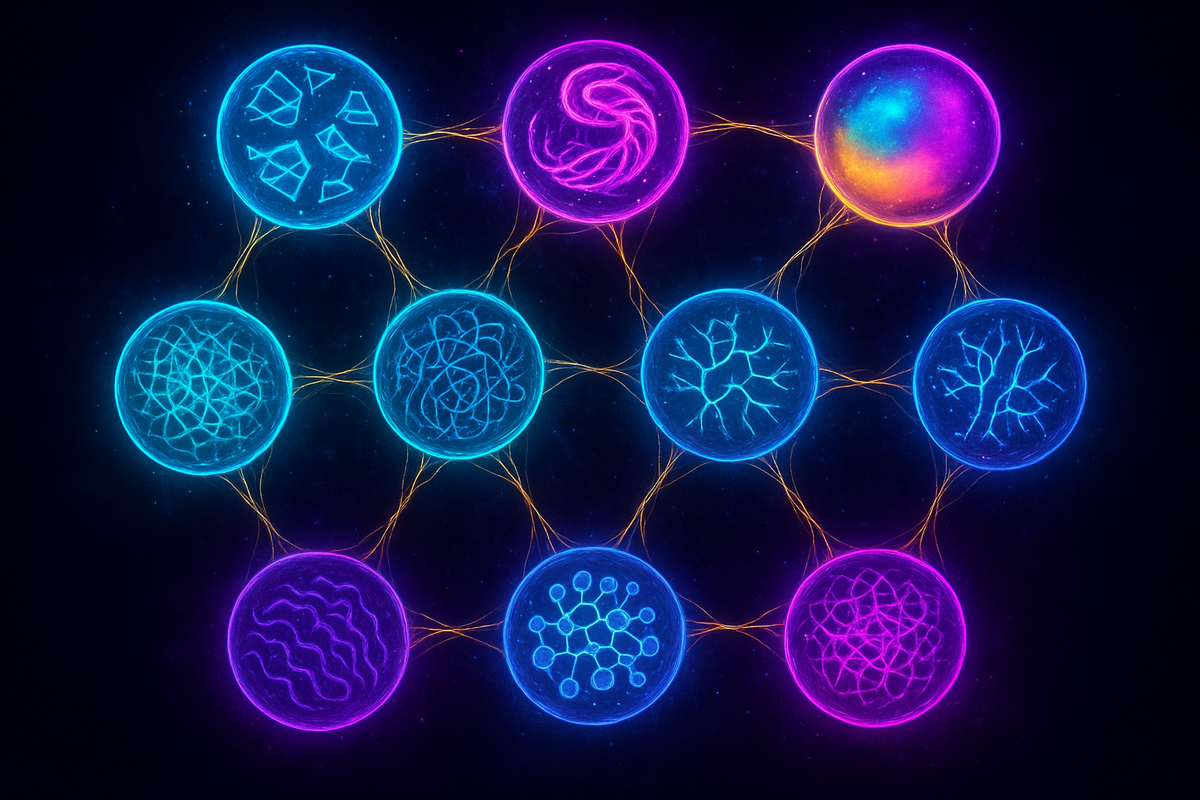

In 2013, a paper appeared in Cell that would reshape the entire field of aging research. Carlos López-Otín and colleagues proposed something audacious: a unified framework for understanding biological aging. Not a theory of why we age—there were plenty of those—but a systematic categorization of what happens as we age at the molecular and cellular level.

They called them the hallmarks of aging. Nine processes, interconnected and reinforcing, that together constitute biological decline. The framework was immediately influential because it did something rare in biology: it organized a chaotic field into something coherent.

Understanding these nine hallmarks is the starting point for understanding longevity science. Every intervention, every drug, every speculative therapy maps onto one or more of these processes. If you want to slow aging, you need to address the hallmarks. There's no other game in town.

The Framework

The hallmarks were organized into three tiers:

Primary hallmarks — The initial causes of cellular damage: 1. Genomic instability 2. Telomere attrition 3. Epigenetic alterations 4. Loss of proteostasis

Antagonistic hallmarks — Responses to damage that become harmful over time: 5. Deregulated nutrient sensing 6. Mitochondrial dysfunction 7. Cellular senescence

Integrative hallmarks — The downstream consequences affecting tissues: 8. Stem cell exhaustion 9. Altered intercellular communication

The beauty of this organization: the primary hallmarks cause damage, the antagonistic hallmarks are initially protective responses that become problematic, and the integrative hallmarks are the tissue-level manifestations of accumulated dysfunction. It's a cascade. Address the upstream causes, and you might prevent the downstream effects.

Let's walk through each one.

1. Genomic Instability

Your DNA is under constant assault. UV radiation, reactive oxygen species, replication errors, environmental mutagens—every day, each of your cells sustains thousands of DNA lesions. Most are repaired. Some aren't.

Over a lifetime, unrepaired damage accumulates. Point mutations. Chromosomal rearrangements. Copy number variations. The genome that emerged pristine from a fertilized egg gradually becomes corrupted.

This isn't just a cancer risk (though it is that). Genomic instability affects cellular function across the board. Genes get transcribed incorrectly. Proteins are made with wrong sequences. The information content of your cells degrades.

The evidence for genomic instability as an aging driver is extensive. Progerias—diseases of accelerated aging like Werner syndrome and Cockayne syndrome—are caused by mutations in DNA repair genes. Fix the repair machinery, and you fix the accelerated aging. Break the repair machinery, and you age faster.

Interventions targeting genomic instability would aim to enhance DNA repair, reduce mutagenic exposure, or perhaps eventually correct accumulated mutations through gene editing. We're not there yet, but the target is clear.

2. Telomere Attrition

Every time a cell divides, its telomeres—the repetitive DNA caps at chromosome ends—get a little shorter. This is a consequence of how DNA replication works: the replication machinery can't fully copy the very ends of linear chromosomes.

When telomeres get too short, cells stop dividing. This is the Hayflick limit, discovered in 1961: human cells can only divide about 40-60 times before they hit replicative senescence. It's a tumor suppression mechanism—uncontrolled division requires telomere maintenance—but it also limits tissue regeneration.

Telomere length correlates with age in most tissues. People with longer telomeres tend to live longer. Chronic stress, poor health behaviors, and disease all accelerate telomere shortening.

There's an enzyme, telomerase, that can rebuild telomeres. It's active in stem cells and germ cells, which is why those lineages can divide indefinitely. Most adult cells have telomerase silenced. Reactivating it could in principle extend replicative capacity—but might also enable cancer. This tension is one of the central challenges in telomere-based interventions.

3. Epigenetic Alterations

Here's something genuinely strange: your cells have essentially identical genomes but vastly different identities. A neuron and a liver cell contain the same DNA but express completely different gene sets. What makes them different isn't the genetic code—it's the epigenetic code. Chemical modifications to DNA (methylation) and the histone proteins that package DNA determine which genes are accessible and which are silenced.

This epigenetic landscape drifts with age. DNA methylation patterns change. Histone modifications shift. The careful programming that established cell identity during development gradually erodes.

The consequences are profound. Cells begin expressing genes they shouldn't and silencing genes they should express. The transcriptional program becomes noisy. Young cells have crisp identity; old cells have blurred identity.

What's remarkable is that this drift is so consistent that you can build an epigenetic clock—algorithms that predict biological age from DNA methylation patterns with startling accuracy. Steve Horvath and others have developed clocks that can tell your biological age within a few years, based purely on which genes are methylated.

This suggests epigenetic alterations aren't just random noise. They're patterned. And if they're patterned, they might be reversible. In fact, one of the most exciting areas in longevity research is epigenetic reprogramming—using factors that reset the epigenome to younger states. More on this later in the series.

4. Loss of Proteostasis

Proteins are the workhorses of the cell—enzymes, structural components, signaling molecules. They need to be properly folded to function. And they accumulate damage over time: oxidation, glycation, aggregation.

Cells have elaborate quality control systems—chaperones that help proteins fold correctly, and degradation systems (the proteasome and autophagy) that clear damaged or misfolded proteins. Young cells maintain proteostasis: protein homeostasis. Old cells don't.

The result: damaged proteins accumulate. Some aggregate into clumps—the plaques and tangles of Alzheimer's disease are the most famous example, but protein aggregation is a feature of aging across tissues. Even without forming visible aggregates, accumulated damaged proteins gum up cellular machinery.

Interventions targeting proteostasis aim to enhance autophagy (cellular self-cleaning) or support chaperone function. Rapamycin, one of the most studied longevity drugs, works partly through enhancing autophagy. Fasting and caloric restriction also activate autophagy—your cells, starved for resources, become more aggressive about recycling damaged components.

5. Deregulated Nutrient Sensing

Your cells are exquisitely sensitive to nutrient availability. When nutrients are abundant, cells grow and divide. When nutrients are scarce, cells hunker down, repair themselves, and wait. This makes evolutionary sense: grow when times are good, conserve when times are hard.

The signaling pathways that sense nutrients—insulin/IGF-1 signaling, mTOR, AMPK, and sirtuins—are among the most studied in longevity research. They're the pathways that mediate caloric restriction's effects.

Here's the puzzle: these pathways evolved for feast-and-famine cycles. You'd eat when food was available and fast when it wasn't. Modern humans eat constantly. Our nutrient-sensing pathways are permanently in "abundance" mode—promoting growth, suppressing repair.

This may be a mismatch disease. Chronically elevated insulin and mTOR signaling promote aging-related diseases: diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease. Interventions that dial down these pathways—caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, drugs like rapamycin and metformin—extend lifespan in nearly every organism tested.

The antagonistic hallmark logic applies here: nutrient sensing is necessary and beneficial, but chronic activation in modern environments becomes harmful.

6. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

We covered mitochondria extensively in an earlier series, but they deserve mention here. Mitochondria are the power plants of cells, generating ATP through oxidative phosphorylation. They also produce reactive oxygen species as a byproduct—free radicals that can damage cellular components.

With age, mitochondria become dysfunctional. Their DNA accumulates mutations (mitochondria have their own genome, with less robust repair than nuclear DNA). Their electron transport chains become leaky, producing more reactive oxygen species. Their dynamics—the constant fusion and fission that maintains mitochondrial health—become deranged.

The result: cells become energy-deficient and oxidatively stressed. Tissues with high energy demands—brain, heart, muscle—are particularly vulnerable.

Interventions targeting mitochondrial dysfunction include NAD+ precursors (NAD+ is essential for mitochondrial function and declines with age), compounds that enhance mitophagy (clearance of damaged mitochondria), and potentially mitochondrial transplant or gene therapy.

7. Cellular Senescence

When cells experience severe stress or damage—unrepairable DNA breaks, telomere crisis, oncogene activation—they have a choice: die (apoptosis) or stop dividing permanently (senescence). Senescence is a tumor suppression mechanism: better to stop a damaged cell from dividing than to risk it becoming cancerous.

But senescent cells don't just sit quietly. They secrete a cocktail of inflammatory molecules, proteases, and growth factors called the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). This SASP poisons the cellular neighborhood, promoting inflammation, disrupting tissue structure, and—ironically—potentially promoting cancer in surrounding cells.

Young bodies clear senescent cells efficiently. Old bodies don't. Senescent cells accumulate with age, their SASP creating chronic inflammation (sometimes called "inflammaging") that contributes to virtually every age-related disease.

Senolytics—drugs that selectively kill senescent cells—are among the most promising near-term longevity interventions. In mouse studies, clearing senescent cells extends healthspan, reverses age-related pathology, and increases lifespan. Human trials are underway. We'll cover this in detail in a later article.

8. Stem Cell Exhaustion

Tissues maintain themselves through stem cells—reserve populations that can divide and differentiate to replace lost or damaged cells. Your blood, skin, gut, and other tissues are continuously regenerated from stem cells.

With age, stem cell function declines. Stem cell pools shrink. The cells that remain become less capable of self-renewal and differentiation. They accumulate the same damage—genomic, epigenetic, proteostatic—that affects all cells.

The consequence: tissues lose regenerative capacity. Wounds heal slower. Blood cell production falters. Muscles don't recover from injury. The reserve army that kept tissues young runs out of soldiers.

Stem cell exhaustion is partly downstream of the other hallmarks—stem cells age because of genomic instability, epigenetic drift, and senescent cell SASP. But it's also a master integrator: whatever damages stem cells echoes through the tissues they support.

Interventions might include rejuvenating endogenous stem cells (through epigenetic reprogramming or removing senescent cells from stem cell niches) or supplementing with exogenous stem cells. The latter is scientifically fraught—most "stem cell clinics" are selling snake oil—but the legitimate research is ongoing.

9. Altered Intercellular Communication

Cells don't exist in isolation. They're embedded in tissues, communicating constantly through signaling molecules, direct contact, and extracellular matrix. Aging alters this communication.

Chronic low-grade inflammation is the most studied example. With age, inflammatory signaling increases systemically—even without infection or injury. This "inflammaging" is driven partly by senescent cells' SASP, partly by gut barrier breakdown (allowing bacterial products into circulation), and partly by deranged immune function.

But it's not just inflammation. Hormone signaling changes. Growth factor gradients shift. The extracellular matrix stiffens and accumulates cross-links. The signals that young tissues use to coordinate function become corrupted.

This hallmark is integrative because it's about system-level dysfunction. Individual cells might be relatively healthy, but if their communication is deranged, tissue function suffers. It's another example of coherence loss: the coupling between components breaks down.

Interventions targeting intercellular communication include anti-inflammatory approaches, interventions that restore gut barrier function (there's the microbiome connection), and potentially systemic factors from young blood that might restore youthful signaling environments.

The Interconnections

What makes the hallmarks framework powerful isn't just the list—it's the connections. The hallmarks feed each other in reinforcing loops:

- Genomic instability causes epigenetic alterations (DNA damage triggers epigenetic changes) - Epigenetic alterations cause genomic instability (epigenetic dysregulation leads to replication errors) - Mitochondrial dysfunction increases reactive oxygen species, causing genomic instability - Cellular senescence is triggered by multiple primary hallmarks and amplifies others through SASP - Stem cell exhaustion results from accumulated damage and limits tissue repair capacity - Altered intercellular communication both results from and causes dysfunction in individual cells

Aging isn't nine separate problems. It's one interconnected system in which dysfunction propagates across levels. This is why single-target interventions often disappoint: fix one hallmark, and the others are still driving decline.

The most promising approaches address multiple hallmarks simultaneously. Caloric restriction affects nutrient sensing, mitochondrial function, proteostasis, and senescence. Rapamycin hits mTOR (nutrient sensing) but also enhances autophagy (proteostasis) and reduces senescence. Epigenetic reprogramming might reset multiple hallmarks at once.

Updates to the Framework

The original 2013 paper proposed nine hallmarks. In 2023, López-Otín and colleagues published an update, adding three more:

- Disabled macroautophagy (elevated from part of proteostasis to its own hallmark) - Chronic inflammation (elevated from part of intercellular communication) - Dysbiosis (the microbiome connection—finally recognized as a hallmark)

The field is still debating whether these additions improve or dilute the framework. But the core insight remains: aging is multi-causal, interconnected, and potentially addressable at multiple points.

The Practical Implication

Here's what the hallmarks framework tells us: there's no magic bullet for aging. Anyone selling you one intervention to stop aging is overselling. The process involves nine (or twelve) interconnected mechanisms across multiple biological scales.

But it also tells us: the mechanisms are knowable. They're being studied. And interventions that target multiple hallmarks—caloric restriction, fasting, exercise, certain drugs—do extend healthspan in animal models and show promise in humans.

The hallmarks are the map. The interventions we'll discuss in the coming articles are attempts to navigate that map toward longer, healthier lives.

Further Reading

- López-Otín, C. et al. (2013). "The Hallmarks of Aging." Cell. - López-Otín, C. et al. (2023). "Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe." Cell. - Kennedy, B.K. et al. (2014). "Geroscience: Linking Aging to Chronic Disease." Cell. - Campisi, J. et al. (2019). "From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing." Nature.

This is Part 1 of the Longevity Science series, exploring the biology of aging and interventions to extend healthspan. Next: "Is Aging a Disease? The Case for Programming."

Comments ()