Hypothesis Testing: Is the Effect Real?

You give 100 people a new drug. Their symptoms improve. Success?

Not so fast. Maybe they got better on their own. Maybe it's placebo effect. Maybe you just got lucky with this sample.

How do you know if the drug actually works—or if you're just seeing noise?

That's what hypothesis testing answers. It's the machinery for deciding: "Is this pattern real, or just random chance?"

And the answer is not yes or no. It's probabilistic. Hypothesis testing tells you: "If the drug did nothing, how surprised should I be by this result?"

Very surprised? Probably the drug works.

Not surprised? You can't rule out random chance.

But here's the problem: most people—including most scientists—don't understand what hypothesis testing actually measures. They think "statistically significant" means "probably true." It doesn't.

And that confusion is why the replication crisis happened.

This article explains the logic of hypothesis testing, what p-values actually mean, and why "statistically significant" is one of the most misunderstood phrases in science.

The Core Logic: Proof by Contradiction

Hypothesis testing works like a mathematical proof by contradiction. You can't prove your hypothesis is true. But you can show that the opposite is implausible.

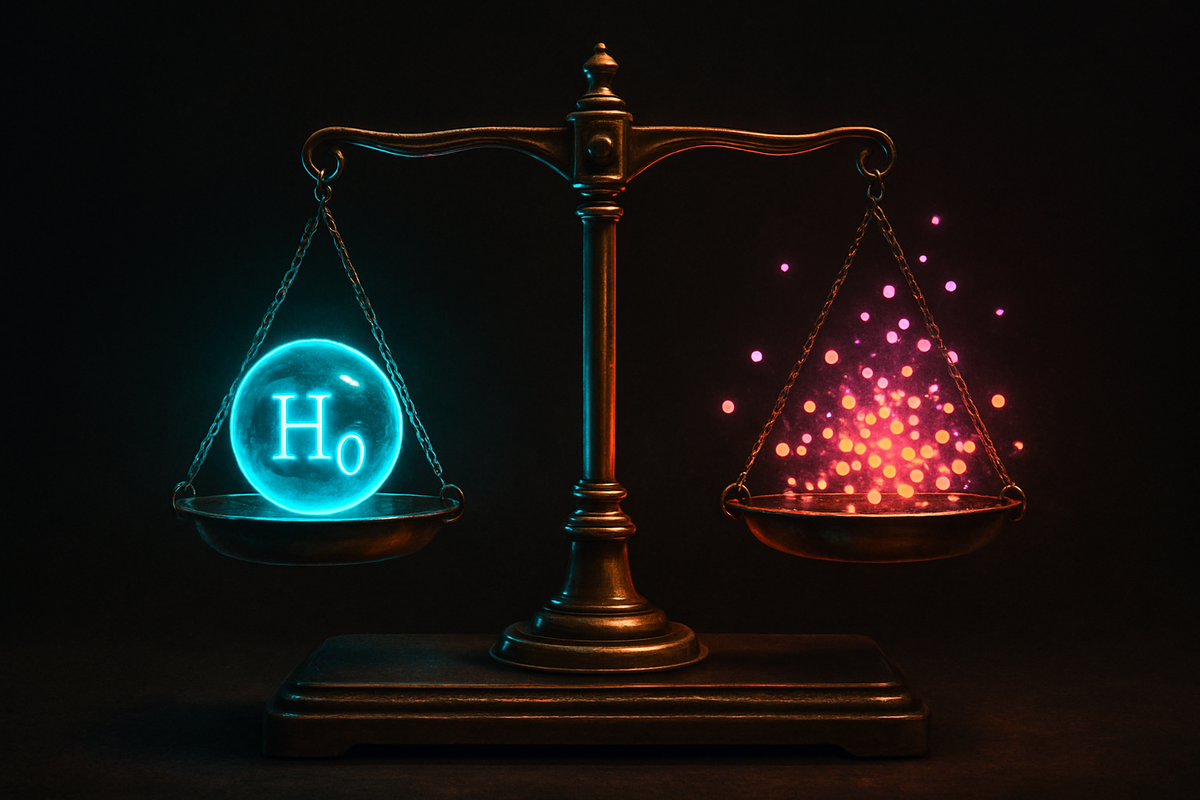

The Null Hypothesis ($H_0$)

The null hypothesis is the boring, skeptical claim: "Nothing is happening. The drug doesn't work. The groups are the same. The effect is zero."

You start by assuming the null is true. Then you calculate: "How likely is my data, if the null were true?"

If the data would be very unlikely under the null, you reject the null. You conclude: "Probably something is happening."

If the data is reasonably likely under the null, you fail to reject the null. You conclude: "I can't rule out random chance."

Notice: you never "accept" the null. You just say "I don't have enough evidence to reject it."

And you never "prove" the alternative. You just say "the null seems implausible."

The Alternative Hypothesis ($H_1$ or $H_a$)

This is what you're actually interested in: "The drug works. The groups differ. The effect is non-zero."

But hypothesis testing doesn't work by proving the alternative. It works by showing the null is inconsistent with the data.

Why this roundabout logic?

Because you can calculate probabilities under the null. The null is simple—it specifies an exact parameter value (e.g., "effect size = 0"). You can model what data should look like if the null is true.

The alternative is vague—"effect size ≠ 0" doesn't tell you how large the effect is. You can't calculate exact probabilities under it.

So you test the null, not the alternative. That's why it's called "null hypothesis significance testing" (NHST).

The Procedure: How Hypothesis Testing Works

Here's the step-by-step:

1. State Your Hypotheses

Null hypothesis ($H_0$): "The drug has no effect."

Alternative hypothesis ($H_1$): "The drug has an effect."

Be specific. Are you testing "effect = 0" vs. "effect ≠ 0"? (Two-tailed test.)

Or "effect = 0" vs. "effect > 0"? (One-tailed test.)

2. Choose a Significance Level ($\alpha$)

This is your error tolerance. How much false-positive risk are you willing to accept?

Conventionally, $\alpha = 0.05$. That means: "If I reject the null, there's a 5% chance I'm wrong (the null was actually true, and I just got unlucky data)."

You choose $\alpha$ before collecting data. It's a threshold, not a result.

3. Collect Data

Run your experiment. Measure outcomes. Calculate your test statistic (more on this below).

4. Calculate the p-Value

The p-value is the probability of observing data at least as extreme as what you saw, if the null hypothesis were true.

Low p-value = "This data would be very surprising if the null were true."

High p-value = "This data is consistent with the null."

5. Compare p-Value to $\alpha$

- If $p < \alpha$: Reject the null. The effect is "statistically significant."

- If $p \geq \alpha$: Fail to reject the null. The result is "not significant."

6. Interpret the Result

If you reject the null: "There's evidence of an effect. But we don't know how large it is, and we might be wrong (5% false-positive rate)."

If you fail to reject: "We don't have enough evidence to conclude there's an effect. Maybe there is one, but it's too small to detect with this sample size. Or maybe there isn't."

Notice: you never say "the null is true" or "the alternative is proven." You only quantify evidence against the null.

Test Statistics: Converting Data to a Number

Different tests use different test statistics—a single number that summarizes how extreme your data is.

t-Test: Comparing Means

You're comparing two groups (drug vs. placebo). You calculate the difference in means, scaled by the variability:

$$t = \frac{\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}2}{\text{SE}{\text{diff}}}$$

Where $\text{SE}_{\text{diff}}$ is the standard error of the difference.

Intuition: If the groups are very different relative to the noise, $t$ is large. If they're barely different, $t$ is small.

You then calculate: "How likely is a $t$ this large (or larger) if the null is true?"

That's the p-value. You look it up in a t-distribution table (or let software calculate it).

Z-Test: Proportions or Large Samples

If you're testing proportions (e.g., "Do 50% of voters support this policy?") or have a large sample with known variance, you use the Z-test.

$$Z = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu_0}{\text{SE}}$$

Where $\mu_0$ is the hypothesized mean under the null.

The p-value comes from the standard normal distribution.

Chi-Square Test: Categorical Data

Testing independence between two categorical variables? Use $\chi^2$ (chi-square).

It measures how much the observed frequencies deviate from what you'd expect if the variables were independent.

$$\chi^2 = \sum \frac{(O - E)^2}{E}$$

Where $O$ = observed, $E$ = expected.

Large $\chi^2$ = big deviation = reject independence.

F-Test: Variance Ratios (ANOVA)

Comparing more than two groups? Use ANOVA, which relies on the F-statistic.

$$F = \frac{\text{Variance between groups}}{\text{Variance within groups}}$$

If $F$ is large, the groups differ more than you'd expect by chance.

One-Tailed vs. Two-Tailed Tests

This distinction trips people up.

Two-Tailed Test

Null: "The effect is zero."

Alternative: "The effect is non-zero—could be positive or negative."

You're testing for any difference, regardless of direction.

p-value: You calculate the probability of an effect at least as extreme in either direction.

Use this when you don't have a directional prediction.

One-Tailed Test

Null: "The effect is zero (or negative)."

Alternative: "The effect is positive."

You're only testing for a difference in one direction.

p-value: You only consider extremes in the predicted direction.

This makes it easier to reject the null. For the same data, a one-tailed test gives you half the p-value of a two-tailed test.

The temptation: Use a one-tailed test to get "significance" more easily.

The problem: You're ignoring the other direction. If the effect goes the opposite way (e.g., the drug makes things worse), a one-tailed test won't detect it.

The rule: Only use one-tailed tests if you have a strong a priori reason to predict a direction. And specify this before seeing the data. Otherwise, use two-tailed.

Statistical Significance: What It Does and Doesn't Mean

You run your test. You get $p = 0.03$. That's less than $\alpha = 0.05$. You declare: "The result is statistically significant."

What does that mean?

What It Means

"If the null hypothesis were true, this data (or more extreme) would occur less than 5% of the time."

That's it. That's all "statistically significant" tells you.

It's a statement about surprise. The data is surprising under the null. So you doubt the null.

What It Does NOT Mean

1. "The effect is large or important."

Nope. Significance tests detect any difference from zero, no matter how tiny. With a large enough sample, even a trivial effect becomes "significant."

Example: You test whether a website redesign increases clicks. You find a 0.1% increase. With 10 million users, that's statistically significant ($p < 0.001$). But it's practically meaningless.

Statistical significance ≠ practical significance.

2. "The null hypothesis is false."

Nope. Even if the null is true, you'll get $p < 0.05$ about 5% of the time—just by chance. That's the false-positive rate.

"Statistically significant" means "probably not random." It doesn't mean "definitely real."

3. "The alternative hypothesis is true."

Nope. Rejecting the null doesn't prove the alternative. It just says the null is implausible. The alternative might be true, or your model might be wrong, or your assumptions might be violated.

4. "There's a 95% probability the result is real."

Nope. The p-value is not the probability the null is false. It's the probability of your data if the null is true. Those are not the same.

We'll unpack this confusion more in the p-value article.

The Replication Crisis: When Significance Tests Break

Here's the uncomfortable truth: the hypothesis testing framework is fragile. It works when used rigorously. It breaks catastrophically when misused.

And it's been systematically misused for decades.

P-Hacking: Torturing the Data Until It Confesses

You run 20 different statistical tests. One gives you $p = 0.04$. You publish that one and ignore the other 19.

The problem: If you run 20 tests, you'd expect 1 to be "significant" just by chance (5% false-positive rate). By selectively reporting, you're inflating the literature with noise.

Forms of p-hacking:

- Trying multiple analyses until one is significant.

- Adding participants until you get significance.

- Removing "outliers" to get significance.

- Testing multiple outcomes and reporting only the significant ones.

None of this is lying, exactly. But it's manipulating the process to get the result you want.

HARKing: Hypothesizing After Results are Known

You collect data. You notice a pattern. You write it up as if you predicted it in advance.

The problem: Hypothesis testing assumes you specified your hypothesis before seeing the data. If you're generating hypotheses from the data, you're circular reasoning.

It's the difference between "I predicted X, tested it, and found X" versus "I found X, so I claim I predicted X."

Publication Bias: The File Drawer Problem

Journals publish "significant" results. They reject "non-significant" results.

So 100 labs test the same thing. 5 get $p < 0.05$ (by chance). 95 don't. The 5 publish. The 95 don't.

The literature now says: "This effect has been replicated 5 times!" But it's just noise.

The result: A literature full of false positives. Effects that don't replicate. Theories built on statistical artifacts.

The Solution: Pre-Registration and Transparency

Pre-register your hypothesis, analysis plan, and sample size before collecting data. That prevents p-hacking and HARKing.

Report all outcomes and all tests, not just the "significant" ones. If you ran 20 tests, say so.

Adjust for multiple comparisons. If you're testing 20 hypotheses, use Bonferroni correction: divide your $\alpha$ by 20. Now you need $p < 0.0025$ to claim significance.

Replicate. One "significant" result is weak evidence. Five independent replications in different labs? That's strong.

Effect Size: What Significance Tests Miss

Hypothesis testing tells you if there's an effect. It doesn't tell you how large.

That's a huge omission.

Example: You test whether a tutoring program increases test scores. You find $p = 0.001$. Highly significant!

But the effect size is +2 points on a 1,000-point test. That's real, but trivial.

Conversely, you test a new cancer drug. You find $p = 0.08$. Not significant.

But the effect size is a 30% reduction in tumor size. That's massive—you just didn't have enough statistical power to detect it.

The solution: Always report effect sizes (Cohen's $d$, $r$, $\eta^2$, odds ratios) alongside p-values.

- Small effect: $d \approx 0.2$

- Medium effect: $d \approx 0.5$

- Large effect: $d \approx 0.8$

A small but significant effect might not matter. A large but non-significant effect might matter a lot—you just need more data.

Power: The Probability of Detecting a Real Effect

Statistical power is the probability that you'll detect an effect if it exists.

Mathematically:

$$\text{Power} = 1 - \beta$$

Where $\beta$ is the probability of a Type II error (false negative—more on that in the next article).

Typical target: 80% power. That means if there's a real effect, you have an 80% chance of detecting it.

What affects power?

- Sample size: Larger samples = higher power.

- Effect size: Larger effects = easier to detect.

- Significance level ($\alpha$): Stricter $\alpha$ = lower power.

- Variability: Less noise = higher power.

The problem: Many studies are underpowered. They have 20% or 30% power. Even if the effect is real, they'll probably miss it.

And if your study is underpowered, "non-significant" results are uninterpretable. You can't tell if there's no effect or if you just lacked power.

The solution: Do a power analysis before collecting data. Calculate the sample size needed to achieve 80% power for your expected effect size.

The Bayesian Alternative: Quantifying Evidence

Frequentist hypothesis testing is binary: reject or don't reject. There's no middle ground.

Bayesian hypothesis testing quantifies the strength of evidence for each hypothesis.

Instead of "reject the null," you calculate a Bayes factor: the ratio of evidence for the alternative vs. the null.

- $\text{BF} = 10$: The alternative is 10× more likely than the null.

- $\text{BF} = 0.1$: The null is 10× more likely than the alternative.

- $\text{BF} = 1$: The data doesn't favor either hypothesis.

This is more intuitive. It tells you how much the evidence tilts toward one hypothesis or the other.

And it lets you accumulate evidence. If one study gives $\text{BF} = 3$ and another gives $\text{BF} = 5$, you multiply: $\text{BF} = 15$. Evidence compounds.

Frequentist p-values don't work that way. You can't combine p-values from multiple studies in any straightforward way.

The catch: Bayesian methods require priors. And priors can be controversial. Frequentist methods avoid that—at the cost of conceptual clarity.

Practical Workflow: How to Test a Hypothesis

Here's the process:

1. Specify your hypothesis before collecting data. Be precise about what you're testing.

2. Choose your test. t-test for comparing means, chi-square for categorical data, ANOVA for multiple groups, etc.

3. Set your significance level. Usually $\alpha = 0.05$, but adjust for context.

4. Do a power analysis. Calculate the sample size needed to detect your expected effect.

5. Collect data. Follow your protocol. Don't stop early just because you got significance.

6. Run the test. Calculate the test statistic and p-value.

7. Report everything. p-value, effect size, confidence interval, sample size, power. Not just "significant" or "not significant."

8. Interpret cautiously. "Significant" doesn't mean "proven." "Non-significant" doesn't mean "no effect."

9. Replicate. One result is a data point. Multiple independent replications are evidence.

The Coherence Connection: Hypothesis Testing as Noise Filtering

Here's the conceptual core.

Hypothesis testing distinguishes signal from noise. It asks: "Is this pattern stable enough to generalize, or is it just random fluctuation?"

In information-theoretic terms, the null hypothesis represents maximum entropy—no structure, no predictability. The alternative represents structure—coherence, pattern, meaning.

A low p-value says: "This data is incompatible with maximum entropy. There's structure here."

And this maps to M = C/T. Meaning arises when patterns persist (coherence over time). Hypothesis testing detects persistence. A "significant" result is a claim that the pattern will replicate—that it's not just noise in this sample.

But here's the catch: significance is not a certificate of truth. It's a probabilistic threshold. A claim that the evidence crosses a line.

And when you lower that line ($\alpha = 0.05$ instead of $0.01$), you get more false positives. When you raise it, you miss real effects.

There's no perfect threshold. It's a trade-off.

What's Next

Hypothesis testing uses p-values as the decision criterion. But p-values are the most misunderstood number in all of science.

Next up: P-Values Explained—what they actually mean, why everyone gets them wrong, and how that breaks science.

Further Reading

- Fisher, R. A. (1925). Statistical Methods for Research Workers. Oliver and Boyd.

- Neyman, J., & Pearson, E. S. (1933). "On the problem of the most efficient tests of statistical hypotheses." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 231(694-706), 289-337.

- Cohen, J. (1994). "The earth is round (p < .05)." American Psychologist, 49(12), 997-1003.

- Ioannidis, J. P. (2005). "Why most published research findings are false." PLoS Medicine, 2(8), e124.

- Wasserstein, R. L., & Lazar, N. A. (2016). "The ASA's statement on p-values." The American Statistician, 70(2), 129-133.

This is Part 6 of the Statistics series, exploring how we extract knowledge from data. Next: "P-Values Explained."

Part 5 of the Statistics series.

Previous: Confidence Intervals: Quantifying Uncertainty in Estimates Next: P-Values: What They Actually Mean

Comments ()