Applications of Integration: Volume Area and Arc Length

Integrals do more than find areas under curves. They calculate volumes of 3D objects, surface areas, arc lengths, work done by forces, and more.

The principle is always the same: slice the problem into infinitesimal pieces, set up an integral, and add them up.

This is calculus at its most practical.

Area Between Curves

To find the area between two curves f(x) and g(x) from a to b:

A = ∫ₐᵇ |f(x) - g(x)| dx

If f(x) ≥ g(x) throughout:

A = ∫ₐᵇ [f(x) - g(x)] dx

Top curve minus bottom curve, integrated.

Example: Area between y = x² and y = x from x = 0 to x = 1.

The line y = x is above y = x² on [0, 1].

A = ∫₀¹ (x - x²) dx = [x²/2 - x³/3]₀¹ = (1/2 - 1/3) - 0 = 1/6

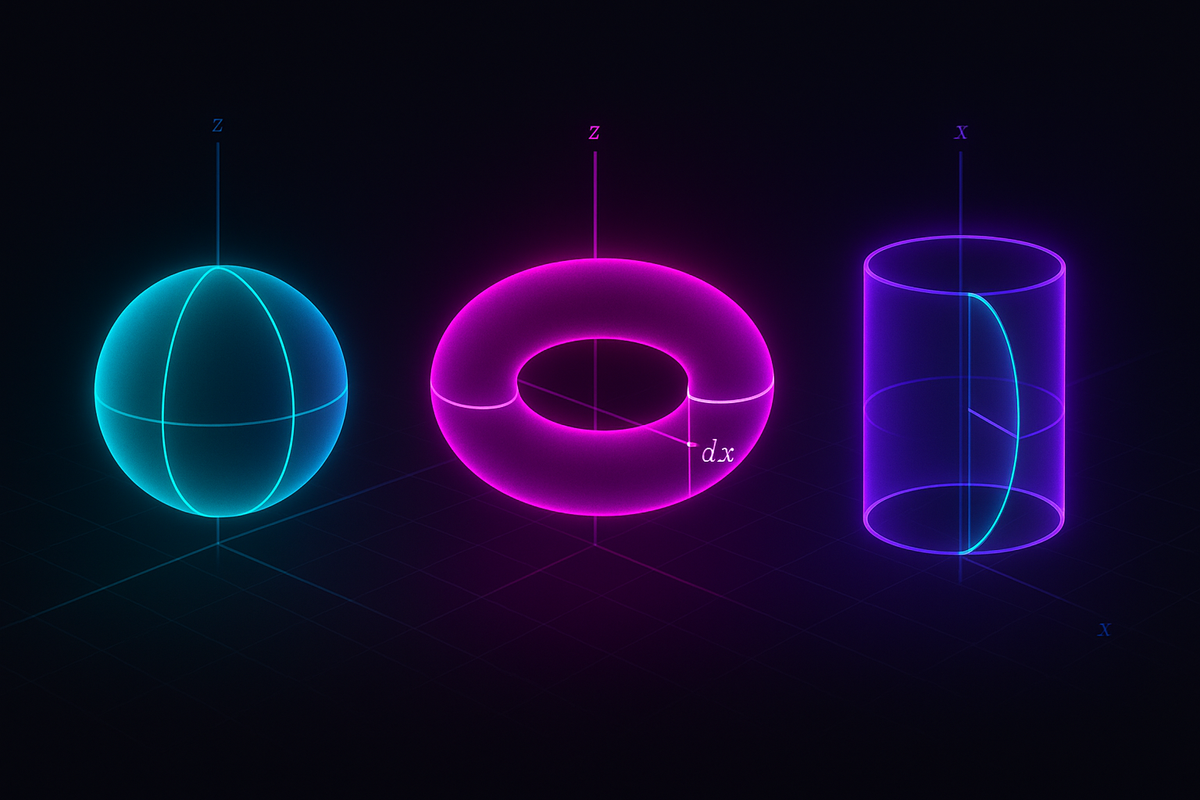

Volume by Disks

Rotate a region around an axis to create a 3D solid. Find its volume by slicing into thin disks.

Each disk has radius r(x) and thickness dx. Its volume is πr²·dx.

V = ∫ₐᵇ π[r(x)]² dx

Example: Rotate y = √x from x = 0 to x = 4 around the x-axis.

The radius at x is r(x) = √x.

V = ∫₀⁴ π(√x)² dx = π ∫₀⁴ x dx = π[x²/2]₀⁴ = π(8 - 0) = 8π

Volume by Washers

When the region is between two curves, disks become washers (donuts).

Outer radius R(x), inner radius r(x):

V = ∫ₐᵇ π[R(x)² - r(x)²] dx

Example: Rotate the region between y = x² and y = x around the x-axis.

Outer radius: R(x) = x (the line) Inner radius: r(x) = x² (the parabola)

V = π ∫₀¹ (x² - x⁴) dx = π[x³/3 - x⁵/5]₀¹ = π(1/3 - 1/5) = 2π/15

Volume by Shells

Sometimes it's easier to use cylindrical shells instead of disks.

Rotate around the y-axis. A shell at x has radius x, height f(x), and thickness dx.

V = ∫ₐᵇ 2πx · f(x) dx

Example: Rotate y = x² (from x = 0 to x = 1) around the y-axis.

V = ∫₀¹ 2πx · x² dx = 2π ∫₀¹ x³ dx = 2π[x⁴/4]₀¹ = 2π(1/4) = π/2

When to use shells vs. disks:

- Disks: slice perpendicular to axis of rotation

- Shells: slice parallel to axis of rotation

Choose whichever gives simpler integrands.

Arc Length

The length of a curve y = f(x) from x = a to x = b:

L = ∫ₐᵇ √(1 + [f'(x)]²) dx

This formula comes from the Pythagorean theorem applied to infinitesimal segments.

Example: Arc length of y = x^(3/2) from x = 0 to x = 4.

f'(x) = (3/2)x^(1/2) [f'(x)]² = (9/4)x

L = ∫₀⁴ √(1 + 9x/4) dx

Let u = 1 + 9x/4, then du = (9/4)dx:

L = (4/9) ∫₁¹⁰ √u du = (4/9) · (2/3)u^(3/2)|₁¹⁰ = (8/27)(10^(3/2) - 1) = (8/27)(10√10 - 1) ≈ 9.07

Arc length integrals are often ugly. Numerical methods are common.

Surface Area of Revolution

Rotate a curve y = f(x) around the x-axis. The surface area is:

S = ∫ₐᵇ 2πf(x) √(1 + [f'(x)]²) dx

It's the arc length formula, weighted by the circumference at each point.

Example: Surface area from rotating y = √x from x = 0 to x = 1 around the x-axis.

f(x) = √x, f'(x) = 1/(2√x), [f'(x)]² = 1/(4x)

S = 2π ∫₀¹ √x · √(1 + 1/(4x)) dx = 2π ∫₀¹ √(x + 1/4) dx

= 2π · (2/3)(x + 1/4)^(3/2)|₀¹ = (4π/3)[(5/4)^(3/2) - (1/4)^(3/2)] = (4π/3)[5√5/8 - 1/8] = (π/6)(5√5 - 1)

Work

Work = Force × Distance, but only when force is constant.

When force F(x) varies with position:

W = ∫ₐᵇ F(x) dx

Example: Spring with F(x) = kx (Hooke's law). Work to stretch from x = 0 to x = d:

W = ∫₀ᵈ kx dx = k[x²/2]₀ᵈ = kd²/2

Example: Lifting a leaky bucket. A 50 lb bucket loses water at 0.5 lb/ft as it's raised 20 ft.

Weight at height x: W(x) = 50 - 0.5x

Work = ∫₀²⁰ (50 - 0.5x) dx = [50x - 0.25x²]₀²⁰ = 1000 - 100 = 900 ft-lb

Hydrostatic Pressure

Fluid pressure increases with depth. The force on a submerged surface:

F = ∫ ρgh · w(h) dh

where ρ = fluid density, g = gravity, h = depth, w(h) = width at depth h.

Example: Force on a vertical dam face, 10 m wide, 5 m deep in water (ρ = 1000 kg/m³).

At depth h, pressure = ρgh. The strip at depth h has width 10 m and thickness dh.

F = ∫₀⁵ (1000)(9.8)(h)(10) dh = 98000 ∫₀⁵ h dh = 98000 · [h²/2]₀⁵ = 98000 · 12.5 = 1,225,000 N (about 1.2 MN)

Center of Mass

For a thin plate with density δ(x) along a line from a to b:

Mass: M = ∫ₐᵇ δ(x) dx

Moment about origin: Mₓ = ∫ₐᵇ x · δ(x) dx

Center of mass: x̄ = Mₓ / M

For uniform density, this simplifies to the centroid — the geometric center.

Example: Centroid of the region under y = x² from 0 to 1.

x̄ = (∫₀¹ x · x² dx) / (∫₀¹ x² dx) = (∫₀¹ x³ dx) / (∫₀¹ x² dx) = [x⁴/4]₀¹ / [x³/3]₀¹ = (1/4) / (1/3) = 3/4

Probability

For a continuous probability density function p(x):

Probability that X is between a and b: P(a ≤ X ≤ b) = ∫ₐᵇ p(x) dx

Total probability: ∫₋∞^∞ p(x) dx = 1

Expected value: E[X] = ∫₋∞^∞ x · p(x) dx

The integral is how continuous probability works.

The Unifying Theme

All these applications follow one pattern:

- Slice the problem into small pieces

- Approximate each piece (area, volume, work, etc.)

- Set up the integral — the sum of infinitesimal contributions

- Integrate — calculus handles the infinite sum

Whether you're computing volume, work, arc length, or probability, the structure is identical. Change the formula for each piece; the integration concept stays the same.

Summary

- Area between curves: ∫[top - bottom] dx

- Volume (disks): ∫ πr² dx

- Volume (washers): ∫ π(R² - r²) dx

- Volume (shells): ∫ 2πrh dx

- Arc length: ∫ √(1 + [f']²) dx

- Surface area: ∫ 2πf √(1 + [f']²) dx

- Work: ∫ F(x) dx

The integral is the universal tool for accumulation. Learn the setup for each application; the calculus is always the same.

Further Reading

- Stewart, J. Calculus. Extensive applications chapter.

- Thomas & Finney. Calculus. Many worked examples.

- MIT OpenCourseWare 18.01 — Applications of integration lectures.

This is Part 8 of the Integrals series. Next: "Differential Equations: Introduction" — when derivatives and functions mix.

Part 8 of the Calculus Integrals series.

Previous: Improper Integrals: When Infinity Gets Involved Next: Differential Equations: When Derivatives and Functions Mix

Comments ()