Improper Integrals: When Infinity Gets Involved

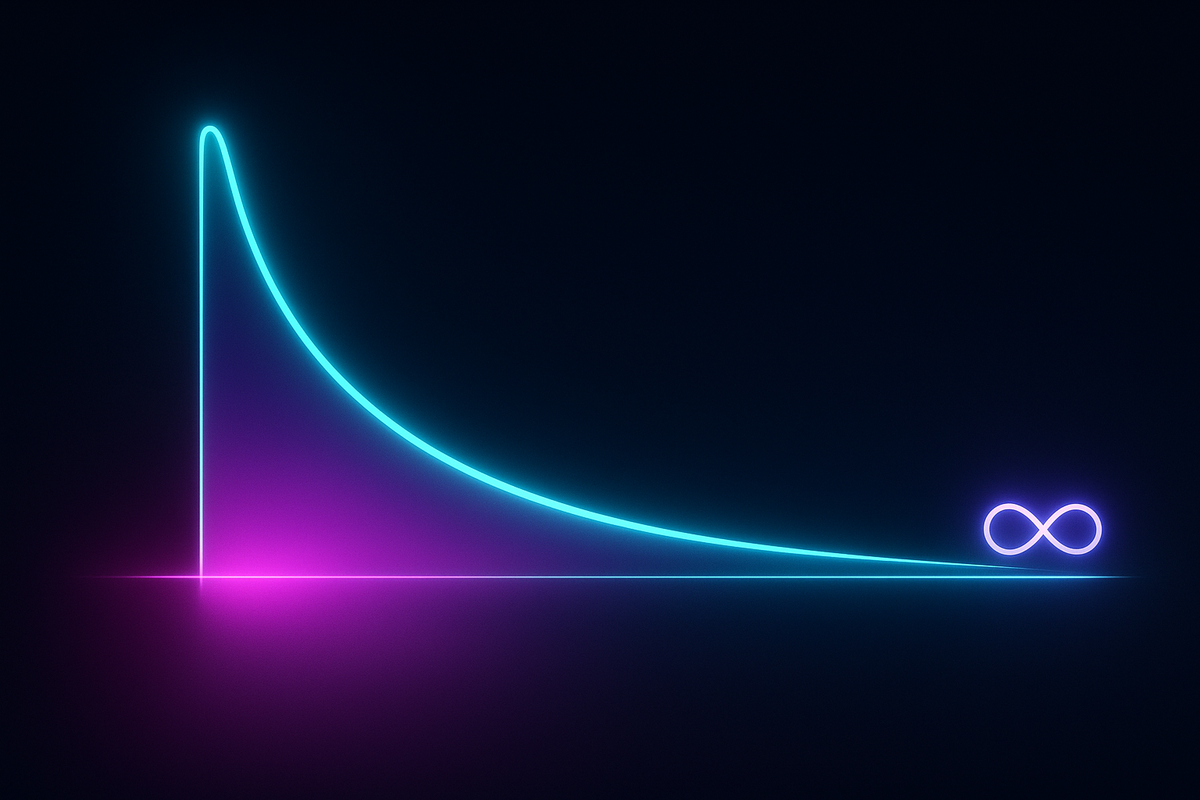

Improper integrals extend integration to cases that seem impossible: infinite intervals or infinite function values.

How can you add up infinitely many things over an infinite range and get a finite answer? Sometimes you can. Sometimes you can't. Improper integrals tell you which.

The trick: replace infinity with a limit.

Two Types of Improper

Type 1: Infinite limits of integration

∫₁^∞ (1/x²) dx — integrating to infinity

∫₋∞^0 eˣ dx — integrating from negative infinity

∫₋∞^∞ e^(-x²) dx — both limits infinite

Type 2: Infinite integrand (vertical asymptote)

∫₀¹ (1/√x) dx — integrand blows up at x = 0

∫₀¹ (1/x) dx — vertical asymptote at x = 0

∫₋₁¹ (1/x²) dx — asymptote inside the interval

Both types require special handling. You can't just plug in infinity.

Type 1: Infinite Bounds

Replace ∞ with a limit.

Definition: ∫ₐ^∞ f(x) dx = lim[t→∞] ∫ₐᵗ f(x) dx

Integrate to a finite bound t, then take the limit as t → ∞.

If the limit exists and is finite, the integral converges. If not, it diverges.

Example: ∫₁^∞ (1/x²) dx

∫₁ᵗ (1/x²) dx = [-1/x]₁ᵗ = -1/t - (-1/1) = 1 - 1/t

As t → ∞: 1 - 1/t → 1

∫₁^∞ (1/x²) dx = 1 — converges.

The infinite region under 1/x² has finite area.

Example: ∫₁^∞ (1/x) dx

∫₁ᵗ (1/x) dx = [ln|x|]₁ᵗ = ln(t) - ln(1) = ln(t)

As t → ∞: ln(t) → ∞

∫₁^∞ (1/x) dx diverges.

The area under 1/x is infinite. Same infinite x-range, but 1/x doesn't shrink fast enough.

The p-Test for Convergence

For ∫₁^∞ (1/xᵖ) dx:

- If p > 1, the integral converges.

- If p ≤ 1, the integral diverges.

This is the threshold. 1/x² (p = 2) converges. 1/x (p = 1) diverges. 1/√x (p = 0.5) diverges even faster.

Think of it as: the function must decay faster than 1/x to have finite area over an infinite interval.

Negative Infinity

For integrals from -∞:

∫₋∞ᵇ f(x) dx = lim[t→-∞] ∫ₜᵇ f(x) dx

Example: ∫₋∞⁰ eˣ dx = lim[t→-∞] [eˣ]ₜ⁰ = 1 - lim[t→-∞] eᵗ = 1 - 0 = 1

The function eˣ decays exponentially as x → -∞, giving finite area.

Both Limits Infinite

Split at any convenient point:

∫₋∞^∞ f(x) dx = ∫₋∞⁰ f(x) dx + ∫₀^∞ f(x) dx

Both parts must converge independently.

Example: ∫₋∞^∞ e^(-x²) dx

This is the famous Gaussian integral. It converges, equaling √π.

The proof uses polar coordinates and is a highlight of multivariable calculus.

Type 2: Vertical Asymptotes

When f(x) → ∞ at a point in [a, b], replace that point with a limit.

Definition: If f blows up at x = a: ∫ₐᵇ f(x) dx = lim[t→a⁺] ∫ₜᵇ f(x) dx

Approach the troublesome point from inside the interval.

Example: ∫₀¹ (1/√x) dx

1/√x → ∞ as x → 0⁺.

∫ₜ¹ x^(-1/2) dx = [2√x]ₜ¹ = 2 - 2√t

As t → 0⁺: 2 - 2√t → 2

∫₀¹ (1/√x) dx = 2 — converges.

Example: ∫₀¹ (1/x) dx

∫ₜ¹ (1/x) dx = [ln|x|]ₜ¹ = 0 - ln(t) = -ln(t)

As t → 0⁺: -ln(t) → ∞

∫₀¹ (1/x) dx diverges.

The function 1/x blows up too fast at 0 for finite area.

p-Test at Zero

For ∫₀¹ (1/xᵖ) dx:

- If p < 1, the integral converges.

- If p ≥ 1, the integral diverges.

This is opposite to the behavior at infinity. Near zero, less singular is better.

Asymptote Inside the Interval

If f has an asymptote at c with a < c < b, split the integral:

∫ₐᵇ f(x) dx = ∫ₐᶜ f(x) dx + ∫ᶜᵇ f(x) dx

Each piece must be evaluated as a limit.

Example: ∫₋₁¹ (1/x²) dx

Split at x = 0: ∫₋₁⁰ (1/x²) dx + ∫₀¹ (1/x²) dx

Each piece diverges (1/x² has p = 2 ≥ 1 at zero).

∫₋₁¹ (1/x²) dx diverges.

Don't be fooled by symmetry. Both pieces are +∞, not canceling.

Comparison Tests

Sometimes you can't evaluate an improper integral explicitly. Comparison helps.

Direct comparison: If 0 ≤ f(x) ≤ g(x) on [a, ∞):

- If ∫ₐ^∞ g(x) dx converges, so does ∫ₐ^∞ f(x) dx.

- If ∫ₐ^∞ f(x) dx diverges, so does ∫ₐ^∞ g(x) dx.

Limit comparison: If lim[x→∞] f(x)/g(x) = L, where 0 < L < ∞:

- f and g either both converge or both diverge.

Example: Does ∫₁^∞ (1/(x² + 1)) dx converge?

Compare to 1/x². For large x: (x² + 1) ≈ x², so 1/(x² + 1) ≈ 1/x².

Since ∫₁^∞ (1/x²) dx converges, so does ∫₁^∞ (1/(x² + 1)) dx.

Common Convergent Forms

Exponential decay: ∫₀^∞ e^(-ax) dx = 1/a (for a > 0)

Gaussian: ∫₋∞^∞ e^(-x²) dx = √π

Rational decay: ∫₁^∞ (1/xᵖ) dx converges for p > 1

Inverse trig type: ∫₀^∞ (1/(1+x²)) dx = π/2

Physical Interpretation

Improper integrals model situations where quantities extend indefinitely:

Total work against a force that decreases with distance (gravity, electrostatics)

Total probability under a probability density function extending to ±∞

Present value of an infinite stream of payments (economics)

Total energy in a wave or field

The convergence question is whether the total is finite — whether the contributions from far away are negligible enough.

The Gabriel's Horn Paradox

The surface generated by rotating y = 1/x (for x ≥ 1) about the x-axis has infinite surface area but finite volume.

Volume: ∫₁^∞ π(1/x)² dx = π ∫₁^∞ (1/x²) dx = π — finite.

Surface area: involves ∫₁^∞ (2π/x)√(1 + 1/x⁴) dx — diverges.

You can fill it with paint but not paint its surface. Infinity is strange.

Summary

Improper integrals extend integration to infinite intervals or infinite integrands.

Method: Replace ∞ or the troublesome point with a variable, integrate normally, take the limit.

Convergence: The limit is finite. Divergence: The limit is ±∞ or doesn't exist.

Key tests:

- 1/xᵖ at ∞: converges if p > 1

- 1/xᵖ at 0: converges if p < 1

- Comparison: bound by known convergent/divergent integrals

Further Reading

- Stewart, J. Calculus. Chapter on improper integrals.

- Apostol, T. Calculus. Rigorous limit treatment.

- Strang, G. Calculus. Free, with applications emphasis.

This is Part 7 of the Integrals series. Next: "Applications of Integration" — volumes, areas, and arc lengths.

Part 7 of the Calculus Integrals series.

Previous: Integration by Parts: The Product Rule in Reverse Next: Applications of Integration: Volume Area and Arc Length

Comments ()