Indefinite Integrals: Finding Antiderivatives

An indefinite integral answers: what function has this as its derivative?

Differentiation is a machine. Put in a function, get out its derivative. Integration is running that machine backward. Put in a derivative, recover the original function.

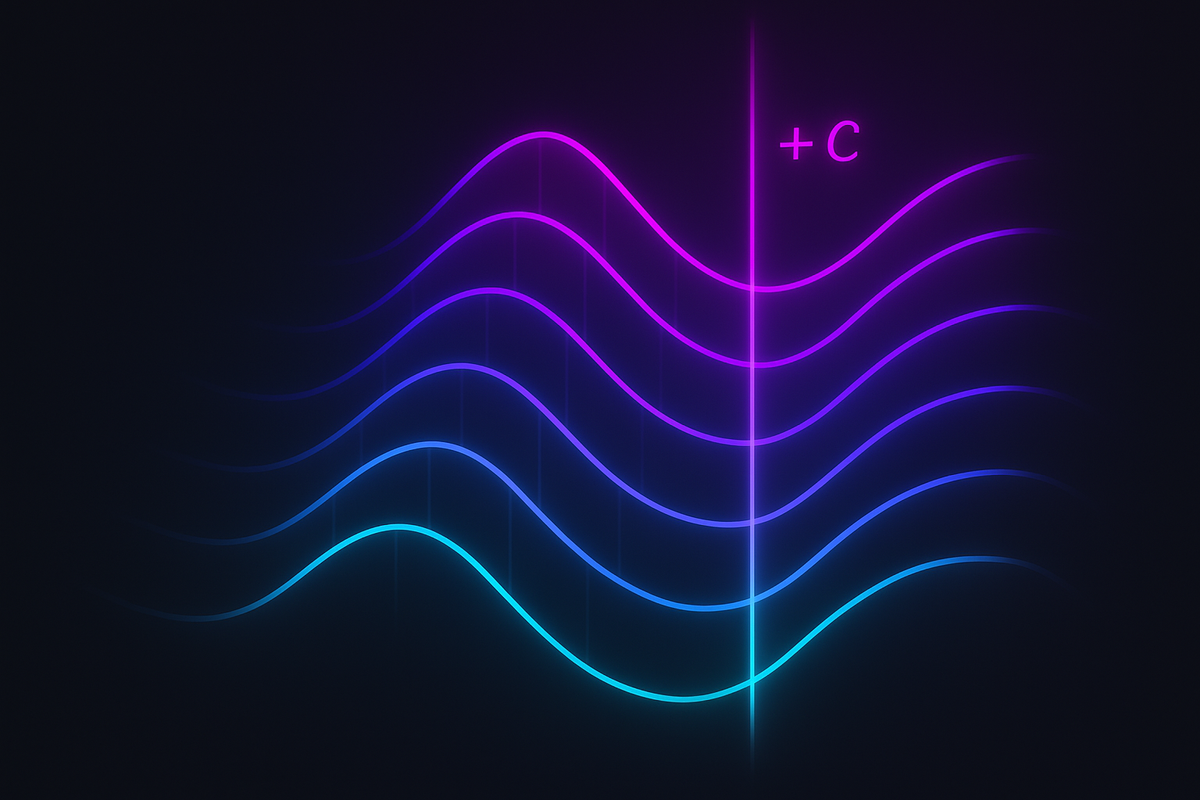

The catch: you don't recover it exactly. You recover a family of functions, all differing by a constant. This is why every indefinite integral has "+ C" at the end.

The Definition

The indefinite integral of f(x) is:

∫ f(x) dx = F(x) + C

where F'(x) = f(x). We call F an antiderivative of f.

Notice: no bounds. That's what makes it "indefinite." We're not computing a specific number — we're finding a general function.

The "+ C" (called the constant of integration) is essential. If F(x) is an antiderivative of f(x), so is F(x) + 7, F(x) - π, F(x) + 42. Adding a constant doesn't change the derivative.

All antiderivatives differ by a constant. That's the complete family.

The Notation

∫ f(x) dx — the integral sign, the integrand f(x), and the differential dx.

Read it as: "the integral of f(x) with respect to x."

The dx indicates we're integrating in the x-direction. This becomes important with multiple variables.

Some write the result as F(x) + C; others omit C as understood. In applications, C often gets determined by initial conditions.

Basic Antiderivatives

These you should know cold:

Power Rule (Reversed): ∫ xⁿ dx = xⁿ⁺¹/(n+1) + C, for n ≠ -1

Example: ∫ x³ dx = x⁴/4 + C

The Exception: ∫ x⁻¹ dx = ∫ 1/x dx = ln|x| + C

Exponentials: ∫ eˣ dx = eˣ + C ∫ aˣ dx = aˣ/ln(a) + C

Trigonometric: ∫ cos(x) dx = sin(x) + C ∫ sin(x) dx = -cos(x) + C ∫ sec²(x) dx = tan(x) + C ∫ csc²(x) dx = -cot(x) + C ∫ sec(x)tan(x) dx = sec(x) + C ∫ csc(x)cot(x) dx = -csc(x) + C

Inverse Trig: ∫ 1/√(1-x²) dx = arcsin(x) + C ∫ 1/(1+x²) dx = arctan(x) + C

Linearity

Integration respects addition and scalar multiplication:

∫ [f(x) + g(x)] dx = ∫ f(x) dx + ∫ g(x) dx

∫ k·f(x) dx = k · ∫ f(x) dx

This means you can integrate term by term and pull out constants.

Example: ∫ (3x² + 5x - 2) dx = 3·∫ x² dx + 5·∫ x dx - 2·∫ 1 dx = 3·(x³/3) + 5·(x²/2) - 2x + C = x³ + (5/2)x² - 2x + C

Note: You only need one + C at the end. Multiple constants combine into one.

Why Integration Is Harder Than Differentiation

Differentiation has algorithms. Given any elementary function, you can systematically compute its derivative using the power rule, product rule, quotient rule, and chain rule. It's mechanical.

Integration has no such algorithm.

Some functions have no elementary antiderivative. The function e^(-x²) is continuous and well-behaved, but its antiderivative cannot be written using standard functions. It's not that we haven't found the answer — it's provably impossible.

Other functions have antiderivatives, but finding them requires creativity. You might need substitution, integration by parts, partial fractions, trigonometric identities, or inspired guesses.

This asymmetry is fundamental. Differentiation simplifies; integration complicates. Going forward is easy; going backward is hard.

Verifying Antiderivatives

Here's the good news: checking is easy.

Claim: ∫ cos(x) dx = sin(x) + C

Check: d/dx [sin(x) + C] = cos(x) ✓

If you're unsure of an antiderivative, differentiate it. If you get back the original integrand, you're correct.

This is why tables of integrals work. You don't need to understand how the antiderivative was found. You just verify it by differentiating.

Initial Value Problems

The constant C becomes specific when you have additional information.

Example: Find f(x) given that f'(x) = 2x and f(1) = 5.

First, find the general antiderivative: f(x) = ∫ 2x dx = x² + C

Then use the initial condition: f(1) = 1² + C = 1 + C = 5 So C = 4.

Therefore f(x) = x² + 4.

This is the pattern: integrate to get a family, use conditions to select one member.

Common Mistakes

Forgetting + C: ∫ x dx = x²/2 is incomplete. ∫ x dx = x²/2 + C is correct.

This matters when applying initial conditions or in differential equations.

Wrong power rule exponent: ∫ x³ dx = x⁴/4, not x⁴/3.

The new exponent is n+1, and you divide by n+1.

Sign errors with trig: ∫ sin(x) dx = -cos(x) + C, not +cos(x). ∫ cos(x) dx = sin(x) + C, not -sin(x).

Check by differentiating: d/dx[-cos(x)] = sin(x) ✓

Integrating products incorrectly: ∫ x · eˣ dx ≠ (x²/2) · eˣ

You can't integrate factors separately. Products require integration by parts.

Building Intuition

Think of differentiation as erosion. Functions become simpler, lower-degree, more refined.

Integration is the reverse — building up. You're reconstructing what erosion wore away.

But you can't uniquely reconstruct from eroded evidence. The constant C represents what was lost — any constant erodes to zero, leaving no trace.

This is why initial conditions matter. They're the archaeological clues that let you recover the specific function, not just its family.

The Practical Point

Indefinite integrals are the tool for solving definite integrals efficiently.

By the Fundamental Theorem, once you have F(x) = ∫ f(x) dx:

∫ₐᵇ f(x) dx = F(b) - F(a)

The C cancels: [F(b) + C] - [F(a) + C] = F(b) - F(a).

So for definite integrals, the constant doesn't matter. But for differential equations and initial value problems, it's essential.

A Taste of Techniques

We'll cover these fully in later articles, but here's the preview:

Substitution (u-sub): For integrands that look like f(g(x))·g'(x), substitute u = g(x).

Integration by parts: For products like x·eˣ, use ∫ u dv = uv - ∫ v du.

Partial fractions: For rational functions, decompose into simpler fractions.

Trigonometric identities: For powers of sin and cos, use identities to simplify.

Trigonometric substitution: For square roots like √(1-x²), substitute x = sin(θ).

Each technique reverses a differentiation pattern. Substitution reverses the chain rule. Integration by parts reverses the product rule.

Further Reading

- Stewart, J. Calculus: Early Transcendentals. Comprehensive table of integrals.

- Zwillinger, D. CRC Standard Mathematical Tables. Extensive integral tables.

- Wolfram Alpha — computer algebra for checking antiderivatives.

This is Part 3 of the Integrals series. Next: "Definite Integrals" — computing actual areas and numbers.

Part 3 of the Calculus Integrals series.

Previous: The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus: Derivatives and Integrals Are Opposites Next: Definite Integrals: Computing Actual Areas

Comments ()