Infinite Series: When Sums Never Stop but Still Converge

You can add infinitely many numbers and get a finite answer.

This sounds impossible. Adding more should always give you more. But watch:

1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + ...

Each term is half the previous. The partial sums creep toward 1 but never exceed it:

- S₁ = 0.5

- S₂ = 0.75

- S₃ = 0.875

- S₄ = 0.9375

- S₁₀ ≈ 0.999

The infinite sum equals exactly 1.

This is the central miracle of infinite series: some infinite additions converge to finite values. The question isn't whether infinite sums exist—it's which infinite sums have finite answers.

What Convergence Means

An infinite series ∑aₖ converges if its partial sums approach a limit.

Define partial sums: Sₙ = a₁ + a₂ + ... + aₙ

If lim(n→∞) Sₙ = L exists and is finite, the series converges to L.

If the limit doesn't exist (blows up, oscillates, etc.), the series diverges.

Convergence is about the sequence of partial sums, not the sequence of terms.

The terms can shrink toward zero (necessary but not sufficient). The partial sums must stabilize at a finite value (the actual condition).

Necessary Condition: Terms Must Shrink

If ∑aₖ converges, then aₖ → 0 as k → ∞.

Proof intuition: If terms don't shrink, adding infinitely many of them must blow up.

But the converse is false. Terms shrinking to zero doesn't guarantee convergence.

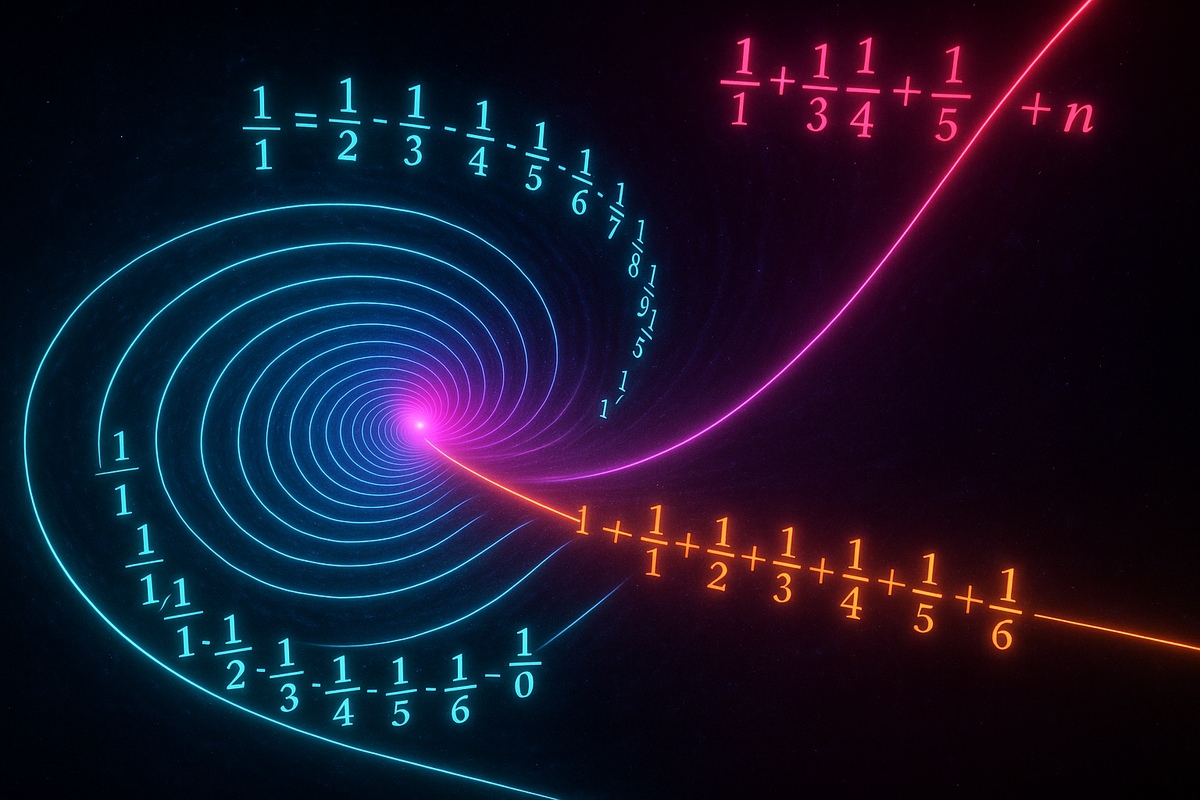

The harmonic series 1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/4 + ... has terms approaching 0, but diverges.

This is the trap. "The terms get small" feels like it should be enough. It's not.

The Harmonic Series: A Famous Divergence

1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/4 + 1/5 + ... = ∞

The terms shrink, but not fast enough. Here's why:

Group the terms:

- First group: 1

- Second group: 1/2

- Third group: 1/3 + 1/4 > 1/4 + 1/4 = 1/2

- Fourth group: 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/7 + 1/8 > 4 × (1/8) = 1/2

- Fifth group: 1/9 + ... + 1/16 > 8 × (1/16) = 1/2

Each group adds at least 1/2. There are infinitely many groups. The sum exceeds any bound.

The harmonic series grows—slowly, but without limit. After 10 million terms, the sum is only about 16.7. After a googol terms, it's only about 230. But it never stops growing.

The p-Series Test

The series ∑1/kᵖ converges if and only if p > 1.

| p | Series | Converges? |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | ∑1/√k | No |

| 1 | ∑1/k | No (harmonic) |

| 1.001 | ∑1/k^1.001 | Yes |

| 2 | ∑1/k² | Yes (= π²/6) |

| 3 | ∑1/k³ | Yes |

The threshold is p = 1. Just barely faster than 1/k is enough to converge. Just barely slower diverges.

The series ∑1/k² = 1 + 1/4 + 1/9 + 1/16 + ... = π²/6 ≈ 1.645.

This connection to π is surprising and beautiful—one of Euler's famous discoveries.

Geometric Series: The Prototype

The geometric series ∑rᵏ converges if |r| < 1.

Sum: ∑ₖ₌₀^∞ rᵏ = 1/(1-r)

When |r| < 1, each term shrinks exponentially. The sum stays bounded.

When |r| ≥ 1, terms don't shrink (or grow), and the series diverges.

Geometric series are the benchmark. Other series are often analyzed by comparison to geometric series.

Absolute Convergence

A series converges absolutely if ∑|aₖ| converges.

If a series converges absolutely, it converges (in the regular sense).

The converse isn't true. Conditional convergence means the series converges, but not absolutely.

Example: The alternating harmonic series

1 - 1/2 + 1/3 - 1/4 + 1/5 - ... = ln(2)

This converges (to ln 2 ≈ 0.693). But the absolute values 1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + ... diverge.

The alternating series converges only because positive and negative terms partially cancel.

Why Absolute Convergence Matters

Absolutely convergent series are well-behaved:

- You can rearrange terms without changing the sum

- You can multiply series term by term

- The sum is independent of grouping

Conditionally convergent series are fragile:

- Rearranging terms can change the sum

- In fact, the Riemann rearrangement theorem says you can rearrange a conditionally convergent series to sum to any value you want

This is strange but true. The alternating harmonic series sums to ln(2), but by cleverly reordering its terms, you can make it sum to 17, or π, or -∞.

Absolute convergence is the "safe" kind. Conditional convergence requires care.

The Ratio and Root Tests

For series with factorial or exponential terms, these tests often work:

Ratio Test: Compute L = lim |aₙ₊₁/aₙ|.

- If L < 1: converges absolutely

- If L > 1: diverges

- If L = 1: inconclusive

Root Test: Compute L = lim |aₙ|^(1/n).

- If L < 1: converges absolutely

- If L > 1: diverges

- If L = 1: inconclusive

These tests compare the series to geometric series. If the ratio or root is less than 1, the terms shrink faster than a convergent geometric series.

Example: ∑n!/nⁿ

Use ratio test: aₙ₊₁/aₙ = [(n+1)!/(n+1)ⁿ⁺¹] / [n!/nⁿ] = ... → 1/e < 1.

The series converges.

Partial Sums vs. Total Sum

Even when we know a series converges, finding the exact sum is often hard.

We know ∑1/k² = π²/6 (Euler proved this). We know ∑1/k³ ≈ 1.202 (but no nice closed form). We know ∑1/k⁴ = π⁴/90. We don't know ∑1/k⁵ in terms of known constants.

Convergence is one question. Finding the sum is another, often harder question.

Practically, we approximate infinite sums by computing partial sums. If Sₙ ≈ S∞ for large n, we use Sₙ as an estimate.

The Alternating Series Test

For alternating series ∑(-1)ⁿaₙ with aₙ > 0:

If aₙ is decreasing and aₙ → 0, then the series converges.

Moreover, the error is bounded: |S - Sₙ| < aₙ₊₁.

This is a powerful test. It says alternating series with shrinking terms converge, and gives an error bound for free.

Example: 1 - 1/2 + 1/3 - 1/4 + ...

Terms 1/n shrink to 0. The series converges. After 100 terms, the error is less than 1/101 ≈ 0.01.

Zeno's Paradox Resolved

Zeno argued: To walk across a room, you must first go half the distance, then half of what remains, then half of that, ad infinitum. You must complete infinitely many tasks, which is impossible.

Series response: 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + ... = 1.

The infinite tasks sum to a finite distance. You cross the room because an infinite series can have a finite sum.

Zeno's paradox isn't a paradox—it's a demonstration that infinite sums exist.

Why Infinite Series Matter

- They extend arithmetic. Addition isn't limited to finite lists. Infinite addition makes sense when it converges.

- They approximate functions. Taylor series express functions as infinite polynomials. sin(x) = x - x³/6 + x⁵/120 - ...

- They connect to calculus. Integration is the limit of Riemann sums. Infinite sums are the discrete analog.

- They appear everywhere. Probability, physics, engineering, computer science—anywhere patterns accumulate infinitely.

- They require care. Not all infinite sums converge. The ones that do follow rules worth knowing.

The infinite series teaches: infinity isn't always infinite. Sometimes, adding forever gives you a finite answer.

Part 8 of the Sequences Series series.

Previous: Geometric Series: Summing Geometric Sequences Next: Convergence Tests: When Does an Infinite Series Have a Sum?

Comments ()