Seeing Like a State: Why Institutions Fail

In 1985, the Soviet Union was the world's largest wheat producer. By 1991, the country that had fed itself for decades couldn't keep bread on the shelves. What happened wasn't a drought or a plague. It was an information problem—and understanding it explains why large institutions fail in predictable ways.

James C. Scott's Seeing Like a State (1998) is the essential text on this failure mode. Scott was a political scientist who studied why grand development schemes—from Soviet collectivization to Tanzanian village consolidation to Brasília's modernist urban planning—kept failing in similar ways. The answer wasn't corruption or incompetence. It was legibility.

The Legibility Problem

States need to see their populations. They need to know how many people live where, what they produce, what they own. Without this information, you can't tax, conscript, or administer.

But traditional societies weren't organized for state visibility. They used local naming conventions that made no sense to outsiders. They measured land in inconsistent local units. They organized production in ways that reflected local knowledge—knowledge that couldn't be transmitted to distant bureaucracies.

Consider something as basic as names. In many traditional societies, names were contextual—you might be called one thing by your family, another by your village, another depending on your life stage. From the state's perspective, this is chaos. How do you track a person across time and space if their name keeps changing?

The state's response: simplification. Create fixed surnames. Standardize land measurement. Impose grid patterns on irregular settlements. Replace complex polycultures with monoculture plantations. Make the illegible legible.

The surname is a perfect example. States imposed permanent, hereditary family names—not because they better reflected social reality, but because they made populations trackable. The same person who moved, married, or changed status could now be followed through records. The simplification served the state's administrative needs, not the individual's identity.

The problem: legibility comes at a cost. The simplifications that make societies visible to states also destroy the local knowledge that made them function.

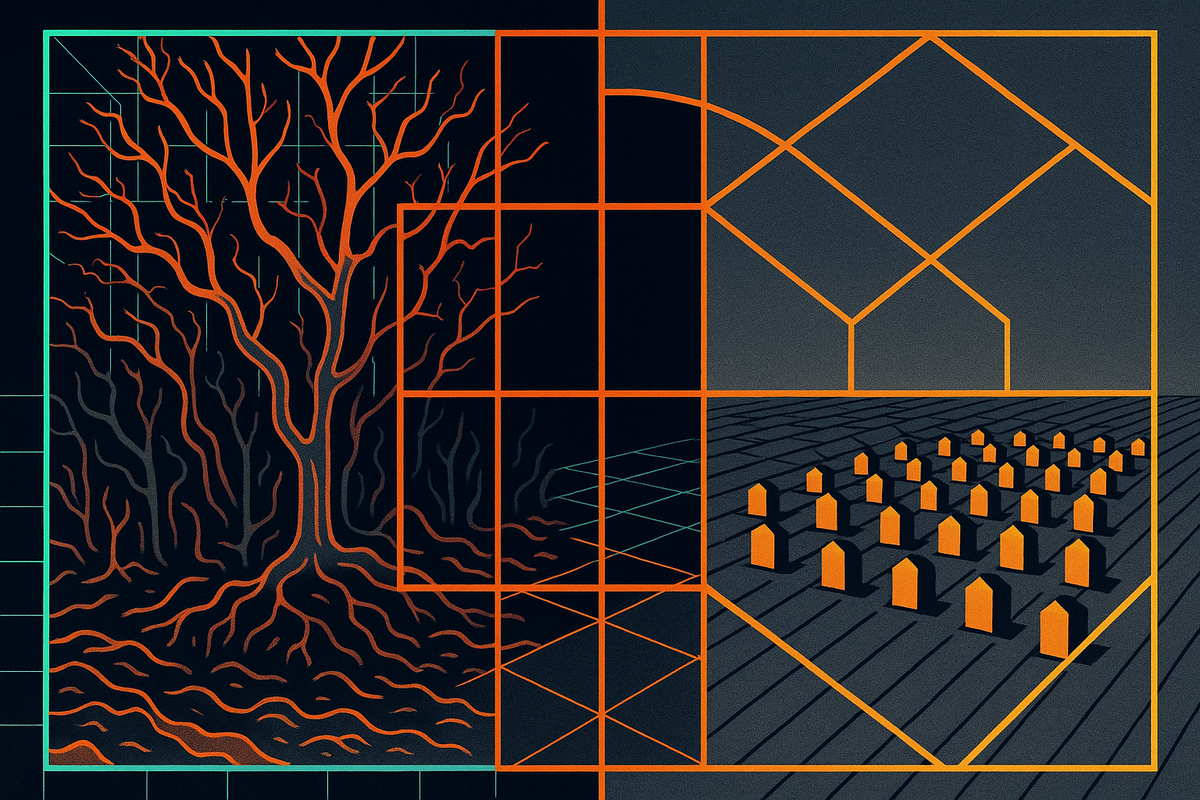

A forest managed by a village for centuries—providing timber, fuel, fodder, medicine, spiritual meaning—gets replaced by a "scientific" plantation of a single tree species in regular rows. The plantation is legible: you can calculate board feet, plan harvests, project yields. But the rich ecology is gone. The diverse uses are eliminated. And when disease hits the monoculture, there's no resilience. The German forestry term for this is Waldsterben—forest death. It happened.

What states see is not what exists. The map is not the territory—but the state starts treating the map as if it were.

High Modernism

Scott coins the term high modernism for the ideology that drove the worst failures. High modernism is the belief that society can be rationally designed from the top down by experts using scientific principles.

Key features:

Administrative ordering of nature and society. Complex realities must be simplified into categories the state can work with. This isn't just practical convenience—it becomes an ideology. The simplified version is considered superior to the messy reality.

Visual aesthetic of order. Straight lines, right angles, geometric regularity. High modernist planners genuinely believed that order was beautiful and that disorder was pathology. Le Corbusier wanted to demolish central Paris and replace it with towers in a grid.

Belief in scientific progress. Experts know best. Traditional practices are backward. Modern science can redesign everything better.

Authoritarian implementation. You can't build utopia with democratic consent, because people cling to their old ways. You need a strong state willing to impose the plan.

Scott's canonical examples of high modernist failure:

Soviet collectivization. Replace millions of peasant farms, each adapted to local conditions over generations, with centrally planned collective farms using "scientific" methods. Result: famine.

Tanzanian villagization. Move scattered rural populations into planned villages with modern layouts and services. Result: collapsed production, mass hardship, eventual abandonment.

Brasília. Build a new capital city from scratch according to modernist principles. Result: a city that works badly for the people who actually live in it.

Scientific forestry. Replace diverse forests with monoculture plantations. Result: initial high yields followed by ecological collapse.

The pattern is consistent: experts design systems based on abstract models, impose them on complex realities, and watch them fail.

Mētis: The Knowledge That Can't Be Transmitted

Scott's key concept is mētis—the Greek word for practical wisdom, cunning, experiential knowledge. It's the kind of knowledge you can only acquire through doing.

A farmer knows when to plant not from reading a calendar but from observing the soil, the weather, the plants themselves. A fisherman knows where the fish are from decades of experience on specific waters. A craftsman knows how materials behave from years of working with them.

Mētis is local, embodied, and difficult to articulate. You can't fully transmit it in a manual. It develops over time through practice. It's adapted to specific contexts.

High modernism treats mētis as primitive—an inferior substitute for scientific knowledge. The expert with formal training is assumed to know better than the practitioner with experiential knowledge.

But mētis often captures information that formal knowledge misses. The peasant's polyculture might look inefficient compared to the agronomist's monoculture—until you factor in resilience, sustainability, and the full range of products. The traditional practice might be "irrational" only because the observer doesn't understand what it's actually optimizing for.

When states override mētis with scientific planning, they often destroy the knowledge that made systems work. And because mētis is local and embodied, once it's gone, it's very hard to recover.

The Four Elements of Failure

Scott identifies four conditions that combine to produce catastrophic planning failures:

1. Administrative ordering. The state simplifies complex realities into legible categories. This is sometimes necessary but always distorting.

2. High modernist ideology. The belief that scientific expertise can design systems better than evolved practice. The aesthetic preference for order over messiness.

3. Authoritarian state capacity. The power to actually implement plans over resistance. Democratic states can have high modernist visions too—but they can't usually impose them fully.

4. Prostrate civil society. A population unable to resist. Wars, revolutions, colonialism create conditions where traditional structures collapse and states can impose designs.

All four are necessary for catastrophe. High modernism without state capacity is just daydreaming. State capacity without high modernism doesn't impose schemes on resistant realities. Civil society that can push back limits the damage.

The worst failures—Soviet collectivization, Maoist China, colonial development projects—combined all four.

The Practical Order

Scott's alternative isn't anti-planning. It's understanding the limits of planning.

Complex systems develop practical orders that aren't visible from above. A city neighborhood that looks chaotic from the urban planner's perspective might actually be highly ordered—organized around relationships, uses, and adaptations that the planner can't see.

Jane Jacobs made this argument for cities in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. The "disorder" of mixed-use neighborhoods—shops, residences, small workshops, street life—actually produces safety, economic vitality, and community. The "order" of high modernist housing projects—separated uses, car-oriented design, legible grids—produces crime, isolation, and decay.

The practical order works because it evolved. It wasn't designed from above; it developed from below, through countless small adaptations by people solving real problems. It encodes information that no planner could collect.

This doesn't mean change is impossible. It means change should be incremental, reversible, and responsive to feedback. Build small, test, adjust. Don't demolish and replace.

Contemporary Applications

Scott was writing about 20th-century development projects. But the pattern recurs constantly.

Platform moderation. Social media platforms create simplified categories—hate speech, misinformation, harassment—and try to enforce them algorithmically at scale. But the categories don't capture the contextual nuances that determine what speech actually means in specific communities. Ironic usage, community-specific language, counter-speech that quotes the original—all get flattened by the simplification. The result: inconsistent enforcement, over-moderation of marginalized groups, under-moderation of sophisticated bad actors.

The platform's need for legibility—for categories that can be applied consistently at billion-user scale—systematically destroys the context that determines meaning.

Metric-driven management. When organizations manage by measurable targets, people optimize for the targets rather than the underlying goals. Campbell's Law: any quantitative measure used for decision-making becomes corrupted. The metrics are legible to management; the actual work is not.

This is why hospitals game wait time statistics while actual care suffers. Why police departments juice arrest numbers while crime continues. Why schools teach to tests while education deteriorates. The legible measure replaces the illegible reality it was supposed to represent.

EdTech standardization. Replace the mētis of experienced teachers with standardized curricula delivered digitally. The variation of good teaching—adaptation to individual students, responsiveness to context—is illegible to the system. What's measurable (test scores, engagement metrics) becomes what matters.

Algorithmic decision-making. Credit scores, risk assessments, recommendation systems—all simplify complex realities into legible numbers. The simplifications work on average but fail on edge cases, and the failures systematically harm certain groups. Someone who paid rent on time for decades but never had a credit card is "invisible" to the credit system. The complexity of their financial life is illegible.

High modernism didn't end with the 20th century. It migrated into new forms. The utopian impulse—the belief that experts with the right data can redesign systems from above—is alive in every "disruption" narrative, every AI-will-fix-everything claim, every move-fast-and-break-things manifesto.

What This Means

Scott's analysis offers several lessons:

Beware of legibility's costs. Making things visible to institutions requires simplification. Simplification destroys information. The more legible your system, the more you've lost.

Respect mētis. The people doing the work often know things that management doesn't. Experienced practitioners have embodied knowledge that can't be formalized. Top-down redesigns that ignore this knowledge will fail.

Favor incrementalism. Big plans fail big. Small experiments can be corrected. The question isn't whether to change but how—and the answer is usually slower and more cautiously than planners prefer.

Civil society matters. The ability to push back on bad plans is essential. Authoritarian implementation of good ideas still usually produces bad outcomes.

The view from nowhere is a lie. There is no neutral perspective from which complex systems can be comprehensively understood. All perspectives are partial. Humility about what we can know should inform how we act.

The Takeaway

States need legibility to function. But the simplifications that produce legibility also destroy the local knowledge that makes systems work.

High modernism—the belief that experts can redesign society scientifically from above—consistently produces catastrophic failures when combined with authoritarian power and prostrate civil society.

The alternative isn't no planning but humble planning. Respect for mētis. Incremental change. Reversibility. Responsiveness to feedback.

Every large institution—government, corporation, platform—faces the legibility problem. Understanding it won't make it go away. But it might prevent you from demolishing working systems in pursuit of beautiful blueprints that only work on paper.

Further Reading

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press. - Scott, J. C. (2017). Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. Yale University Press. - Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House.

This is Part 3 of the Anthropology of Institutions series. Next: "Debt: The First 5,000 Years"

Comments ()