Holes, Loops, and Voids: The Topology of Getting Stuck

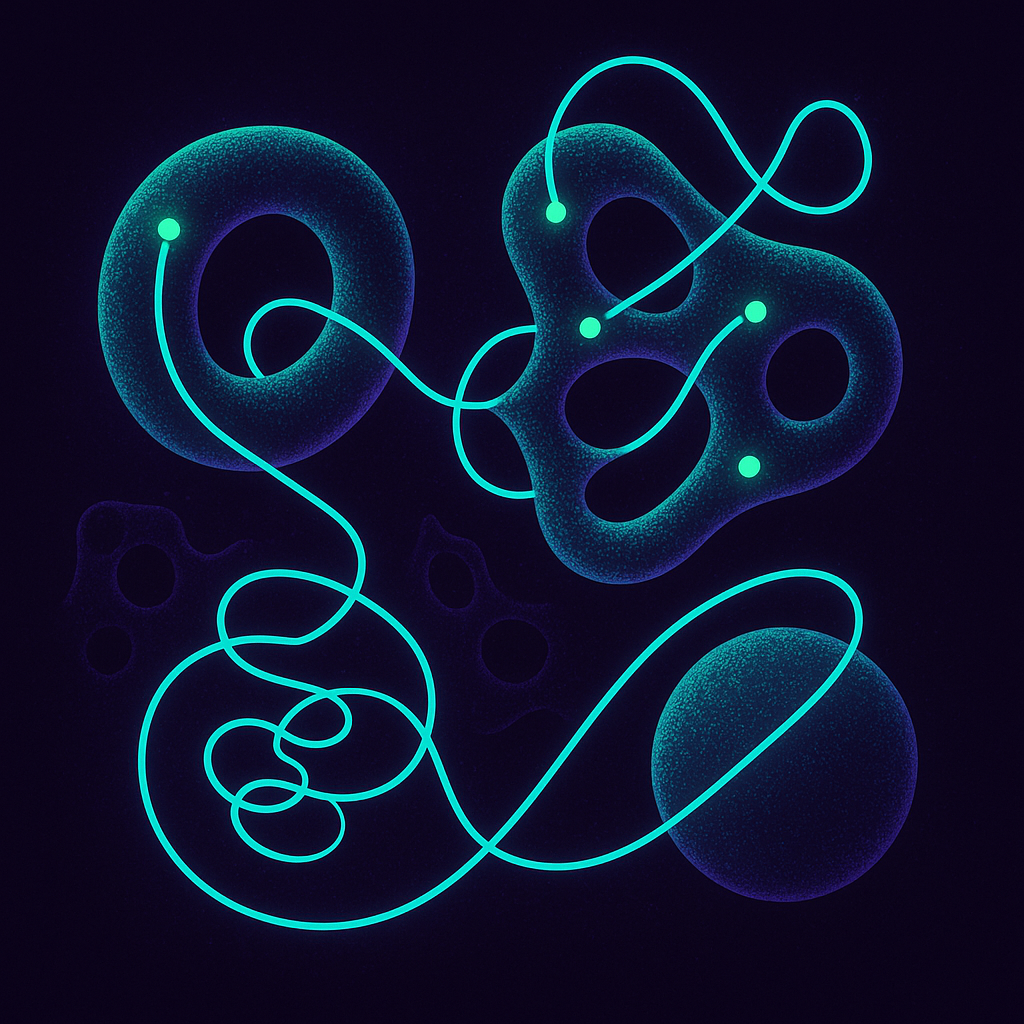

Betti numbers expose the structural shape of belief systems and relationships. Topological features—disconnection, recurring loops, sealed voids—resist change more than any geometry.

Holes, Loops, and Voids: The Topology of Getting Stuck

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

You've been here before.

Not this exact moment, but this pattern. This argument with the same shape as a hundred previous arguments. This relationship dynamic that keeps recurring no matter who you're with. This organizational dysfunction that persists through leadership changes, restructures, and strategic pivots. This cultural conflict that echoes across decades.

You're not imagining the repetition. The pattern is real. But the pattern isn't about content—what you're arguing about, who you're arguing with. It's about structure. Something in the shape of the space you're navigating keeps routing you back to the same place.

This is topology. Not the local geometry of curvature and distance, but the global structure of what's connected to what, what's missing, and what persists across all possible deformations.

Topology explains why some patterns are so hard to escape—not because you lack willpower or insight, but because the space itself has features that trap trajectories. Holes you can't cross. Loops you can't exit. Voids you can't fill.

What Topology Sees

Geometry asks: how far apart are two points? How curved is the surface here?

Topology asks different questions: Is this space connected? Are there holes in it? Can you get from here to there at all?

Topology is geometry's more abstract cousin. It doesn't care about exact distances or precise curvatures. It cares about properties that survive continuous deformation—stretching, bending, morphing—without tearing or gluing.

A coffee cup and a donut are topologically the same. Both have one hole. You can continuously deform one into the other without cutting or pasting. A sphere and a cube are topologically the same—no holes, and you can morph between them smoothly. But a sphere and a donut are topologically different. No amount of smooth deformation turns one into the other. The hole is the difference.

This might seem like mathematical abstraction with no bearing on minds or meaning. It's not. The topology of a space determines what paths are possible—what you can reach from where you are, what loops you might get caught in, what regions are inaccessible no matter how hard you try.

Belief manifolds have topology. And that topology shapes everything.

Persistent Homology

The mathematical tool for analyzing topology is called persistent homology. The name is intimidating; the idea is intuitive.

Persistent homology asks: what features of a space persist across different scales of observation?

Imagine looking at a landscape through increasingly blurry lenses. At high resolution, you see every detail—tiny bumps, small crevices, minor variations. As you blur, small features disappear. Only the large-scale structure remains. The features that persist across many levels of blur are the real structure. The features that vanish quickly were just noise.

Persistent homology does this mathematically. It identifies features of different types—connected components, loops, voids—and tracks which ones persist across scales. Long-persisting features are topologically significant. They're the real structure of the space, not artifacts of how you're looking at it.

The outputs are Betti numbers, named after the mathematician Enrico Betti. They count topological features:

β₀ (Betti zero) counts connected components. How many separate pieces is the space broken into? A space with β₀ = 1 is all one piece. A space with β₀ = 3 has three disconnected regions.

β₁ (Betti one) counts loops—one-dimensional holes that you can walk around but not through. A donut has β₁ = 1. A figure-eight has β₁ = 2. A sphere has β₁ = 0.

β₂ (Betti two) counts voids—two-dimensional holes, enclosed cavities. A hollow sphere has β₂ = 1 (the interior is a void). A solid ball has β₂ = 0.

These numbers characterize the global structure of a space in ways that local geometry misses. And they appear in minds, relationships, and cultures in ways that explain why certain patterns are so persistent.

Fragmentation: When β₀ > 1

A healthy belief manifold is connected. You can get from any belief to any other belief through some path—maybe a long path, maybe a difficult path, but a path. The space is one piece.

Trauma can fragment the manifold. The space breaks into disconnected regions. β₀ increases from 1 to 2 or more. Now there are beliefs that cannot reach each other—not because the path is hard, but because no path exists.

This is dissociation, topologically understood.

In dissociative states, aspects of experience that should connect don't. Memory in one region, emotion in another, body sensation in a third—and no path linking them. You can know something happened without feeling that it happened to you. You can feel terror without knowing why. The experiences exist, but in topologically separate regions.

The therapeutic task, in this frame, is topological repair. Not just processing content but rebuilding connections—creating paths between regions that have become disconnected. This is slow work because you're not just traversing difficult terrain; you're building bridges where no terrain exists.

Some therapeutic approaches do this explicitly. Parts work in Internal Family Systems maps the fragmented regions and works to establish communication between them. EMDR's bilateral stimulation may create cross-hemispheric bridges that reconnect partitioned processing. Somatic therapies work to reconnect body and narrative, building paths through experiential space.

The topology has to change. Understanding alone doesn't do it. You can understand perfectly well that these regions should connect and still not have any path between them.

Loops: When β₁ > 0

A loop is a path that returns to its starting point without crossing itself. On a flat plane, you can always shrink a loop to a point—pull it tight until it disappears. On a donut, some loops can't be shrunk. They go around the hole. No amount of continuous deformation eliminates them.

Belief manifolds can have loops too. Persistent loops that trajectories get caught in. You travel through a sequence of states and end up back where you started, unable to exit.

This is rumination.

The ruminative mind isn't stuck at a point. It's stuck on a loop. It moves—from worry to catastrophizing to self-criticism to attempted solution to failure back to worry. There's motion. It's just motion that goes nowhere.

The loop persists because of the topology. It wraps around a hole—something missing from the manifold, something that should be there but isn't. The absence creates the trap. You can't exit the loop because exiting would require crossing the hole, and you can't cross what doesn't exist.

What's the hole? Often, it's an unprocessed experience. An event that couldn't be integrated. A reality that couldn't be modeled. The manifold formed around it, and now all paths in that region wrap around the absence.

Addiction has loop structure. The cycle of craving, using, relief, crash, withdrawal, craving—it's topological. The loop persists because something is missing at the center. Connection, meaning, regulation—whatever the substance was trying to provide. The loop wraps around the void where that thing should be.

Breaking addiction isn't just about interrupting the behavior. It's about filling the hole. Providing what's missing so that the loop can finally collapse. As long as the void remains, the topology remains, and the loop persists.

Organizations have loops too. Dysfunctional processes that keep cycling—the same problems addressed at the same meetings with the same non-solutions, year after year. The loop persists because something is missing from the organizational manifold. The thing that would allow actual change is absent, so all motion wraps around the absence.

Voids: When β₂ > 0

Voids are harder to visualize. A void is an enclosed empty region—a cavity in the space that nothing can access.

In a belief manifold, a void might be a region of experience that's been completely sealed off. Not just disconnected (fragmentation) or circled around (loops), but enclosed. Walled off. The manifold curves around it in every direction, making it inaccessible from anywhere.

This is more severe than dissociation. It's erasure. Experience that has been so thoroughly excluded that the manifold has no representation of it at all.

Sometimes this is protective. The void contains something so destabilizing that the system couldn't survive exposure to it. Better to seal it away entirely than risk contact.

But voids create problems. The manifold distorts around them. Every path near the void bends away from it. The system develops systematic blindnesses—things it cannot see, cannot think, cannot approach—because the topology makes approach impossible.

Some therapeutic breakthroughs involve the sudden discovery of a void—something that was always there but that the manifold was shaped to exclude. The breakthrough is the void becoming visible. Now it's no longer topologically sealed. Paths can start to form. Integration becomes possible.

This is often what's happening when someone says "I had no idea that was there" about some aspect of their own experience. They literally didn't. The topology made it inaccessible. The void has been part of the structure all along, shaping everything without being seen.

Topological Persistence in Relationships

Relational patterns persist topologically.

You leave a dysfunctional relationship and enter a new one. Different person, different context, same pattern. Why?

One answer: you brought the topology with you.

Your relational manifold has a certain shape—loops, maybe voids, certain regions inaccessible. When you enter a new relationship, you navigate with the manifold you have. If that manifold has a loop in it, you'll find the loop again. Not because you're choosing it consciously, but because it's built into the structure of how you move through relational space.

This is the geometric basis of repetition compulsion. The system keeps finding the same patterns because the topology keeps routing it there. The content changes—new partner, new job, new city—but the structure persists.

Changing this requires changing the topology, not just the content. Which means therapeutic work isn't primarily about understanding the pattern (though understanding helps). It's about restructuring the manifold itself—filling holes, opening new paths, collapsing loops that no longer need to persist.

This is slow work. Topology is more resistant to change than geometry. You can smooth curvature through repeated experience. You can reduce divergence through model updating. But changing topology requires something more dramatic—building what doesn't exist, bridging what's disconnected, finding what's been sealed away.

Organizations as Topological Systems

Organizations have topology too.

A healthy organization is connected. Information can flow from any part to any other. Decisions made in one region affect and are informed by other regions. The manifold is one piece.

Silos are topological fragmentation. When β₀ > 1, you have multiple disconnected organizational regions. Information doesn't flow because paths don't exist. It's not that people refuse to communicate—there are no channels for communication, no shared context, no connection.

Organizational loops show up as process dysfunctions that persist despite everyone knowing they're dysfunctional. The quarterly review that never changes anything. The initiative cycle that always ends the same way. Everyone can see the loop. No one can exit it. Because the loop exists in the topology, in the structure of how organizational states connect, not just in the decisions of individuals.

Organizational voids show up as systematic blind spots. Things the organization cannot perceive, cannot discuss, cannot address—not because of individual cowardice or politics (though those exist) but because the topology has sealed them away. The founder's original sin that cannot be named. The market reality that contradicts the business model. The cultural problem that would require admitting the culture is broken.

Organizational change often fails because it addresses content without addressing topology. You can replace every person, change every process, rewrite every strategy document—but if the topology persists, the patterns will reassert themselves. The new people will route around the same holes, get caught in the same loops, fail to see the same voids.

Real organizational transformation requires topological change. Building bridges where silos exist. Collapsing loops by filling what's missing. Opening voids by making the undiscussable discussable. This is why transformation is so hard and so rare. It's not just changing what people do—it's changing the shape of the space they're operating in.

Cultural Topology

Scale up again. Cultures have topology.

A coherent culture is connected across its diversity. Different groups, different regions, different beliefs—but paths connect them. You can get from one cultural position to another through conversation, through shared institutions, through common reference points. The space is one piece.

Polarization is cultural fragmentation. When political or social groups occupy disconnected regions of the cultural manifold, β₀ > 1. It's not that they disagree—disagreement happens within a connected space. It's that there's no path from one worldview to another. The space has broken.

Cultural loops show up as historical patterns that repeat. The same conflicts, the same dynamics, the same mistakes—generation after generation. The loop wraps around something unprocessed in the collective history. An original wound, an unintegrated trauma, a void at the center of the culture that all patterns circle around.

Cultural voids are the things a culture cannot think. Not taboos exactly—taboos are visible, even if forbidden. Voids are invisible. They're the questions that can't be asked because the cultural manifold has no representation for them. They're the options that can't be considered because the topology has sealed them away.

Cultural change, like individual and organizational change, requires topological transformation. Bridging fragmentation. Collapsing destructive loops. Opening voids to inspection. This is the work of reconciliation, of cultural healing, of genuine progress. It's why such work is so difficult and so rare.

The Persistence of Topology

Topology is sticky.

Geometric properties—curvature, distance—can change gradually through repeated experience. You can smooth a sharp curve by traversing it many times safely. You can close a KL divergence gap through model updating.

Topological properties resist this kind of gradual change. A hole doesn't get smaller through repeated circulation around it. A fragmentation doesn't heal just because you keep bumping into the boundary. A void doesn't open just because you keep approaching where it should be.

Changing topology requires discontinuous events. Something has to bridge, to connect, to open. A fragmented manifold becomes connected when a path is built that didn't exist before—not when existing paths are improved. A loop collapses when the hole it surrounds is filled—not when the loop is traversed more smoothly.

This is why patterns persist despite insight, despite motivation, despite apparently successful intervention. Understanding a pattern, even understanding it perfectly, doesn't change the topology. You can know exactly why you keep ending up in the same place and keep ending up there anyway. The knowing happens in one region of the manifold. The pattern lives in the topology. They don't automatically affect each other.

What changes topology? Often, relationships. A new connection that bridges what was disconnected. An experience with someone whose manifold has paths yours lacks—and through coupling, some of those paths transfer. Therapy works partly through this mechanism: the therapist's manifold, in coupling with the client's, provides topological scaffolding that the client's manifold alone doesn't have.

Sometimes crisis changes topology. An event so significant that the manifold restructures around it. Not always for the better—trauma can create new fragmentation, new loops, new voids. But sometimes crisis opens what was closed, connects what was fragmented, collapses what was trapped.

And sometimes slow accumulation changes topology. Not single experiences but many experiences, each one depositing a little material into the hole until eventually the hole is filled. This is the work of years. It's why genuine transformation is rarely quick.

Finding the Holes

You can't change topology you can't see. The first step is identification: where are the holes, loops, and voids in your manifold?

Loops announce themselves through repetition. The pattern you keep finding. The place you keep returning to despite intending to go elsewhere. Where do your trajectories circle? What's at the center?

Fragmentation announces itself through disconnection. The aspects of experience that don't talk to each other. The parts of yourself that feel like different people. The regions of your life that exist in separate worlds. Where are the gaps? What can't you get to from here?

Voids are harder because they're invisible by definition. They announce themselves through distortion—through the way everything near them bends away. What topics make you inexplicably uncomfortable in ways you can't explain? What questions feel somehow impossible to even formulate? Where does your mind slide away without choosing to?

These are diagnostic questions, not solutions. Knowing where the topology is broken doesn't fix it. But it tells you what kind of work is needed. Smoothing curvature won't help a fragmentation. Reducing divergence won't collapse a loop. The intervention has to match the problem.

Topology is the architecture of stuckness. Understanding it doesn't set you free. But it shows you what the prison is made of. And that's the first step toward finding the door.

Comments ()