Least Common Multiple: When Cycles Align

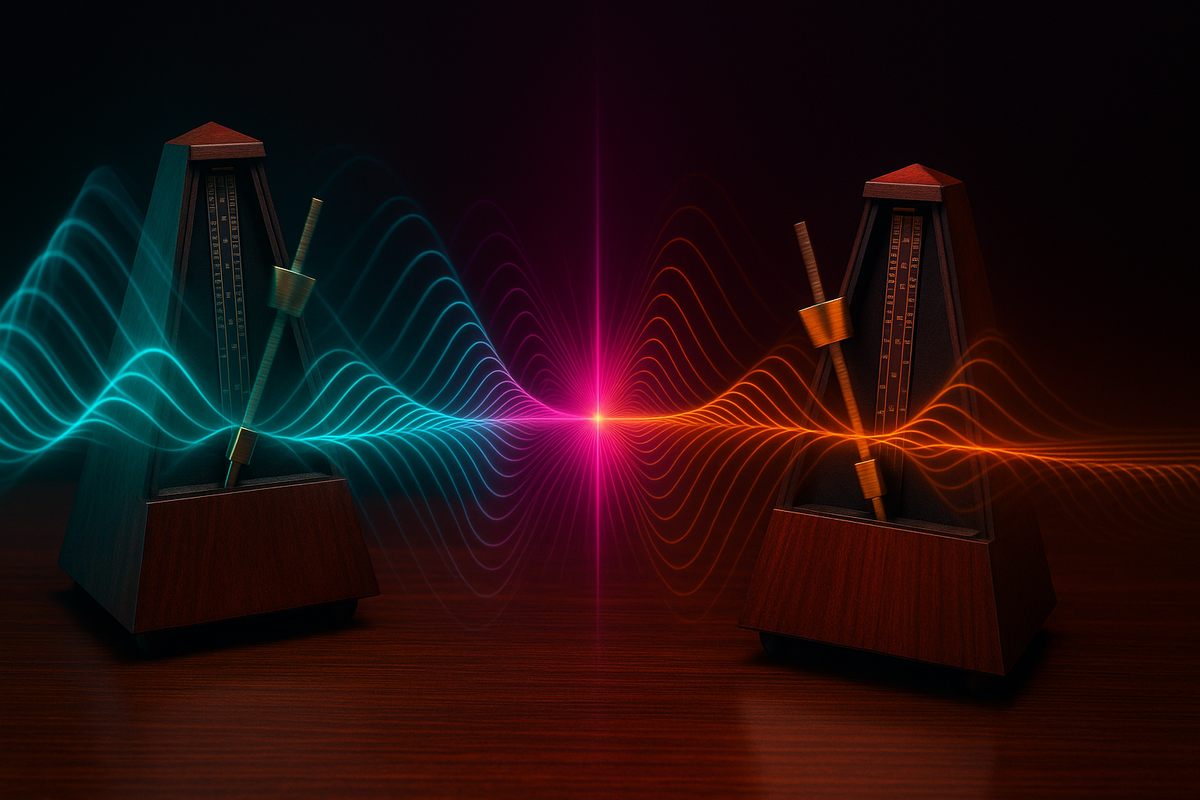

The LCM is the first place two cycles meet again.

Imagine a light that blinks every 4 seconds and another that blinks every 6 seconds. They start together. When do they blink together again? At 12 seconds — the smallest number divisible by both 4 and 6.

The LCM is where separate rhythms synchronize.

That's the unlock. lcm(4, 6) = 12 isn't just abstract arithmetic — it's when two independent cycles realign. Adding fractions with different denominators? You need a common denominator: the LCM. Scheduling events that repeat at different intervals? Their coincidence follows the LCM.

The Definition

The least common multiple of a and b, written lcm(a, b), is the smallest positive integer divisible by both a and b.

Equivalently: lcm(a, b) is the smallest m such that a | m and b | m.

Examples

lcm(4, 6) = 12 (smallest number divisible by 4 and by 6) lcm(3, 5) = 15 (smallest number divisible by 3 and by 5) lcm(6, 8) = 24 lcm(12, 18) = 36

Finding LCM by Factorization

Factor both numbers. Take the maximum power of each prime.

lcm(360, 150): 360 = 2³ × 3² × 5 150 = 2 × 3 × 5²

All primes: 2, 3, 5 Maximum powers: 2³, 3², 5²

lcm(360, 150) = 8 × 9 × 25 = 1800

Compare with GCD (which takes minimums): gcd(360, 150) = 30.

LCM from GCD

The shortcut formula:

lcm(a, b) = (a × b) / gcd(a, b)

Example: lcm(12, 18) gcd(12, 18) = 6 lcm(12, 18) = (12 × 18) / 6 = 216 / 6 = 36

This formula is computationally efficient — use Euclid's algorithm for GCD, then one multiplication and division.

Why the Formula Works

Every common multiple of a and b is a multiple of lcm(a, b). And: gcd(a, b) × lcm(a, b) = a × b.

Proof sketch: Using prime factorizations, GCD takes minimum powers and LCM takes maximum powers. For each prime p with powers eₐ in a and eᵦ in b:

min(eₐ, eᵦ) + max(eₐ, eᵦ) = eₐ + eᵦ

So the product of GCD and LCM equals the product of a and b.

LCM Is Always ≥ max(a, b)

The LCM must be at least as large as each input.

lcm(5, 7) = 35 ≥ 7 lcm(4, 12) = 12 ≥ 12

Equality holds when one divides the other: lcm(4, 12) = 12.

When Numbers Are Coprime

If gcd(a, b) = 1, then lcm(a, b) = a × b.

lcm(5, 7) = 35 (since 5 and 7 share no common factors) lcm(8, 15) = 120 (since gcd(8, 15) = 1)

Coprime numbers have no overlap in their prime factorizations, so the LCM is just the product.

Adding Fractions

To add 1/4 + 1/6, find a common denominator.

The LCD (least common denominator) is lcm(4, 6) = 12.

1/4 = 3/12 1/6 = 2/12 1/4 + 1/6 = 5/12

Using the LCM keeps denominators small — 12 instead of 24 (the product).

Cycle Synchronization

Example: A stoplight cycle is 90 seconds. A train crossing signal is 120 seconds. Both start at noon. When do they align again?

lcm(90, 120) = ? gcd(90, 120) = 30 lcm(90, 120) = (90 × 120) / 30 = 360 seconds = 6 minutes

They align at 12:06, then 12:12, then 12:18, ...

Periodic Events

Cicadas of different species emerge after 13 or 17 years (both prime).

lcm(13, 17) = 221

They emerge together only every 221 years. The prime cycles minimize overlap — an evolutionary strategy to avoid predators that track periodic emergence.

Properties of LCM

Commutative: lcm(a, b) = lcm(b, a)

Associative: lcm(a, lcm(b, c)) = lcm(lcm(a, b), c)

lcm(a, 1) = a: 1 divides everything, so the LCM is just a.

lcm(a, a) = a: A number's LCM with itself is itself.

lcm(a, b) ≥ max(a, b): Always at least as big as the larger input.

lcm(a, b) × gcd(a, b) = a × b: The fundamental relationship.

Multiple Numbers

lcm(a, b, c) = lcm(lcm(a, b), c)

Compute pairwise and combine.

lcm(4, 6, 9): lcm(4, 6) = 12 lcm(12, 9) = 36

LCM vs GCD: Dual Perspectives

GCD: What do a and b share? (intersection of factors) LCM: What does it take to contain both a and b? (union of factors)

gcd extracts common structure. lcm builds the smallest structure containing both.

They're dual concepts, linked by: gcd × lcm = product.

The Core Insight

The LCM is the smallest number where two rhythms sync.

Every common multiple of a and b is a multiple of the LCM. The LCM is the "smallest common container" — the minimum effort to accommodate both cycle lengths.

When you add fractions, schedule repeating events, or ask "when will these align?", you're computing LCMs.

Part 6 of the Number Theory series.

Previous: Greatest Common Divisor: What Numbers Share Next: Modular Arithmetic: Clock Math and Remainders

Comments ()